Exit Memo: Office of Management and Budget

Shaun Donovan, Director | January 5, 2017

Introduction

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) plays a unique role working across the Federal Government to help departments implement the commitments and priorities of the President. We develop the President’s Budget to ensure that the Federal Government makes needed investments in economic growth, opportunity, and security, while staying on a sound financial path. We work to ensure that, through effective management, the Federal Government delivers the services that the American people expect in smarter, faster, and better ways. And we work to ensure that federal regulations protect the health, welfare, and safety of Americans and promote economic growth, job creation, competitiveness, and innovation.

Over the past eight years we’ve made remarkable progress in each of these areas. Since 2009, Federal deficits have fallen by about two-thirds as a share of the economy, even as we made important investments in economic growth and national security. We have improved our long-term budget outlook significantly as well – mainly due to a growing economy, policies that ensure that the highest-income taxpayers pay a fairer share, the winding down of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and dramatically slower growth in health care costs, thanks in part to the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

We have led the Administration’s successful efforts to leverage technology and innovation to produce a smarter, savvier, and more effective government for the American people. We have made important progress in modernizing and improving citizen-facing services, including by establishing the United States Digital Service. We have integrated best practices to reform the way we buy and operate information technology and other products and services. We have cut wasteful spending, saving taxpayers billions of dollars on Federal IT, real estate, contracting and other costs.

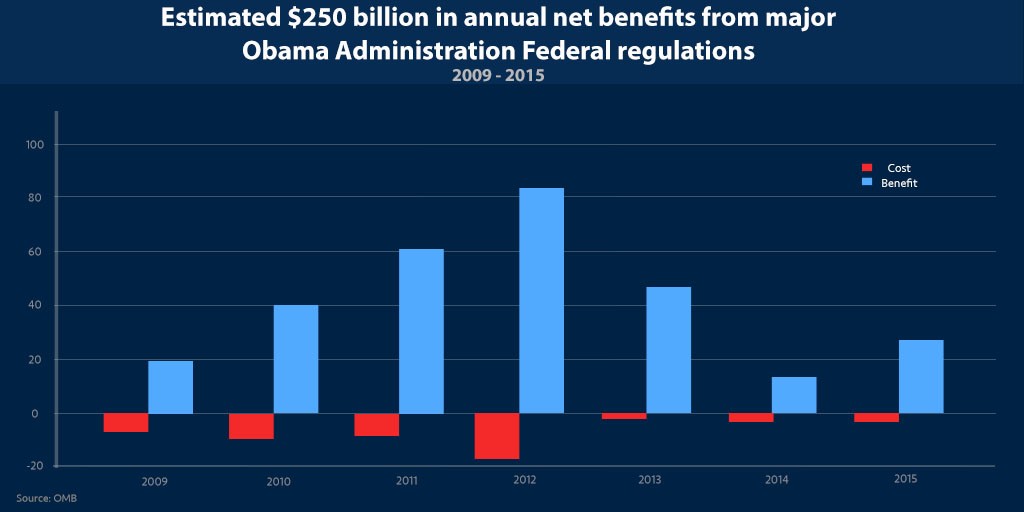

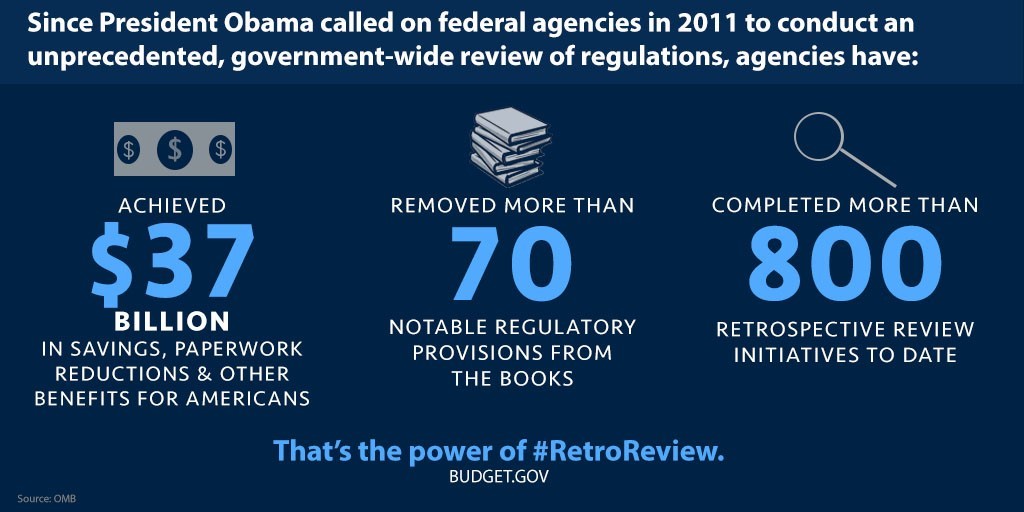

And we have led efforts to create a 21st century regulatory system – one that protects Americans and promotes economic growth. Major Federal regulations issued during the first seven years of this Administration have generated approximately $250 billion in annual net benefits, according to preliminary estimates. We also established and institutionalized a retrospective review process – an unprecedented, government-wide review of existing regulations – to create a more cost-effective, evidence-based regulatory system. Through this initiative, we have achieved an estimated $37 billion in cost savings, reduced paperwork, and produced other benefits for Americans over five years.

In this memo, I will lay out in more detail our accomplishments, as well as a vision for how we can continue our progress in the years ahead.

A Record of Economic Growth and Fiscal Progress

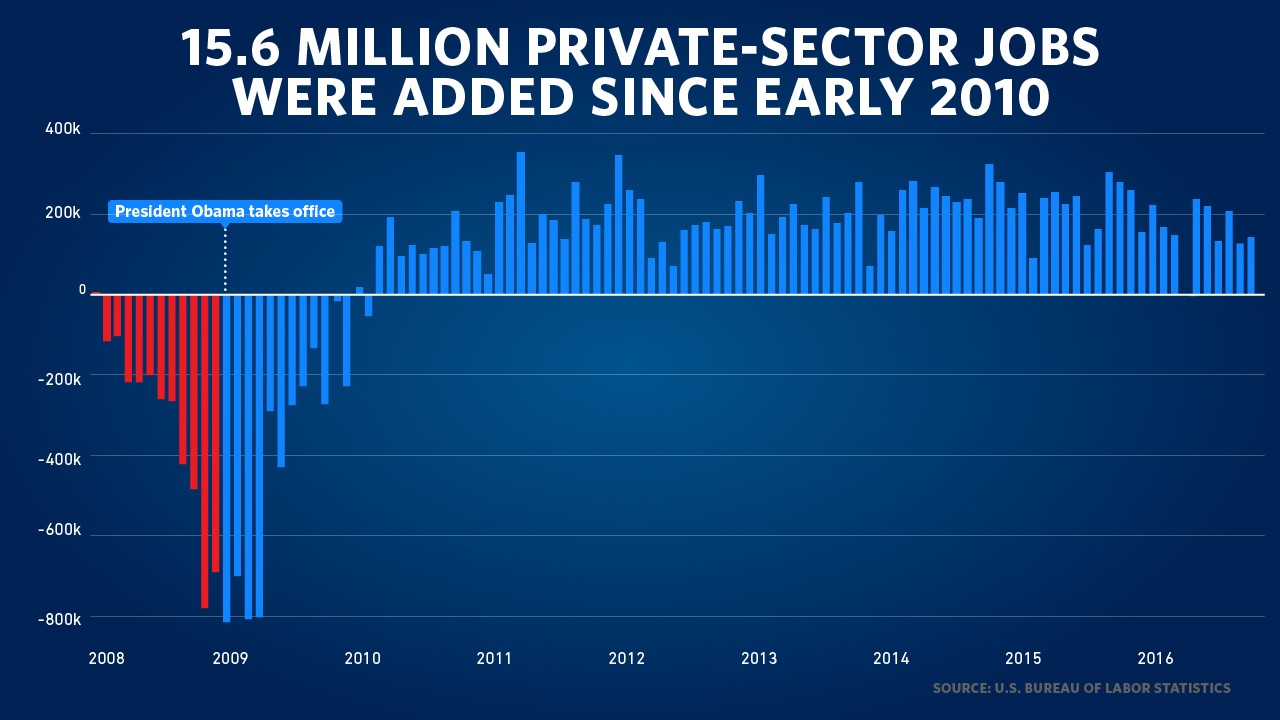

When President Obama took office in January 2009, the economy was shrinking at its fastest rate in over 50 years. Nearly 800,000 Americans lost their jobs in that month alone. But thanks to the President’s leadership, the resilience and hard work of the American people, and the decisive actions of policymakers, the U.S. economy has been an engine of job growth and economic expansion, outpacing other advanced economies in recovery from the Great Recession.

In total, American businesses have added 15.6 million new jobs since February 2010, including more than 800,000 new manufacturing jobs. The economy has experienced the longest streak of total job growth on record, adding jobs in 74 straight months. Since October 2009, the unemployment rate has been cut by more than half, falling to its lowest level in over nine years. Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has rebounded to more than 11 percent above its pre-crisis peak. In 2015, median household income rose at the fastest rate on record, with the largest gains going to middle- and working-class families.

The President, with the support of OMB and the entire Administration, made critical investments to spur this economic growth, including through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Recovery Act); the auto industry rescue; the Affordable Care Act (ACA); and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. At the same time, we succeeded in putting the Nation on a sound fiscal path. Since 2009, Federal deficits have fallen by about two-thirds as a share of the economy, and from 2009 to 2015, Federal deficits underwent the most rapid, sustained period of reduction since just after World War II. The President’s Fiscal Year (FY) 2017 Budget shows how we can continue to invest in our economic future and national security and address the country’s greatest challenges while further driving down deficits and reducing the debt over the next decade.

Our record of fiscal achievement extends to the medium- and long-term budget outlook, which have both improved significantly. Since 2010, our estimate of the 2020 deficit under current policies has come down by $521 billion, or more than one-third. Our estimate of the 25-year “fiscal gap” – the amount of deficit reduction needed to put the Nation’s finances on stable footing for the next 25 years – has also shrunk by a significant percentage.

Deficits during this Administration and projected future deficits have fallen due to three main factors: the economic growth described above; deficit reduction measures, including restoring Clinton-era tax rates on the highest-income Americans and winding down the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; and dramatically slower growth in health care costs, due in part to the health reforms contained in the ACA.

When President Obama took office, he immediately identified health care costs as one of the major drivers of the Nation’s long-term fiscal challenges, calling for health reform as “a step we must take if we hope to bring down our deficit in the years to come.” Since the ACA was signed into law in 2010, there has been significant progress toward providing all Americans with quality, affordable health care, including reducing the uninsured rate to its lowest level on record, as well as slowing health care cost growth.

In recent years, health spending has grown slowly in both private insurance and public programs. When adjusted for inflation and the number of enrollees, spending in Medicare has fallen over the past five years and spending on private insurance has grown at a small fraction of the average annual rate from 2000 to 2010. While some of the slow growth in health care costs in recent years can be attributed to the Great Recession and its aftermath, at least in the private sector, there is increasing evidence that much of it is the result of structural changes, including the reforms enacted in the ACA.

The health care cost slowdown is already yielding substantial fiscal dividends. Based on current budget estimates, projected Federal health care spending for 2020 has decreased by $224 billion, a reduction of 15 percent. These savings are above and beyond the deficit reduction directly attributed to the ACA when it was passed. In addition, since the 2009 trustees’ report, the insolvency date for Medicare’s Hospital Insurance Trust Fund has been pushed back 11 years, an improvement due in large part to Medicare payment reforms enacted in the ACA. These effects will grow as the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, which was created by the ACA, tests and scales up additional alternative payment models that incentivize quality and efficiency.

Continuing Our Nation’s Economic and Fiscal Progress in the Future

The President has led the country through a remarkable recovery from the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, established a foundation for stronger, more durable economic growth, and strengthened America’s long-term fiscal outlook. Still, more work remains to ensure that the economy works for everybody and that the Nation’s finances remain on a strong and sustainable path. Each of the President’s Budgets demonstrated that investments in growth and opportunity are compatible with, and necessary for, responsible fiscal progress. And I believe it is imperative that the next Administration and next Congress continue to prioritize investing in these areas in order to keep the economy thriving.

Eliminating the Threat of Harmful Sequestration Cuts. While discretionary spending restraint has played a role in deficit reduction, indiscriminate, harmful, automatic spending cuts known as “sequestration” – including sequestration cuts to date and projected sequestration cuts in 2018 and beyond – contribute only a small fraction to the improvement in the medium-term fiscal outlook described above. At the same time, sequestration has shortchanged investment in our economic health and national security. The American people continue to spur our economic and fiscal progress and it is critical that the Federal Government support, rather than impede, economic growth.

Sequestration was never intended to take effect: rather, it was supposed to threaten such drastic, arbitrary cuts to both defense and non-defense funding that policymakers would be motivated to come to the table and reduce the deficit through smart, balanced reforms. When that did not happen, instead of contributing to our fiscal health, the sequestration cuts that took effect in March 2013 reduced GDP by 0.6 percentage points and cost 750,000 jobs, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

Beyond the broader economic impacts, these sequestration cuts also had severe programmatic impacts, shortchanging investments that would have contributed to future growth, reducing economic opportunity, imposing unnecessary risk to our national security and harming vulnerable populations. For example, hundreds of important scientific projects went unfunded, with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding the lowest number of competitive research project grants in over a decade, limiting research into brain disorders, infectious disease, and cancer. The Department of Defense (DOD) furloughed about 650,000 civilian employees, and had to significantly curtail Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps training activities, which hurt their readiness to respond in the event of an emergency. Head Start enrollment dipped to its lowest level since 2001, with tens of thousands of low-income children losing access to Head Start and forgoing critical early learning experiences and health and nutrition services intended to help improve their cognitive, physical, and emotional development. Fewer low-income families received housing vouchers, with a total of 67,000 Housing Choice Vouchers lost, which reduced access to affordable, safe, and stable housing for low-income families.

Washington dysfunction impeded the hard work of the American people to grow the economy in other ways. Congressional Republicans shut down the Government for 16 days in October 2013, which resulted in economic disruption that the Council of Economic Advisors estimated to be up to $6 billion in lost output. Federal employee furloughs cost the taxpayers roughly $2 billion for work that wasn’t performed and a range of programs, from the National Parks to NIH research, were harmed. Following this failure to govern, policymakers recognized the need to move away from manufactured crises and austerity budgeting, helping to lay the groundwork for job market gains and stronger growth. The Administration worked with Congress to secure two consecutive bipartisan budget agreements (the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015) to alleviate harmful sequestration cuts, providing balanced sequestration relief for defense and non-defense priorities and replacing the savings with a smarter mix of revenues and spending reforms. The Council of Economic Advisers estimated that the 2013 budget deal would create about 350,000 jobs over the course of 2014 and 2015, so it likely made a significant contribution to the improvement in the labor market in those years. The 2015 agreement was expected to create an estimated 340,000 jobs in 2016 alone, while supporting middle-class families, investing in long-term growth, protecting Social Security, and safeguarding national security.

With sequestration projected to return in full in 2018, Congress will need to act again to finally and fully end sequestration. Doing so would avoid cuts that limit our ability to invest in the building blocks of long-term economic growth, like research and development, infrastructure, job training, and education, and that put our national security at unnecessary risk, not only through pressures on defense spending, but also through pressures on the Department of State, USAID, the Department of Homeland Security, and other non-defense programs that help keep us safe. I urge the next Administration and next Congress to take action to lift the ongoing specter of sequestration and ensure that our country is able to invest in our growth and security.

Health, Tax and Immigration Reform. To continue our progress, the President has called for strategic investments to grow our economy paired with smart reforms that address the true drivers of our long-term fiscal challenges, including an aging population, health care cost growth, and insufficient revenues to keep pace with these trends. The 2017 Budget includes significant health reforms that will help sustain the recent historic slowdown in health care cost growth while improving health care quality. It achieves significant deficit reduction from reducing tax benefits for high-income households, helping to bring in sufficient revenues to make vital investments while also helping to meet our promises to seniors. And it reflects the President’s support for commonsense, comprehensive immigration reform to fix our broken immigration system, which will boost economic growth, reduce deficits, and strengthen Social Security. The positive fiscal impact of these reforms grows over time and the next Administration should consider a similar path.

Addressing the Economic and Fiscal Risk of Climate Change. From the beginning of the Administration, the President recognized that climate change is not just an environmental challenge, but a pressing economic and fiscal threat. As with many of the challenges we face, a failure to act now will lead to greater costs and risks to our economy in the future. The impacts of climate change – like the interaction of severe storms and higher sea levels, higher temperatures and longer wildfire seasons – threaten to disrupt the Nation’s agriculture and ecosystems, water and food supplies, energy system, infrastructure, health and safety, and national security.

Through the Paris Agreement, we’ve set a goal of limiting global warming to well below two degrees Celsius. Meeting this goal could avoid damages equivalent to three percent of global annual output by 2100, relative to global warming of four degrees Celsius. In the United States, that could translate to more than $2 trillion in avoided damages each year in real terms by 2100 – the equivalent of nearly $350 billion per year in today's economy. The Federal balance sheet is also at stake. Without ambitious action on mitigation and adaptation, climate change is expected to reduce Federal revenue by hundreds of billions of dollars and increase Federal expenditures in areas like disaster relief, crop insurance, health care, and property management by tens of billions of dollars by the end of the century.

But, even as we have taken aggressive action to slow the change in our climate, the President has understood the need to adapt to the changes already taking place. That's why the Administration has led the Federal Government in integrating resilience into the fabric of how we build, rebuild, plan, and prepare for the impacts of climate change. We've been incorporating the best available science and data – including temperature and sea level rise projections – into planning and design. And we've been collaborating with a wide range of stakeholders – including State, tribal and local elected officials, business leaders, and science and policy experts – to maximize impact. To ensure communities are better prepared for the impacts of climate change today and tomorrow, the Administration has been investing in communities to ensure they don't just rebuild in the aftermath of a disaster, but rebuild smarter.

The next Administration should further invest in our Nation’s transition to a climate-smart economy that addresses the fiscal risks that climate change poses to businesses and governments alike. The President’s 2017 Budget includes significant investments in clean energy and other innovation that will help grow the economy and create jobs. It includes investments in a new, sustainable transportation system that will speed goods to market while reducing America’s reliance on oil, cut carbon pollution, and strengthen our resilience to the effects of the changing climate.

A Government of the Future

From his first days in office and with the creation of the first Chief Performance Officer of the U.S. Government, the President has prioritized improving how government works — by directing change that makes a significant, tangible, and positive difference in the economy and the lives of the American people. Over the past eight years through the President’s Management Agenda, OMB has led the Administration’s successful efforts to modernize and improve citizen-facing services, reform the way we buy and operate information technology in the 21st century, eliminate wasteful spending, reduce the Federal real property footprint, and help spur innovation in the private sector. This approach is working. This Administration has achieved nearly $4.7 billion in IT savings, saved more than $2 billion in Federal contracting, and decreased its real estate footprint by 25 million square feet.

This management agenda has four pillars: 1) Effectiveness—delivering a Government that works for citizens and businesses; 2) Efficiency—increasing quality and value in core operations; 3) Economic Growth— opening Government-funded data and research to the public to spur innovation, entrepreneurship, and job opportunities; and 4) People and Culture—unlocking the full potential of today’s Federal workforce and building the workforce we need for tomorrow, which is addressed in the memo of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). The Administration executed the President’s Management Agenda through Cross-Agency Priority (CAP) Goals, which were introduced by this Administration to improve coordination across multiple agencies to help drive performance on key priorities and issues.

Effectiveness: A Government that Works for Citizens and Businesses

President Obama has leveraged technology and innovation to produce a smarter, savvier, and more effective government for the American people. This Administration has introduced best practices from the public and private sectors and is using more modern technologies to break down traditional silos and make government operate more efficiently.

Modernizing IT and Strengthening Cybersecurity. Over the past eight years, OMB has focused on helping agencies modernize their IT infrastructure and strengthen their cybersecurity posture. Modernization is not simply replacing outdated IT systems with newer ones. It is a holistic approach that fundamentally transforms how agencies accomplish their missions. This topic is explored in further detail in the attached document – “Toward an Ever Better Digital Government” – which discusses the Administration’s approach to modernizing the use of technology and technical expertise in government, and provides a roadmap for the future. As this working paper notes, the U.S. Government is still in the early stages of this modernization effort.

Perhaps most critically, the Administration has taken aggressive action to enhance the government’s cybersecurity posture. Released in February 2016, the President’s Cybersecurity National Action Plan (CNAP) is the capstone of more than seven years of determined effort in this regard. It builds upon lessons learned from cybersecurity trends, threats, and intrusions that have occurred in recent years. Highlights of the CNAP include creating the first ever Federal Chief Information Security Officer and proposing a multiyear, multibillion dollar IT Modernization Fund. OMB also issued the first Cybersecurity Workforce Strategy, which enhances agencies’ ability to recruit and retain our cyber talent, and facilitated the hiring of more than 6,000 cyber employees in 2016, eclipsing 2015 by over 1,000 hires.

OMB also issued updated and revised OMB A-130 guidance for government-wide IT management, security, and privacy. The guidance had last been updated in 2000, prior to the advent of pervasive networked, social and mobile information technology. Under the new guidance, agencies are required to identify the expected lifespan of IT systems and to develop and implement plans to retire and upgrade IT systems with regularity. Agencies are required to ensure sufficient IT hardware and software visibility and asset management; to exercise comprehensive IT risk management; and to encrypt, by default, moderate- and high-impact data.

Modernization also requires agencies to reengineer underlying business processes and to increasingly migrate to more modern delivery models for IT and cybersecurity, such as cloud and shared services. Cloud-based IT delivery allows agencies to pay for only the resources and services they use without overhead costs. To realize these benefits, OMB issued the Federal Cloud Computing Strategy in 2011.

In 2010, OMB launched the Federal Data Center Consolidation Initiative (FDCCI) to reduce the number of Federal data centers and associated costs. Since that time, agencies have closed over 1,900 data centers and saved nearly $1 billion. However, the Federal government still operates more than 9,000 data centers. To address this, the Data Center Optimization Initiative requires agencies to consolidate their data center infrastructure and aims to reduce costs by $2.7 billion by the end of FY 2018.

The Administration also implemented numerous reform efforts to reduce IT duplication and improve outcomes. New data-driven reviews such as TechStats and PortfolioStats analyzed poor-performing IT investments as well as enterprise-wide IT management challenges. Combined, these programs helped the government achieve nearly $4.7 billion in savings.

The Administration has also engaged in a series of targeted initiatives to secure Federal networks and data. Through a series of policy efforts and initiatives civilian agencies increased their use of Personal Identity Verification (PIV) cards from 1 percent at the outset of the Administration to 85 percent today. OMB and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have worked with federal, civilian agencies to identify, assess, and secure their high value IT assets, which comprise unclassified information and IT systems that, if compromised, pose the highest risk to Federal Government operations and public trust. Lastly, DHS began implementing the Continuous Diagnostics and Mitigation (CDM) program to help agencies increase their ability to identify and manage assets on their networks and to detect vulnerabilities. These efforts ensure that agencies have the capabilities to safeguard their networks, systems, and data well into the future.

Delivering Digital Services to the Public. In 2014, the Administration launched the U.S. Digital Service (USDS) to help improve the performance and cost-effectiveness of the government’s most important public-facing digital services via the application of modern technology best practices. Over the last two years, USDS has executed hands-on technical engagements to improve outcomes on major agency projects, partnering with departmental personnel.

For example, we improved the ability for Veterans to apply for health care benefits online through a new digital application on vets.gov. USDS has worked with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to move from a highly troubled online application for health care (which subjected up to 70 percent of veterans to error messages that blocked them from applying for health care online) to an improved new online application that has resulted in an eight-fold increase in online applications, helping put VA on track to increase the percentage of Veterans applying online from 10 percent in 2015 to over 50 percent in 2017.

USDS has also helped modernize our country’s immigration system by digitizing the external application and internal review process for more than seven million annual immigration applications. Through the new my.USCIS.gov platform and Electronic Immigration System an increasing share of the immigration system is now online, including the green card renewal application (I-90), which has a 93 percent user satisfaction rate.

And, USDS worked with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to introduce Secure Access, a user verification process that provides taxpayers with convenient, secure access to their IRS information while protecting taxpayer information from automated fraudulent attacks.

In addition to building these important services, USDS has helped to create a pipeline for top technology talent from the private sector to participate in tours of duty with the Federal Government and partner with top civil servants to modernize some of our most critical public services and ensure a lasting culture of innovation that will serve the American people for years to come. More than 200 engineers, designers, data scientists, and product managers have answered the President’s call and signed on for a tour of duty with USDS. It is my hope that future Administrations will follow this model and bring top technical talent into government to ensure that we are best equipped to deliver modern services to the American people.

Protecting Privacy in the Digital Era. As more and more personal information is collected and shared in our digital economy, the Federal Government needs to ensure that its privacy practices evolve to appropriately reflect the Government’s use of emerging technologies, while also maintaining America’s position as a leader in innovation. To meet this challenge, OMB led a groundbreaking effort to enhance how Federal agencies protect the privacy of individuals and their information.

Key initiatives included the establishment of a Federal Privacy Council, the creation of a new privacy office in OMB, and the appointment of a Senior Advisor for Privacy. In addition, OMB directed agencies to evaluate the effectiveness of their privacy programs and designate a senior privacy official. In response, agencies across the Federal Government increased the resources dedicated to protecting privacy, revised policies and restructured their privacy programs, and appointed a new cadre of senior privacy officials. Finally, OMB published new guidance and spearheaded initiatives to improve how agencies prepare for and respond to breaches involving personal information.

Together, these efforts are designed to shift the focus of privacy programs away from a “check-the-box” compliance approach to a more strategic, continuous, and risk-based approach. This shift will help agencies make better decisions, use accurate and timely data more effectively, avoid risks, reduce costs, and improve the efficiency of government programs.

Transforming Federal-Local Partnerships. Across the country, citizens and local leaders are seeking a Federal Government that is more effective, responsive, and collaborative in addressing their needs and challenges. Far too often, the Federal Government has taken a “one-size-fits-all” approach to working with communities and left local leaders on their own to find Federal resources and navigate disparate programs. Responding to the call for change from local officials and leaders nationwide, OMB has worked across agencies to provide a more seamless process for communities – crossing agency and program silos and cutting red tape to support cities, towns, counties and tribes in implementing locally-developed plans for improvement. This work has been done through a Community Solutions team at OMB and through an interagency Community Solutions Task Force that have helped on projects from re-lighting city streets to breathing new life into half-empty rural main streets. We created new training opportunities to equip career officials with skills to identify local priorities, build local capacity, and use data to measure success, replicate what works, and make evidence-based investments. And we established communities of practice for peer-to-peer learning and innovation sharing in and across communities.

Building on this success, the President established a Council for Community Solutions to streamline and improve the way the Federal Government works with cities, counties, and communities – rural, tribal, urban and suburban – to improve outcomes. The Council includes leadership from agencies, departments, and offices across the Federal Government and the White House, who together will develop and implement policy that puts local priorities first, highlights successful solutions based on best practices, and streamlines Federal support for communities.

Efficiency: Increasing Quality and Value in Core Operations

Over the years, duplicative administrative functions and back-office services have made the Government less effective and wasted taxpayer dollars. Over the course of this Administration, OMB has worked to improve agencies’ core management activities through a focus on data-driven management to identify what works and what doesn’t work across government. By better leveraging the experience that exists within agencies to identify and share best practices, agencies can operate more effectively and efficiently within existing resources. The Administration has fostered the sharing of data across agencies for IT, acquisition, financial management, human capital, and real property.

Buying Smart. In 2014, the Administration launched category management government-wide, drawing on best practices in both the public and private sectors. It is an innovative approach that is shifting the Federal Government from managing purchases individually across thousands of procurement units to buying as one, in order to leverage the Government’s purchasing power. We advanced innovative and effective category management policies that streamline the more than $8 billion in annual spending for IT software, hardware, and mobile services and devices. As a result of these efforts, we have saved more than $2 billion in Federal contracting and are on track to save an additional $3.1 billion by the end of FY 2017. We have seen prices drop by as much as 50 percent since the release of the workstation policy in 2015. Forty-five percent of the $1.4 billion in spending for laptops and desktops are now approved best in class solutions; so far, we have already seen the number of duplicative contracts drop by 25 percent.

In 2015, we launched the first-ever Digital IT Acquisition Professional Training program with a curriculum based in principles of agile software design so that acquisition professionals could gain valuable hands-on experience applying modern IT procurement strategies. And we launched the TechFAR Hub, which provides agency personnel involved in the procurement process with practical tools and resources for applying industry best practices to digital service acquisitions. To support these and other innovations, agencies have designated acquisition innovation advocates who are helping the workforce test new and better contracting strategies that shorten delivery times, increase customer satisfaction, and improve value.

We have also made strides in increasing efficiency through the purchase of reusable and open source software. The Federal Government spends more than $6 billion each year on approximately 50,000 software transactions. To cut costs, OMB released the Federal Source Code Policy to mitigate wasteful spending associated with duplicative software acquisitions. Increasing the use of, contribution to, and publication of open source software also expands our transparency and promotes innovation.

Optimizing the Use of Federal Real Estate. In 2013, the Administration issued the “Freeze the Footprint” policy to freeze the Federal Government’s real estate footprint and restrict the growth of excess or underutilized properties. This was the first government-wide policy that required Federal agencies to dispose of existing property to support new property acquisitions, and was a major success. Through this policy and administrative authorities, agencies took significant and creative steps to manage their real estate inventories by freezing portfolio growth, measuring the cost and utilization of real property to support more efficient use, and identifying opportunities to reduce the portfolio through asset disposal. As a result of these efforts, between FY 2013 and FY 2015, the Government’s office and warehouse portfolio declined by 24.7 million square feet. Building on this success, in 2015 the Administration issued the National Strategy for the Efficient Use of Real Property and the Reduce the Footprint policy, which was the first time an Administration established a government-wide policy objective to reduce the size of the government’s real estate footprint. When fully implemented, this policy will reduce the government’s real property footprint by an additional 61 million square feet between FY 2016 and FY 2020.

Engaging Agency Leadership with Data. In 2015, the Administration launched annual FedStat reviews with major agencies, establishing data-informed discussions about agency-specific administrative management priorities at the Deputy Secretary level, and highlighting successful practices and identifying areas of risk and potential improvement. These data-driven reviews led to a number of tangible improvements and provide a useful tool by which to continually improve the effectiveness and efficiency of individual agencies and the Government as a whole. The Department of Justice’s (DOJ) FedStat, for instance, drove action to improve the agency’s financial management. The agency identified differences in finance performance across DOJ bureaus and diagnosed potential root causes to help improve performance.

Streamlining Infrastructure Permitting. Federal agencies have worked to expedite the review and permitting of major infrastructure projects, including bridges, transit, railways, waterways, roads, and renewable energy projects. For example, federal agencies completed the permitting and review for the Tappan Zee Bridge in 1.5 years for a process that would have taken three to five years. The Administration has also laid the groundwork for future progress, working with Congress to include reforms in Title 41 of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act). The Administration has taken aggressive efforts to implement these reforms, creating the Federal Infrastructure Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC) to better coordinate and streamline agency reviews, Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officers at each agency to ensure there is a central point of accountability for meeting established timelines, and the Permitting Dashboard so businesses, State and local governments, and the public can track major infrastructure projects as they go through the permitting process.

Economic Growth: Opening Government-Funded Data and Research to the Public to Spur Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Job Growth

The Administration has invested in efforts to open up Government-generated assets, including data and the results of federally funded research and development (R&D)—such as intellectual property and scientific knowledge—to the public. Through these efforts, the Government has empowered, and continues to empower, citizens and businesses to increase the return on our investment with innovation, job creation, and economic prosperity gained through their use of open Government data and research results.

Using Technology to Unleash the Power of Data. On his first full day in office, President Obama issued the “Transparency and Open Government” memorandum, making clear that his Administration was “committed to creating an unprecedented level of openness,” and fostering a sense of transparency, public participation, and collaboration amongst the government and the American people. Since 2009, the Administration has made significant progress publishing biennial open government plans that include efforts to open up data sets that have never before been public. Today, nearly 200,000 datasets are available for free on Data.gov. Because of this foundation of open data, students are able to compare the cost of college with other information, such as graduation rates and average salaries of graduates to determine where to get the most bang for their buck. Communities can map demographic, income, and school data to promote Fair Housing. And patients can find information on the safety and cost of hospitals, nursing homes, and physicians, empowering them to make smarter health care choices.

Pursuing Evidence-Based Policy. The President has made it clear that policy decisions should be driven by evidence so that the Federal Government can do more of what works and less of what does not. There has been growing momentum for evidence-based approaches at all levels of government, as well as among nonprofits, foundations, faith-based institutions, and community-based organizations. The Administration’s embrace of these approaches has resulted in important gains in areas ranging from reducing veterans' homelessness, which is down by nearly 50 percent since 2010, to improving educational outcomes and enhancing the effectiveness of international development programs. We have helped to drive notable advances in the use of evidence in the Federal Government, including advances in innovative federal grant-making through “tiered-evidence” and “innovation fund” designs that focus resources on practices with strong evidence, while also supporting and evaluating promising practices so that we can learn what works best in different conditions.

For example, the Department of Education’s Investing in Innovation Fund – or i3 – provided funding to test new approaches to improving student outcomes and scale up approaches that already have an evidence base behind them. Larger grants were available for projects that were scaling up evidence-based practice while smaller grants were available to test new ideas. The i3 program funded more than 140 projects and is helping to uncover successful interventions in the areas of teacher and principal effectiveness, turning around low-performing schools, and implementing college-and-career-ready standards. The recently enacted Every Student Succeeds Act created the Education Innovation and Research Program, the successor to i3, and continued this focus on building evidence for what leads to better educational outcomes.

Continuing Our Progress Toward a Modern Government

While much has been accomplished, much works remains to modernize the management and operations of the Federal Government and better serve the American people. Below are a number of areas where I would encourage the next Administration and the next Congress to focus their attention in order to build on the critical progress we have made over the past eight years.

Maturing Agencies’ IT Management Practices. The Federal IT Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) was enacted in December 2014 as a mechanism to strengthen the role of agency CIOs and ensure greater accountability for the delivery of IT capabilities. Since then, agencies have made progress in improving their management practices and applying OMB’s implementation guidance. However, implementation has been uneven across the government and additional work remains. Efforts should focus on the necessary cultural and organizational changes required, particularly increased collaboration among agency leadership for IT management and delivery.

Strengthening Cybersecurity, Including through Further IT Modernization. Investments in strengthening our cybersecurity are critically needed, including in areas such as securing Federal information technology systems, protecting critical infrastructure, and investing in our cybersecurity workforce. For example, the President proposed $746 million for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to lead implementation of the Continuous Diagnostic & Mitigation program to assist agencies in managing cybersecurity risks on a near real-time basis as well as the $3.1 billion Information Technology Modernization Fund (ITMF), which will enable the retirement, replacement, and modernization of legacy IT that is difficult to secure and expensive to maintain. Congress recognized the importance of innovative new approaches to addressing our IT and cybersecurity needs, and the House introduced and passed by voice vote bi-partisan legislation authorizing the ITMF. In addition, the bipartisan Commission on Enhancing National Cybersecurity endorsed this approach and called for building on it by aggressively tackling the challenge of long-term planning to modernize our IT systems. However, Congress has not yet funded this proposal, and I encourage the next Administration and Congress to take action on this proposal without delay.

Continuing to Transform Critical Services through Technology Tools and Cultivation of Tech Talent. The USDS model has been validated over the last two years, as the Federal Government has delivered on providing better citizen-centered services and helping Americans engage with their government in new and meaningful ways. The pipeline for bringing top technology talent from the private sector to participate in tours of duty with the Federal Government and partner with top civil servants is strong. Maintaining a firm focus on citizen-centered projects and talent pipeline – including investing in current government employees – will ensure a lasting culture of innovation that will continue to serve the American people for years to come.

In addition, tech-savvy senior leadership has become fundamental to the success of government agencies (and, indeed, virtually all major institutions) in the 21st century. An agency which does not have individuals with high technical aptitudes on its core senior leadership team – and involved in policy and program formulation and execution at each step – will experience increasingly difficult problems and underachieve on its mission as time goes on. In today’s world, technology is a key strategic part of formulating policy and action in every field. It has become as essential to have technologists in the room as it is to have legal counsel. Accordingly, the next Administration should place a premium on recruiting, hiring, and developing the best technology talent in the country and making sure their advice informs public policy and government management.

Fully Implementing a Modern Acquisition Strategy. The move to utilizing category management government-wide and buying as one has been firmly established. The opportunity to fully leverage the Government’s purchasing power has become a reality. Moving forward, it is critical that the next Administration invest in the infrastructure to support and deepen category management to ensure that it becomes a permanent approach to buying common goods and services.

Improving Data Management. The vast amount of data that agencies collect and protect requires a careful approach to ensure appropriate resources are devoted to protecting those systems. Unfortunately, the lack of coordination among agency personnel who handle datasets throughout the information life cycle can lead to costly inaccuracies, unnecessary delays in making data available, and incomplete documentation. To help agencies think through how to identify and protect systems deemed of particular interest to potential adversaries, OMB asked agencies to submit information on their high value assets (HVAs) as part of the Cybersecurity Sprint. In addition, OMB directs agencies to define agency-wide data governance policies that integrate data management policies and roles. Data governance supports data quality and interoperability at each level of agency organizations. Further guidance informing agency data governance policies, as well as support for interagency coordination of data governance strategies, will further integration of data management priorities with agency missions.

Furthering the Use of Evidence in Making Policy Decisions. The President’s 2017 Budget includes many proposals that would continue to advance evidence-based policymaking by developing more evidence about what works, investing in the systems that will make it easier to learn and do what works in the future, and taking additional evidence-based approaches to scale. Building on these successes, this past year Congress unanimously passed and the President signed into law the bipartisan Evidence-Based Policymaking Commission Act of 2016, which created a 15-member Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking charged with examining all aspects of how to increase the availability and use of government data to build evidence and inform program design, while protecting the privacy and confidentiality of those data. The Commission has the opportunity to highlight and further the advances in evidence-based policymaking achieved during this Administration, including making better use of data already collected by government agencies and strengthening agency capacity to build evidence and communicate what works. The Commission could also play a key role in recommending to Congress and the next Administration the resources and structures needed to make critical capacity improvements and conduct rigorous evaluations in order to improve federal policies and programs.

A Regulatory System That Protects Americans and Promotes Growth and Innovation

Regulations help American families every day by saving lives, preventing illness and injury, and protecting consumers. Since the start of the Administration, the President has been committed to a 21st century regulatory system – one that maintains a balance between protecting the health, welfare, and safety of Americans and promoting economic growth, job creation, competitiveness, and innovation. Through the work of OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), our goal for the past eight years has been to maximize the effectiveness and benefit of the rules issued by Federal agencies and improve outcomes for the American public.

Regulations that Benefit the American People

The best measure of whether these regulations help the American people is whether they lead to an increase in the net benefits to society, including health and environmental benefits to the American people, as well as concrete and significant savings such as at the gas pump and in electric bills.

OMB strives to ensure that the costs of new regulations are justified by the benefits, a longstanding metric that has been respected across administrations. And we have done just that over the past eight years. The annual net benefits of major Federal regulations issued during the first seven years of this Administration are approximately $250 billion, according to preliminary estimates. We expect the estimated net benefits will be significantly higher once the totals for the end of the Administration are tallied. And we expect the net benefits of this Administration to meet or exceed those of the previous two Administrations.

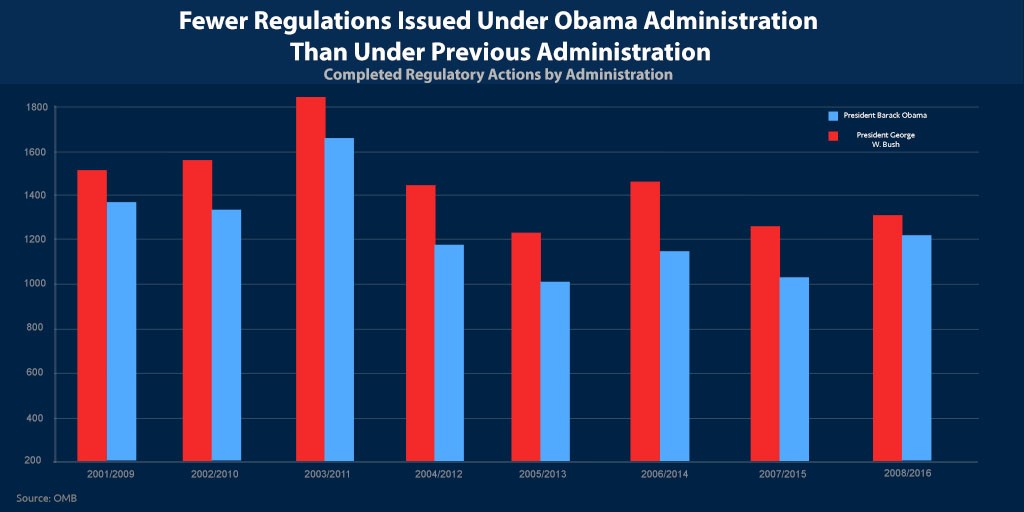

By several measures, this Administration has seen a significant decrease in the number of regulations issued. The Obama Administration has issued 16 percent fewer final rules than the previous Administration. In addition, the number of significant regulations, or those more notable regulations that met the threshold for OMB review, also decreased over the past eight years, compared to the previous Administration.

Reviewing and Revising Regulations to Adapt to a Changing World

The President also challenged the Federal government to establish and institutionalize a retrospective review process – an unprecedented, government-wide review of existing regulations that was launched in 2011 to create a more cost-effective, evidence-based regulatory system for the 21st century. This initiative is a hallmark of this Administration’s commitment to a transparent and accountable regulatory process. Its requirement for bi-annual, public updates of agency progress on retrospective review allowed for public participation and identification of areas where regulations were overly burdensome.

From maximizing savings and reducing burdens for State and local governments and industry, to eliminating tens of millions of hours of paperwork burden for our nation’s citizens and businesses, to removing duplicative and burdensome regulatory provisions from the books altogether, this Administration has made more progress on retrospective review and achieved more cost savings than any prior Administration.

To date, the retrospective review initiative has achieved an estimated $37 billion in cost savings, reduced paperwork, and produced other benefits for Americans over five years. As of July 2016, agencies had completed more than 800 retrospective review initiatives. While a key aspect of retrospective review is to review and revise regulations to better adapt to a dynamic world of evolving technology and changing circumstances, the President has directed agencies to go beyond this and eliminate rules or provisions of rules that are unnecessary. In fact, to date, agencies have removed more than 70 notable regulatory provisions from the books.

This effort has driven down costs for the American consumer. For example:

- The Environmental Protection Agency eliminated part of a 40-year-old rule that required some dairy farmers to prove that they could contain a milk spill – because milk had been classified as an oil because it contains animal fat. By exempting milk and milk product containers from the Oil Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) program, the EPA helped milk and dairy industries save an estimated $800 million over five years, which, in turn, can help reduce costs for consumers.

- The Environmental Protection Agency also eliminated an obligation on many states to require local gas stations in areas with moderate ozone pollution to install plastic sleeves over gas pump nozzles and other associated equipment, also known as an air pollution vapor recovery system. This measure was imposed in 1990, before vehicles were required to have built-in vapor recovery technologies. Once the vehicle vapor recovery technology became widespread, EPA finalized a rule eliminating the longstanding requirement for this now redundant technology. The anticipated five-year savings from this reform are estimated at $270 million.

- The Department of Labor worked to harmonize its chemical hazards warning requirements with those of other nations in 2012. This provided a common and coherent approach to classifying chemicals and communicating hazard information on labels and safety data sheets, helping to reduce trade barriers and saving employers more than an estimated $3 billion over five years.

- The Department of Transportation rescinded a requirement that commercial motor vehicle drivers operating in interstate commerce submit, and motor carriers retain, driver-vehicle inspection reports when the driver has neither found nor been made aware of any vehicle defects or deficiencies. The final rule, issued in 2015, is projected to save over 40 million hours in paperwork burden per year, for approximately $8.9 billion in savings over five years.

- And in December of 2016, the Federal Aviation Administration released a rule promoting increased flexibility in the airline certification process. This rule also promotes regulatory cooperation and design with our European, Canadian and Brazilian airline partners. This harmonization should lower costs for airplane and engine manufacturers with estimated benefits of $27.8 million.

The progress to date makes a strong case for the benefits of an ongoing, thoughtful review of regulations already on the books. Each dollar saved, each paperwork burden hour reduced, and each retrospective review initiative conducted means bigger savings, greater efficiencies, and a more effective government for the American people. We worked hard to institutionalize this proven and effective practice, including requesting that agencies submit reports in January 2017. I encourage the next Administration to continue this effort, pursuing a thoughtful and data-driven approach to assessing regulations that are currently on the books.

Closing Statement

It has been an incredible honor to serve President Obama and the American people for the past eight years, both as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development and as OMB Director. In more than two years at OMB, I have been privileged to lead an institution that makes a difference on so many issues that touch the lives of millions of Americans every day – to develop economic and budget proposals that create jobs and opportunity and protect our national security; to build a Federal Government that more effectively delivers the services that Americans rely on; and to put in place regulations that keep Americans healthy and safe while promoting economic growth and innovation. I have also been deeply inspired by the talent, expertise, and commitment to public service of OMB’s career employees. I am proud of what we have accomplished together and grateful for their continued service to our great country.

Attachment

TOWARD AN EVER BETTER DIGITAL GOVERNMENT

Executive Summary

Over the course of the last decade, Federal agencies have developed and operationalized many examples of using the power of modern digital technology to make government more efficient, produce better outcomes for citizens, and to make government data more accessible. At the same time, it is important to understand that the U.S. Government is still in the early stages of transitioning from aging legacy applications and infrastructure and deeply-entrenched legacy modes of software development and operation to modern technology and approaches – a shift to the true “digitalization” of government services that is in many ways literally unprecedented in the annals of technology, given the sheer size, scope, and complexity of the government and the extraordinary depth of the issues it must confront. The purpose of this working paper is to aid discussion and action on the path forward for this work, leveraging considerable, hard-won learnings to date, and to outline specific actions which can be taken going forward to continue to accelerate the transition to ever more effective use of information technology and the delivery of digital services by the Federal Government, namely:

- Continuing to recruit and hire a critical mass of high “tech IQ” (“TQ” – modern technological intelligence, expertise, and experience) senior executives for government agencies

- Continuing to build the capabilities of the United States Digital Service (USDS) and the General Service Administration’s Technology Transformation Service (TTS) as drivers of change

- Continuing to aggressively advance tech procurement reform and hiring/workforce reform

- Continuing to change governance, budgeting, financing, monitoring, and policymaking practices to most effectively support continuous modernization.

In the sense that this paper articulates a current vision for the future and how to move forward, it will always be a draft – it will continue to evolve as the U.S. Government keeps making progress, as technology continues to advance, and as government keeps learning more about how it can get better at leveraging technology to serve the American people.

The U.S. Government’s Challenge and Opportunity (Circa 2016)

The U.S. Government, like many long-established large enterprises, is currently going through the early and often chaotic phases of digitalizing its processes, including how it interacts with other players in its ecosystem (citizens, businesses, other government institutions, etc.). For purposes of this discussion, “digitalization” is purposely and deliberately differentiated from “automation,” a process which has been underway for decades.

“Automation” can be characterized as the use of information technology to speed up existing business processes and interactions, and often can bring significant computing power to assist in performing tasks which would otherwise require excessive amounts of labor and resources. Examples of automation include payroll processing, performing bookkeeping and financial calculations, and even first and second generation web forms that largely mirror the paper forms and business practices upon which they were originally based. Close examination of business processes that have been “automated” often reveals very little real process change from their manual/analog counterparts, other than the addition of speed or reduced labor costs. In many organizations, the concept of “workflow automation” is tacit recognition that we are using the same business processes as before.

Digitalization is fundamentally different from automation in that one of its core characteristics is the focus on continually using the customer/user experience to guide the design of an information system. Historically, the design orientation of information systems has been around a business task to be completed from an internal business viewpoint, and not on customers’ expressed or implied needs, and certainly not based on an understanding of customer/user preferences, as well as the customer/user context (e.g., location, prior activity, relationships, etc.).

The digital approach to building technology puts users at the center of the design process. This makes developing a product like crossing an ocean using a homing beacon – you get constant user feedback that allows you to adapt and stay on target as you go. Without that feedback, you have no way of learning as you go (this is known as “dead reckoning” in navigation). Even if you’re brilliant at setting off in the right direction, you usually end up missing the mark and wasting a lot of effort along the way. You’re stuck with whatever your initial direction was because you don’t have any guidance to allow you to know how to adapt. (It’s even worse in the case of software because the user often can’t describe what they really need, so the target can move around – unlike islands).

This user-as-homing-beacon approach is at the heart of digitalization, whereas most government software has historically been developed using the dead-reckoning approach that’s at the heart of automation. This difference is a key driver of why a digital approach is able to get both tremendous efficiency improvements and significantly better outcomes. It requires two things – a homing beacon (i.e., a desired outcome with continual user feedback instead of a predetermined set of specifications) and the ability to adjust course based on that feedback (i.e., processes that have the agility to be able to continuously adapt).

One of the most significant signs that an enterprise is not “digital” in its thinking and its approach to serving customers is to compare the architecture of its information systems to the organization chart of that same enterprise. If, as is the case with most of the information systems in the Federal Government, there is a 1:1 match, it is highly likely that customers are not being well served. This “organizational chart”-bound paradigm for managing information is a symptom that there may be numerous factors which will need to be addressed in order to make a digital transformation work. These could include issues of governance, funding model limitations, procurement practices, workforce structure and skill sets, organizational culture, and legal and regulatory constraints, as well as the adoption and use of modern technology.

Quite often, digitalization harnesses newer and more boundary-free forms of technology (such as mobile, internet-connected sensors, social media, metadata, cloud services, etc.) to deliver a differentiated and personalized end-user experience. In the new digitalized world, machine learning can be leveraged to provide a uniquely personal customer/user experience, delivered by a flexible and scalable set of standardized tools, applications, and infrastructure.

Top digitalized enterprises also eschew monolithic systems for modular ones. A system made of small modular, reusable, shareable components is much more agile and flexible than the traditional monolithic system. Modular building blocks can be rearranged easily, whereas it’s very hard and expensive to make significant changes to a large monolithic structure, like a large traditional custom software system. And modules interlock easily so when someone builds or procures a new one, it can be used in other systems.

Successful digitalized enterprises also don’t build/repetitively rebuild what they don’t need to build/rebuild. Rather than writing functionality from scratch, a software and IT team can utilize already extant cloud APIs and services together to build and deliver much of an application’s functionality. In the private sector, this has resulted in a huge improvement in productivity over the past few years for development teams leveraging these modern approaches. A growing fraction of cloud services can be securely and cost-effectively provided by external third-party providers. Those that must be built internally can be made available across the enterprise for reuse as modular building blocks in multiple systems.

Digitalization of an enterprise also requires a change in the way that the enterprise thinks about the businesses and the activities it is engaged in, and the way it organizes and staffs its projects and recruits talent, and in the way that it designs, develops, operates, and supports new and existing products and services. While there are technology implications that will require attention, business processes in the government will require a major overhaul in order to deliver on the digital opportunity.

Well-known private sector examples of the digital transformation in thinking and design include Amazon’s journey (it was an on-line retailer of books, and now is a global digital marketplace and cloud services provider) and Netflix (which was a subscription consumer DVD delivery service, and now is a premium streaming digital content provider and digital content producer). One of the lessons learned from both of these digitalization examples is that while both of these are relatively new companies, each of them underwent a radical transformation in terms of their relationships with their customers, and in the way they developed products, generated revenue, and in the way they managed the underlying information technology environment to deliver these capabilities.

The Challenge

With the understanding that departments and agencies will be operating in a bi-modal environment (i.e., running the old stuff while building out the new) for the foreseeable future, the problem government faces today is how to accelerate the migration from legacy business processes, applications, infrastructure, and organization toward a modern, digitally empowered end state that is capable of more efficiently and effectively delivering services to the American people and supporting the functions of the Federal Government – a state that views IT not as a series of automation projects that must be developed and then maintained, but rather as an enabler of digitalized customer-oriented services that are continuously refreshed and incrementally improved.

The modes via which the Federal Government has historically procured and developed information technology and digital services have lagged significantly behind private sector best practices. At the core, the Federal Government has had to grapple with historical issues which can be summarized as follows:

- Outdated, inflexible approaches to software procurement, development, operations and funding that are deeply wired into government processes, practices, and customs

- Lack of customer-centric design. Agencies and their components are highly mission-driven, and therefore so are their information technology "architectures" and "designs" as well as their underlying data sets and operating processes. Agency information systems often have the general design characteristic of "inside->out", meaning that they have mostly been engineered from an internal perspective to capture and process information that an agency needs to carry out its mission. Few are designed with "self-service" in mind, and those that do are likely a "one-size fits all" model with little to no personalization or customer-centric design incorporated into the application. Furthermore, many agencies and agency components are unfamiliar with modern, user-centric design practices, and face significant internal barriers to the kind of unfettered user interactions, rapidly iterative “A/B testing” approaches, and other practices that are fundamental to the creation of modern digital service experiences.

- Outdated “waterfall”-style approaches to software procurement and development and lack of system adaptability. Historical government agency processes, management practices, customs, and compliance infrastructure are deeply wired to support outmoded “waterfall”-style software development, characterized by extensive upfront gathering of detailed requirements and rigid, inflexible, multi-year solution specification, funding, procurement, and development of monolithic software to fulfill those requirements.

- Custom-developed “hard-wired” solutions and interfaces. Systems and underlying infrastructure have grown incrementally and substantially over time in the form of highly customized software, and default to the addition of complex interfaces as new agency mission requirements are added or mission objectives change. Custom one-off interfaces have become the norm, and these are especially vulnerable to change-induced errors on either end of the custom interface.

- Difficulty upgrading or replacing legacy applications and infrastructure. Most of the existing Federal information technology environment exists in a "wait ‘til it breaks" model in terms of upgrades or replacement from an agency priority and funding perspective. Reinforcing this in many cases are rigid vendor contracts; agencies who are not regularly replacing and upgrading their technology environments are getting “locked in” to paying high maintenance costs for underperforming and inefficient automation-focused hardware, software, and infrastructure. Across the Federal Government, agencies report that they spend an average of roughly 80% of their IT funding on what is referred to as “O&M” (operations and maintenance) expenses. Agencies often miss benefits of industry innovation, which has seen computing power double every 18 months or so for the same cost, and where storage and networking costs continue a race to the bottom.

- Inflexible federal budgeting and appropriation processes. Federal budgeting and appropriations processes for IT expenditures have been generally based on a model which makes securing funding for the costs of operating and maintaining the status quo relatively routine vs. the process for obtaining funding for replacement or upgrades. Even when there is a strong desire and a compelling argument to upgrade or replace applications or infrastructure, the “bubble” cost of operating the old while building the new has often been outside the parameters of the existing budgeting culture and practice.

- Rigid set of procurement practices. Rigid contracts often lack built-in incentives for suppliers to upgrade or replace outdated applications and infrastructure and can hinder the government’s ability to make incremental changes as well as leverage current private sector innovation. This, along with the prevalence of outdated, inflexible practices as described above, plus a lack of agency acquisition expertise deeply versed in modern digital service contracting best practices, make it difficult for agencies to leverage cloud service consumption models and easily purchase modern software design and development services in a timely and effective way.

- Lack of modern tech management and contractor “firepower”

- Paucity of modern technical engineering, product management, and design talent. The skills required to manage, procure and execute the creation of effective next-generation digital services are different from those required to automate existing business practices, and these skills are rare in existing Federal IT organizations. The recruiting and hiring process these organizations depend upon generally has not adequately attracted and selected individuals with these specialized skills. Furthermore, use of rapid training boot-camps, apprenticeships and other new methods for upgrading the basic skills and approaches of talent already in government are only available in a tiny number of agencies. As an important point: the need is not for the Federal Government to hire all of its own engineers, product managers and designers. The vast majority of government digital service development work should continue to be done by private sector contractors, as is true today. However, government needs a certain critical mass of top-flight in-house technical talent in order to be a good buyer of private sector services – otherwise, government will do a poor job of specifying the solutions it truly needs, won’t be able to evaluate accurately which contractors are the best ones to deliver those solutions, will manage contractors badly, and won’t be able to drive continuous iteration of how agencies work to support execution of the latest best practices (e.g., today, moving agencies from “waterfall” to agile development, from monolithic systems to modular systems, from repetitive rebuilding of services to reuse of services, including extant, commercially available, cloud-based services).

- Paucity of innovative new vendor entrants into the government marketplace. A profusion of barriers to entry into the government marketplace that have accumulated over the years has resulted in a multitude of innovative, modern vendor options that are available to commercial enterprises being inaccessible to government agencies. Furthermore, the prevalence of outdated digital service development and management practices across government, articulated above, has discouraged modern vendors from working with government – as these practices would render those vendors unable to execute and operate in accordance with their core norms (e.g., unable to execute truly user-centered, agile design and development; unable to leverage cloud-based services; forced to comply with an obsolete technical reference architecture and archaic reporting and management requirements; etc.).

- Need for much stronger sponsorship and involvement by senior agency leadership. In the rare instances that money is obtained for either new programs or upgrade and replacement of existing applications or infrastructure, agencies often receive the funding as a one-time “grant” or appropriation, and once obtained, have often considered these as “IT projects,” when they in fact need to be treated as large-scale, extremely difficult agency change management projects that require much more active sponsorship and involvement by top agency leadership than they have often historically gotten. Absence of strong change management leadership from senior agency leaders can lead to poor program performance and irrationally-shifting requirements and priorities over the lifetime of an effort.

- Collaboration challenges

- An “organization chart”-oriented paradigm for the funding, design, delivery and operation of IT capabilities. Each agency (and in many cases, each of its sub-components) has been individually responsible for designing, developing, operating, and securing nearly 100% of its information technology capabilities. This includes core business applications, productivity suites, local and wide area network capacity and capability, data centers, and web services. There are a few examples of services that are shared between agencies within the Federal enterprise, such as payroll, ERP, and accounting, data center hosting, Einstein, and CDM. However, these examples represent a fraction of the total investment in information technology, and similarly, a small fraction of the total capability of the Federal enterprise. In comparison to a modern digitalized enterprise, the Federal Government is only just beginning to experiment with shared digital services.

- Lack of modern productivity and collaboration tools that work across government silos. This hinders the ability to interoperate with other agencies and to securely support mobile and remote work. Further, execution speed is hindered by the lack of these tools; Federal employees could work far more rapidly together to make progress on transformation work --- as well as work on any other topic -- if they had modern collaboration tools both within their agency and especially cross-agency.

The Opportunity

The “digitalization” of the Federal Government requires applying new modes of management and operation, new kinds of skills and expertise, and strong sponsorship and support from senior leadership to overcome these challenges. It is a shift that requires government to embrace secure and reliable cloud services, customer-centered design, agile development, shared services, a "continuous upgrade" model of technology refresh and replacement, and enhanced cybersecurity while retaining the ability of agencies to focus on their mission goals and objectives. It is a shift that requires government to alter its focus from completing technology “projects” to instead focus on delivering effective, continually improving services. Most fundamentally, it is a shift that requires government to build up its ability to keep evolving as technology evolves; the transformation of government for the better is a continuous, iterative journey, not a destination.

Specifically, this approach has the following characteristics:

- Guided by leadership with deep experience and expertise in modern technology and business process redesign, and excellent, situation-specific technical judgment, the Federal Government significantly expands (a) the use of secure, scalable, reliable and appropriate cloud-based services (public, private/government, and hybrid) and (b) the development/use of shared government services (e.g., identity management) where optimal -- services which utilize modern technology and consumption models and are significantly more secure, more efficient, more scalable, more reliable, and less costly than what agencies might individually attempt to build on their own.

- Government expands its use of commercially available cloud-based services, giving it the agility to scale resources up or back, and also tapping into the firepower of the private sector in which teams of highly capable minds are concentrated on a service’s particular specific functional area, backed by significant financial resources and guided by feedback from a large customer base.

- Well-made solutions to common problems are easily shared across the government, in the form of APIs, source code, infrastructure, and fee-for-service offerings.

- Agency and component information technology efforts are able to execute much faster and are increasingly focused on those unique capabilities that are highly and uniquely mission-aligned.

- Critically, at a molecular level, and informed by best practices in public and private organizations, ongoing transformation is driven by small teams who are deeply experienced in modern technology and working in modern ways, who benefit from strong support for transformation from management, and who are empowered to quickly make decisions relevant to their digitalization efforts.

- These teams may be focused on development of new services, revamp of existing services, acquisition and integration of commercial products and services, or a combination of these actions in service of a particular mission. The teams are cross-functional, including both experienced technical talent and other subject matter experts. They are empowered by senior leadership to challenge the status quo and drive changes how agencies procure, develop, operate, and manage digital services in accordance with current best practices and what is best for the mission at hand. Missions of larger scope are handled not by larger teams, but by federations of small teams working together in coordinated fashion.

- Teams are able to procure (a) private sector contractors deeply experienced in modern, best-practice digital service development and (b) top-performing commercial service and product offerings from a highly competitive government marketplace in a timely, effective, and efficient way. Private sector contractors will continue to execute the vast majority of government digital service development work; and commercial service offerings, such as cloud-based services that already exist and don’t need to be replicated by government but can instead be leveraged by government, will be increasingly vital to government’s future success. It is critical that government have access to the best and most innovative offerings in these spaces. Teams are also empowered to drive adoption and integration of open source software, and leverage government shared services and APIs that solve common problems across the Federal Government, such as identity management and security services.

- Teams are both responsible and accountable for the delivery of the mission. They are responsible for creating, gaining agreement on, and reporting on metrics of success for their mission area with clear expectations of performance, security, scalability and reliability for customers.

- In the realm of digital service development in particular, teams have expertise working in the mode of the Digital Services Playbook[1], whose proven core principles for digital service development (circa December 2016) are:

- Understand what people need

- Address the whole experience, from start to finish

- Make it simple and intuitive

- Build the service using agile and iterative practices

- Structure budgets and contracts to support delivery

- Assign one leader and hold that person accountable

- Bring in diverse, experienced teams

- Choose a modern technology stack