Strengthen Efforts to Prevent Drug Use in Our Communities

Principle 4. Criminal Justice Agencies and Prevention Agencies Must Collaborate

Law enforcement agencies are critical partners in community-based prevention strategies and can help reduce youth involvement in drug-related criminal activity. Some communities have begun to employ effective collaboration among police, prosecutors, judges, probation officers, corrections officials, and their counterparts in the prevention field. For example, PACT360 (Police and Communities Together) is a community education program funded by DOJ and implemented in collaboration with the Partnership at Drugfree.org. In FY 2010, DOJ awarded two new PACT360 grants for a total of $1.2 million from the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant Program. An enforcement-led effort, PACT360 provides education to parents, youth, and community leaders about the risks and consequences of youth drug use. Many government-private partnerships have been formed through PACT360. To date, lead law enforcement agencies have been recruited in more than 30 states. (Action Item 1.4B)

In 2010, ONDCP awarded $800,000 to 12 HIDTAs to support participation in drug awareness and education activities. Currently, 20 of the 28 HIDTAs participate in prevention initiatives. Using evidence-based prevention practices, HIDTA members partner with community-based coalitions and organizations to better tailor prevention messages to youth, share time and personnel resources with local law enforcement agencies, and use juvenile justice programs to prevent and reduce gang and other criminal activity. (Action Item 1.4A)

Safe & Sound, Milwaukee, WI

In April 2010, the Milwaukee HIDTA received the Outstanding HIDTA Prevention Effort award for its Safe & Sound program. Safe & Sound is a partnership of law enforcement, prosecutors, youth-serving organizations, elected and civic leaders, businesses, city services, and clergy aimed at reducing drug use and crime and rebuilding neighborhoods. The project organizes residents and youth and connects them with these groups to identify and report criminal activity and prevent youth gang affiliation, crime, and substance abuse. Safe and Sound does so by utilizing interdependent strategies of positive youth development at after-school “Safe Places”, neighborhood organizing through its “Safe & Sound Community Partners” program, and tough law enforcement. It is a unique, collaborative approach to fighting crime, violence, illegal drug and alcohol sales, and other neighborhood problems. Safe & Sound’s collaborating partners empower youth and adults to work together, creating a better, safer community for all. After-school Safe Places for youth operate during the hours when youth are most apt to commit, or become victims of, crime. Engaging more than 20,000 young people every year, the Safe Places involve them in youth-led crime reduction and neighborhood improvement projects, drug and alcohol prevention activities, and gang resistance and violence prevention efforts. Programs offered include structured activities to help youth develop personal and social skills through interactive forms of learning. Safe & Sound Community Partners are community organizers, who conduct year-round door-to-door visits in high-crime neighborhoods to listen to and address the individual concerns of residents. These organizers recruit youth to attend Safe Places, and they work with youth leaders to implement community anti-crime initiatives. In conjunction with residents, Community Partners organize block watches, thereby building relationships and communication between residents, law enforcement and city services. Partners develop neighborhood-based initiatives, enhancing safety, reducing crime, positively affecting the community, and improving the overall quality of life for residents.

Principle 5. Preventing Drugged Driving Must Become a National Priority on Par with Preventing Drunk Driving

Each year thousands of drivers, passengers, and pedestrians tragically lose their lives because of impaired and distracted driving. This reckless behavior not only includes drunk driving, but also driving after taking drugs. The use of drugs, including prescription drugs, can impair judgment and motor skills.

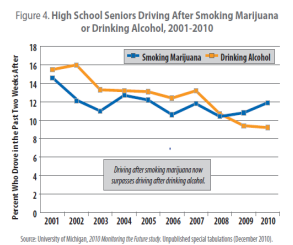

The data on the risks of drugged driving are compelling. Among drivers killed in motor vehicle crashes with known drug test results, one in three tested positive for drugs. In a 2007 roadside survey conducted by the Department of Transportation (DOT), one in eight nighttime weekend drivers tested positive for an illicit drug. This number rose to one in six when pharmaceuticals with the potential to impair driving (i.e., opioid pain relievers, tranquilizers, sedatives, and stimulants) were included. Additionally, according to the most recent Monitoring the Future (MTF) Study—the Nation’s largest survey of drug use among young people—one in eight high school seniors reported that in the 2 weeks prior to the survey, they had driven after smoking marijuana, a 14 percent increase over 2008.

The Administration has made combating drugged driving a drug control strategy priority and has set a goal of reducing the prevalence of drugged driving by 10 percent by 2015. To better understand the threat posed by drugged driving and to aid in developing an appropriate response, NIDA and ONDCP convened a multidisciplinary meeting in 2010 to establish a research agenda on the topic and started defining protocols to detect the presence of specific drugs, such as smoked marijuana and MDMA (Ecstasy). (Action Item 1.5E)

In addition to supporting NIDA in this important effort, ONDCP works with other Federal agencies to highlight the problem of drugged driving and reduce its prevalence. For example, ONDCP is working with national associations and experts to raise awareness of the dangers of drugged driving, provide technical assistance to states considering anti-drugged driving laws, and provide law enforcement with the tools it needs to effectively detect and prosecute drugged drivers. Already, 17 states have per se or zero tolerance statutes. (Action Item 1.5A) In these states, it is a criminal offense to drive after taking illegal drugs while the drugs are still detectable in one’s system. ONDCP has partnered with youth and community organizations such as the National Organization for Youth Safety, as well as state and local law enforcement, prosecutors, courts, and DMVs to help educate and enhance public awareness of the alarming prevalence of drivers on roadways with drugs in their systems. (Action Item 1.5C)

Domestic law enforcement agencies are also partnering to reduce the prevalence of drugged driving. NHTSA and ONDCP will provide funding to develop an online version of the Advanced Roadside Impaired Driving Enforcement (ARIDE) program. ARIDE will bridge key gaps in the training of law enforcement officers to better identify and assess drivers suspected of driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs. The online ARIDE program will provide this important training in a consolidated, online application that enables trainees to become more familiar with the key points of identifying a drugged driver, effectively providing training more quickly to more officers, and at lower costs. Trained officers can immediately use these new skills to identify and assist in removing drugged drivers from the road. (Action Item 1.5D)

The Facts About Marijuana

Marijuana

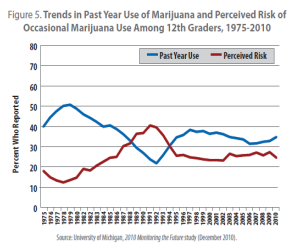

Marijuana use is the highest it has been in 8 years. In 2010, daily marijuana use increased significantly among all three grades surveyed (8th, 10th, and 12th graders) in the MTF study. Daily use for high school seniors increased from 5.2 percent to 6.1 percent of the respondents. One in 11 people who start marijuana use will become addicted—a rate that rises to one in six when use begins during adolescence. In 2009, marijuana was involved in 376,000 emergency department visits nationwide.

Making matters worse, confusing messages being conveyed by the entertainment industry, media, proponents of “medical” marijuana, and political campaigns to legalize all marijuana use perpetuate the false notion that marijuana use is harmless and aim to establish commercial access to the drug. This significantly diminishes efforts to keep our young people drug free and hampers the struggle of those recovering from addiction.

Marijuana and other illicit drugs are addictive and unsafe especially for use by young people. The science, though still evolving in terms of long-term consequences, is clear: marijuana use is harmful. Independent from the so called “gateway effect”—marijuana on its own is associated with addiction, respiratory and mental illness, poor motor performance, and cognitive impairment, among other negative effects.

Despite successful political campaigns to legalize “medical” marijuana in 15 states and the District of Columbia, the cannabis (marijuana) plant itself is not medicine. While there may be medical value in some of the individual components of the cannabis plant, the fact remains that smoking marijuana is an inefficient and harmful method for delivering the constituent elements that have or may have medicinal value. As always, the FDA process remains the only scientific and legally recognized procedure for bringing safe and effective medications to the American public. To date, the FDA has not found smoked marijuana to be either safe or effective medicine for any condition (see more on medical marijuana below).

The Administration steadfastly opposes drug legalization. Legalization runs counter to a public health approach to drug control because it would increase the availability of drugs, reduce their price, undermine prevention activities, hinder recovery support efforts, and pose a significant health and safety risk to all Americans, especially our youth.

Many “quick fixes” for America’s complex drug problem have been presented throughout our country’s history. In the past half-century, these proposals have included calls for allowing the legal sale and use of marijuana. However, the complex policy issues concerning drug use and the disease of addiction do not lend themselves to such simple solutions.

On November 2, 2010, Californians rejected one simplistic solution (Proposition 19) that would have legalized marijuana in their state. Parents, community and business leaders, and other concerned citizens realized marijuana legalization was a gamble they were not willing to take. Our Administration opposed Proposition 19 and was joined by a number of political figures, including candidates for governor and U.S. Senate. In the months leading up to the vote, the RAND Corporation released two independent studies that examined the theory that California would realize a net benefit from legalization and see reductions in the illicit proceeds and violence associated with drug trafficking.

The first RAND study appraised the claim that California would realize financial gains from marijuana legalization. Counter to proponents’ assertions, the study concluded that the pretax retail price of marijuana in California would decline by as much as 80 percent to levels not seen in 30 years due to less legal risk for suppliers, more automation, and economies of scale through farm field and greenhouse production. They concluded that the retail price would have been dependent upon the taxes (sales and excise), the structure of the regulatory scheme, and how taxes and regulations would be enforced. Moreover, the revenue from taxes would be dependent upon the compliance rate: by growing their own marijuana or purchasing it on the gray market, some consumers could avoid the taxes.

In addition, while proponents of Proposition 19 argue the high cost of enforcing existing marijuana laws (an amount they suggest is nearly $2 billion) renders legalization a compelling course of action, the RAND study estimates these costs to be dramatically lower ($300 million). Finally, the RAND report raises a powerful counter to the arguments made by proponents of Proposition 19, namely that legalizing marijuana would result in increased consumption of the drug.

Legalization supporters have also claimed that illicit profits to Mexican traffickers and violence in both Mexico and the United States would be reduced if drugs were sold on the open market. A second RAND study examined this argument and found that marijuana accounts for only about 15 to 26 percent of Mexican traffickers’ revenue (or about $1.5 to $2.0 billion) and therefore, legalization in California—which accounts for about one-seventh of U.S. marijuana consumption—would likely only reduce drug trafficking organizations’ profits by between 2 and 4 percent. The extent of such smuggling would depend upon the actions of Federal and state governments to prevent this illicit commerce.

Ultimately, RAND concluded that any projections with respect to reduced revenues leading to less violence are particularly uncertain. The researchers found that some mechanisms (i.e., disruptions in the illicit workforce due to declining revenues) suggest a large decline in revenues might provoke increased violence in the short-term but reduced violence after several years.

Controls and prohibitions help to keep prices higher, and higher prices help keep use rates relatively low. This is because drug use, especially among young people, is known to be sensitive to price.

Our current legal drugs—alcohol and tobacco—are examples of commercialized products with addiction potential and high usage rates fueled by easy availability. Although these products are taxed, neither produces a net economic benefit to society. The healthcare and criminal justice costs associated with alcohol and tobacco far surpass the tax revenue they generate, and little of the taxes collected on these substances is contributed to the offset of their substantial social and health costs.

Federal excise taxes collected on alcohol in 2007 totaled around $9 billion,51 and states collected around $5.6 billion. Taken together, this is less than 10 percent of the more than $185 billion in alcohol-related social costs such as healthcare, lost productivity, and criminal justice system expenses. Nor does tobacco carry its economic weight when taxed: each year, tobacco use generates only about $23 billion in taxes but results in more than $183 billion per year in direct medical expenses as well as lost productivity.

Further, our current experience with legal, regulated prescription drugs shows that legalizing drugs only widens their availability and potential for abuse, no matter what controls are in place. In 2007, drug-induced deaths climbed to more than 38,000, according to CDC. This increase was driven primarily by drug overdose deaths from the non-medical use of legal pharmaceutical drugs, particularly narcotic pain relievers.

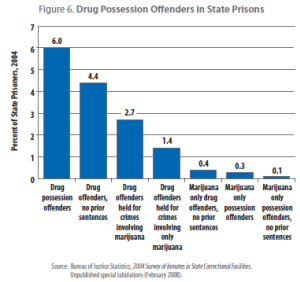

Advocates of legalization say the costs of prohibition, mainly through the criminal justice system, place a great burden on taxpayers and governments. While there are certainly costs to current prohibitions, legalizing drugs would not cut costs associated with the criminal justice system (see figure). Arrests for alcohol-related crimes, such as violations of liquor laws and driving under the influence, totaled nearly 2.7 million in 200857—far more than arrests for all illegal drug use. These alcohol-related arrests are costly. Legalizing marijuana would further saddle government with the dual burden of regulating a new legal market while continuing to pay for the negative effects associated with an underground market whose providers have little economic incentive to disappear.

At a time when our efforts should be focused on reversing a troubling increase in drug use, legalization would only make matters worse by lowering the drug’s price, increasing its use, and creating billions of dollars in new social costs.

‘Medical’ Marijuana

Marijuana and other drugs are addictive and unsafe, especially for use by young people. Unfortunately, efforts to “medicalize” marijuana have widened the public acceptance and availability of the drug.

There is no substitute for the scientific approval process employed by the FDA. For a drug to be made available to the public as medicine, the FDA requires rigorous research followed by tests for safety and efficacy. Only then can a substance be classified as medicine and prescribed by qualified health care professionals to patients.

In the wake of state and local laws that permit distribution of “medical” marijuana, dozens of localities have been left to grapple with poorly written laws that bypass the FDA process and allow marijuana to be used as a so-called medicine. John Knight, director of the Center for Adolescent Substance Abuse Research at Children’s Hospital Boston, recently wrote: “Marijuana has gotten a free ride of sorts among the general public, who view it as non-addictive and less impairing than other drugs. However, medical science tells a different story.”

Similarly, Christian Thurstone, a board-certified Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, an Addiction Psychiatrist, and also an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Colorado, said:

“In the absence of credible data, this debate is being dominated by bad science and misinformation from people interested in using medical marijuana as a step to legalization for recreational use. Bypassing the FDA’s well-established approval process has created a mess that especially affects children and adolescents. Young people, who are clearly being targeted with medical marijuana advertising and diversion, are most vulnerable to developing marijuana addiction and suffering from its lasting effects.” —Dr. Christian Thurstone, MD, Assistant Professor at Denver Health & Hospital Authority

In the United States, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has approved 109 researchers to perform bona fide research with marijuana, marijuana extracts, and marijuana derivatives such as cannabidiol and cannabinol. Studies include evaluation of abuse potential, physical/psychological effects, adverse effects, therapeutic potential, and detection. Fourteen researchers are approved to conduct research with smoked marijuana on human subjects.

As a result of this extensive research, several marijuana-based medications have been found to be safe and effective by the FDA and are available for doctors to prescribe. Dronabinol, a synthetic form of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the most active ingredient in marijuana, is used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy. It is also used to treat loss of appetite and weight loss in people who have AIDS. Nabilone, a synthetic drug that mimics marijuana’s main ingredient, is also prescribed to treat nausea and vomiting caused by cancer chemotherapy. Other medications based on one or more marijuana components are being carefully studied.

Aside from the problems accompanying the commercialization of marijuana, smoking any drug is unhealthy. That is why no major medical association has come out in favor of smoked marijuana for widespread medical use. For example, the American Cancer Society, American Glaucoma Foundation, National Pain Foundation, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and other medical societies are not in favor of smoked “medical” marijuana. The American Medical Association has called for more research on the subject, with the caveat that this “should not be viewed as an endorsement of state-based medical cannabis programs, the legalization of marijuana, or that scientific evidence on the therapeutic use of cannabis meets the current standards for a prescription drug product.”

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics:

Evidence suggests that pediatricians should continue their vigilant efforts to prevent the use of this drug by young people. The abuse of marijuana by adolescents is a major health problem with social, academic, developmental, and legal ramifications. Marijuana is an addictive, mind-altering drug capable of inducing dependency. Pediatricians are obligated to develop a reasoned approach to dealing with its use by children and adolescents so they can provide appropriate care and counsel… Additional reasons for concern and counsel include anxieties and uncertainties about the potential harm that marijuana use may cause to adolescents during a period of rapid change in hormonal secretion, possible teratogenicity, and the known consequences of long-term use.

This Administration joins major medical societies in supporting increased research into marijuana’s many components, delivered in a safe (non-smoked) manner, in the hopes that they can be available for physicians to legally prescribe when proven to be safe and effective. Outside the context of Federally approved research, the use and distribution of marijuana is prohibited in the United States.