Circular A-129

Circular No. A-129

Policies for Federal Credit Programs

and Non-Tax Receivables

Executive Office of the President

Office of Management and Budget

January 2013

Table of Contents

I. RESPONSIBILITIES OF DEPARTMENTS AND AGENCIES

A. Office of Management and Budget.

B. Department of the Treasury.

C. Federal Credit Policy Council.

II. BUDGET AND LEGISLATIVE POLICY FOR CREDIT PROGRAMS

A. Program Reviews and Evidence-Building.

III. CREDIT EXTENSION AND MANAGEMENT POLICY

C. Management of Guaranteed Loan Lenders and Servicers.

IV. MANAGING THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT’S RECEIVABLES

A. Accounting and Financial Reporting.

B. Loan Servicing Requirements.

A. Standards for Defining Delinquent and Defaulted Debt.

B. Administrative Collection of Debts.

C. Referrals to the Department of Justice.

D. Interest, Penalties and Administrative Costs.

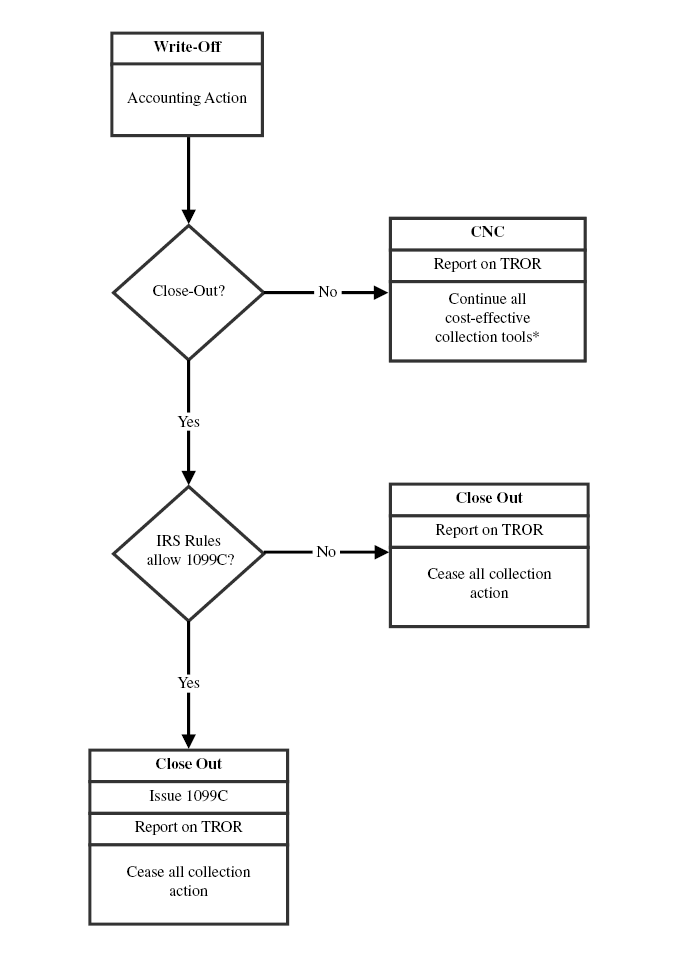

E. Termination of Collection, Write-Off, Use of Currently

Not Collectible (CNC), and Close-Out.

ATTACHMENT: Write-Off/Close-out Processes for Receivables

Appendix B: Model Bill Language for Credit Programs

Appendix C: Management and Oversight Structures

Appendix D: Effective Reporting for Data-Driven Decision Making

Appendix E: Communications Policies

I. RESPONSIBILITIES OF DEPARTMENTS AND AGENCIES

|

References |

|

|

Statutory |

Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA), 2 U.S.C. § 661 et. seq. Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA), 31 U.S.C. §3701, 3711-3720E Federal Debt Collection Procedures Act of 1990 Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 Budget and Accounting Act of 1950 |

A. Office of Management and Budget. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is responsible for reviewing legislation to establish new credit programs or to expand or modify existing credit programs; monitoring agency conformance with the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA); formulating and reviewing agency credit reporting standards and requirements; reviewing and clearing testimony pertaining to credit programs and debt collection; reviewing agency budget submissions for credit programs and debt collection activities; developing and maintaining the Federal credit subsidy calculator used to calculate the cost of credit programs; formulating and reviewing agency implementation of credit management and debt collection policy; approving agency credit management and debt collection plans; working with agencies to identify and implement common policies, processes, or other resources to increase efficiency of credit program portfolio management functions; and providing training to credit agencies.

B. Department of the Treasury. The Department of the Treasury (Treasury), acting through the Office of Domestic Finance, works with OMB to develop Federal credit policies and review legislation to create new credit programs or to expand or modify existing credit programs. Treasury, through its Financial Management Service (FMS), promulgates Government-wide debt collection regulations implementing the debt collection provisions of the Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA). FMS works with the Federal program agencies to identify debt that is eligible for referral to Treasury for cross-servicing and offset, and to establish target dates for referral. Performance measures for annual referral and collection goals are set in conjunction with FMS, agencies, and OMB. In accordance with the DCIA and other Federal laws, FMS conducts offsets of eligible Federal and State payments, including tax refunds, to collect Federal non-tax debts, as well as State debts, through the Treasury Offset Program (TOP). FMS also provides collection services for delinquent non-tax Federal debts (referred to as cross-servicing), and maintains a private collection agency contract for referral and collection of delinquent debts. Additionally, FMS issues operational and procedural guidelines regarding Government-wide credit management and debt collection such as Managing Federal Receivables and Guide to the Federal Credit Bureau Program. FMS, under its program responsibility for credit and debt management and as an active member of the Federal Credit Policy Council, assists in improving credit and debt management activities Government-wide.

C. Federal Credit Policy Council. The Federal Credit Policy Council (FCPC) is an interagency forum convened by OMB that a) provides advice and assistance to OMB and Treasury in the formulation and implementation of credit policies, and b) serves as a mechanism to foster interagency collaboration and sharing of best practices. Membership consists of representatives from OMB and other representatives from the Executive Office of the President, Treasury, and the Chief Financial Officer (CFO), Chief Risk Officer and other senior official(s) from each participating Federal credit or debt collection agency. The major credit and debt collection agencies represented include the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Justice, Labor, State, Transportation, Veterans Affairs and the Agency for International Development, the Export-Import Bank, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and the Small Business Administration. Other departments and agencies may be invited to participate in the FCPC. The FCPC will establish standing and ad-hoc work groups as needed to focus on issues specific to Federal credit programs and debt collection.

D. Department and Agencies. Departments and agencies shall manage credit programs and all non-tax receivables in accordance with their statutory authorities and the provisions of this Circular to protect the Government’s assets and to minimize losses in relation to social benefits provided. Specifically, agencies shall ensure that Federal credit program legislation, regulations, and policies are designed and administered in compliance with the principles of this Circular; the costs of credit programs are budgeted for and controlled in accordance with FCRA; and that credit programs are designed and administered in a manner that most effectively and efficiently achieves policy goals while minimizing taxpayer risk.

To achieve these objectives, agencies shall:

1. Ensure that the statutory and regulatory requirements and standards set forth in this and other applicable OMB circulars, Treasury regulations, and supplementary guidance set forth in the Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables are incorporated into agency regulations, policies, and procedures for credit programs and debt collection activities;

2. Propose new or revised legislation, regulations, and forms as necessary to ensure consistency with the provisions of this Circular;

3. Submit legislation and testimony affecting credit programs for review under OMB Circular No. A-19, Legislative Coordination and Clearance and budget proposals for review under OMB Circular No. A-11, Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget;

4. Operate each credit program under a robust management and oversight structure, with clear and accountable lines of authority and responsibilities for administering programs and independent risk management functions; monitoring programs in terms of programmatic goals and performance within acceptable risk thresholds; and taking action to improve or maintain efficiency and effectiveness;

5. Make every effort to effectively target Federal assistance, and mitigate risk by a) following appropriate screening standards and procedures for eligibility and determination of creditworthiness, and b) making sure that lenders and servicers participating in Federal credit programs meet all applicable financial and programmatic requirements;

6. Establish appropriate internal controls over programmatic functions and operations, in accordance with the standards established in this Circular, and OMB Circular No. A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Internal Control;

7. Assign to the agency CFO, in accordance with the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act), responsibility for directing, managing, and providing policy guidance and oversight of agency financial management personnel, activities, and operations, including the implementation of asset management systems for credit management and debt collection;

8. Establish oversight and governance structures, as appropriate, to coordinate credit management and debt collection activities, and ensure full consideration of credit management and debt collection issues by all interested and affected Federal organizations;

9. Employ robust diagnostic and reporting frameworks, including dashboards and watch lists, so that all levels of the organization receive appropriate information to inform proactive portfolio management, and program decisions are informed by robust data analytics that provide senior policy officials and other credit program managers a clear understanding of a program’s performance towards policy goals and risk, and the effects of such decisions;

10. Evaluate Federal credit programs’ effectiveness in achieving program goals in accordance with the guidance set forth in this Circular and in OMB Circular No. A-11, Part 6, including strategic program reviews at least once every two years, or under other such timeframe as approved by OMB;

11. Ensure that informed and cost effective decisions are made concerning portfolio administration, including full consideration of contracting out for servicing or selling the portfolio;

12. Effectively manage delinquent debt, including the use of all available techniques, as appropriate, to collect delinquent debts, such as those found in the Federal Claims Collection Standards and Treasury regulations, including demand letters, administrative offset, salary offset, tax refund offset, private collection agencies, cross-servicing by Treasury, administrative wage garnishment, and litigation, and the write-off of delinquent debts as soon as they are determined to be uncollectible;

13. Submit timely and accurate financial management and performance data to OMB and Treasury, to support evaluation of the Government’s credit management and debt collection programs and policies;

14. Prepare, as part of the agency CFO Financial Management 5-Year Plan, a Credit Management and Debt Collection Plan for effectively managing credit extension, account servicing, portfolio management and delinquent debt collection. The plan must ensure agency compliance with the standards in this Circular; and

15. Manage data in loan applications and documents for individuals in accordance with the Privacy Act of 1974, as amended by the Computer Matching and Privacy Protection Act of 1988, and the Right to Financial Privacy Act of 1978, as amended. The Privacy Act of 1974 does not apply to loans and debts of commercial organizations.

II. BUDGET AND LEGISLATIVE POLICY FOR CREDIT PROGRAMS

Federal credit assistance should be provided only when it is necessary and the best method to achieve clearly-specified Federal objectives. Use of private credit markets should be encouraged, and any impairment of such markets or misallocation of the nation’s resources through the operation of Federal credit programs should be minimized.

A. Program Reviews and Evidence-Building.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA), 2 U.S.C. § 661 et. seq. |

|

Guidance |

|

Agencies shall periodically evaluate programs in terms of the policy goals of the program, and the program’s effectiveness towards addressing those goals. Such reviews should be performed on a biennial basis, or other timeframe approved by OMB. Program reviews should be written analyses submitted to OMB as part of the agency’s budget request, or other mechanism acceptable to OMB, along with electronic copies of completed evaluations and other studies. (For guidance on program evaluation and evidence required in support of the agency’s budget submission, see OMB Memorandum M-12-14.) Agencies may be required to perform such reviews or evidence-building more frequently for significant programs or programs experiencing a major change, such as a change in purpose or scope, a change in how the program is administered, or a change in external factors that are likely to affect program operations, impact, and/or cost. In addition, program reviews should be submitted to OMB for new credit programs, and for reauthorizing, expanding, or significantly changing existing credit programs. Such reviews should explain the rationale for proposed changes, provide evidence (evaluations and other strong analytics about relevant data) of past program impacts, and, if new delivery designs are being proposed, lay out why the design changes are expected to improve program impact or costs. Credit program reviews under this section must address, at a minimum:

1. The Federal objectives to be achieved, including:

a. Whether the credit program is intended to:

i. Correct a capital market imperfection, which should be defined and quantified;

ii. Subsidize borrowers or other beneficiaries, who should be identified; and/or

iii. Encourage certain activities, which should be specified.

b. Why they cannot be achieved without Federal credit assistance, including:

i. A description of existing and potential private sources of credit by type of institution, and the availability, terms and conditions, and cost of credit to borrowers;

ii. An explanation as to whether and why these private sources of financing must be supplemented and/or subsidized; and

iii. Whether any Federal credit or non-credit program exists that addresses a similar need and why it or a modification to it would not be sufficient to address the need.

2. The scope of the program, including the amount of Federal credit assistance estimated necessary to efficiently meet the intended Federal objectives, and where appropriate, the time horizon of Federal investment.

3. The justification for use of a credit subsidy. The review should provide an explanation of why a credit subsidy is the most efficient way of providing assistance, including how it aids in overcoming capital market imperfections, how it would assist the identified borrowers or beneficiaries or would encourage the identified activities, why it would be preferable to other forms of assistance such as grants or technical assistance, and the degree of subsidy necessary to achieve the Federal objectives.

4. The estimated net economic benefits of the program or program change. The review should estimate or, when the program exists, measure the benefits expected from the program or program change, including the amount by which the distribution of credit is expected to be altered and the favored activity is expected to increase, and analyze any economic costs associated with the program. Information on conducting a cost-benefit analysis can be found in OMB Circular No. A-94.

5. The effects on private capital markets. The review should estimate the extent to which the program substitutes directly or indirectly for private lending, and analyze any elements of program design that encourage and supplement private lending activity, with the objective that private lending is displaced to the smallest degree possible by agency programs.

6. The estimated subsidy level. The review should provide an explicit estimate of the subsidy, as required by FCRA. If loan assets are to be sold or are to be included in a prepayment program for programmatic or other reasons, then the subsidy estimate should include the effects of the loan asset sales. For guidance on loan asset sales, see the DCIA, OMB Circular No. A-11, and the Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables. Loan asset sales/prepayment programs must be conducted in accordance with policies in this Circular and procedures in Managing Federal Receivables, including the prohibitions against the financing of prepayments by tax-exempt borrowing and sales with recourse except where specifically authorized by statute. The cost of any guarantee placed on the asset sold requires budget authority.

7. The administrative resource requirements. The review should include an examination of the agency’s current capacity to administer the new or expanded program and an estimation of any additional resources that would be needed, and an explicit estimate of the expected annual administrative costs including extension, servicing, collection, and management and oversight functions.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA), 2 U.S.C. § 661 et. seq. |

When Federal credit assistance is necessary to meet a Federal objective, loan guarantees should be favored over direct loans, unless attaining the Federal objective requires a subsidy, deeper than can be provided by a loan guarantee.

1. Loan guarantees may provide several advantages over direct loans. These advantages include: private sector credit servicing (which tends to be more efficient), private sector analysis of the borrower’s creditworthiness (which tends to allocate resources more efficiently), involvement of borrowers with private sector lenders (which promotes their movement to private credit), and lower portfolio management costs for agencies.

2. Loan guarantees, by removing part or all of the credit risk of a transaction, change the allocation of economic resources. Loan guarantees may make credit available when private financial sources would not otherwise do so, or guarantees may support credit to borrowers under more favorable terms than would otherwise be granted. This reallocation of credit may impose a cost on the Government and/or the economy.

3. Direct loans usually offer borrowers lower interest rates and longer maturities than loans available from private financial sources, even those with a Federal guarantee. The use of direct loans, however, may displace private financial sources and increase the possibility that the terms and conditions on which Federal credit assistance is offered will not reflect changes in financial market conditions. The costs to the Government and the economy are therefore likely to be greater.

4. Direct or indirect guarantees of tax-exempt obligations are prohibited under Section 149(b) of the Internal Revenue Code. Guarantees of tax-exempt obligations are an inefficient way of allocating Federal credit. Assistance to the borrower, through the tax exemption and the guarantee, provides interest savings to the borrower that are smaller than the tax revenue loss to the Government. It is generally thought that the cost to the taxpayer is greater than the benefit to the borrower. The Internal Revenue Code provides some exceptions to this requirement; see Section 149(b) for further details.

5. To preclude the possibility that Federal agencies will guarantee tax-exempt obligations, either directly or indirectly, agencies will:

a. Not guarantee federally tax-exempt obligations;

b. Provide that effective subordination of a direct or guaranteed loan to tax-exempt obligations will render the guarantee void. To avoid effective subordination, the direct or guaranteed loan and the tax-exempt obligation should be repaid using separate dedicated revenue streams or otherwise separate sources of funding, and should be separately collateralized. In addition, the direct or guaranteed loan terms, such as grace periods, repayment schedules, and availability of deferrals, should be consistent with private sector standards to ensure that they do not create effective subordination;

c. Prohibit use of a Federal guarantee as collateral to secure a tax-exempt obligation;

d. Prohibit Federal guarantees of loans funded by tax-exempt obligations; and

e. Prohibit the linkage of Federal guarantees with tax-exempt obligations. For example, such prohibited linkage occurs if the project is unlikely to be financed without the Federal guarantee covering a portion of the cost. In such cases, the Federal guarantee is, in effect, enabling the tax-exempt obligation to be issued, since without the guarantee the project would not be viable to receive any financing. Therefore, the tax-exempt obligation is dependent on and linked to the Federal guarantee.

6. Where a large degree of subsidy is justified, comparable to that which would be provided by guaranteed tax-exempt obligations, agencies should consider the use of direct loans.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA), 2 U.S.C. § 661 et. seq. |

|

Guidance |

Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board: Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards No. 2 Accounting for Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees, as amended; Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards No. 18 Amendments to Accounting Standards for Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees; and Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards No. 19 Technical Amendments to Accounting Standards for Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees in Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards No. 2. |

In accordance with FCRA, agencies must analyze and control the risk and cost of their programs.

Agencies must develop statistical models predictive of defaults and other deviations from loan contracts. Agencies are required to estimate subsidy costs and to obtain budget authority to cover such costs before obligating direct loans and committing loan guarantees. Specific instructions for budget justification, subsidy cost estimation (including analytical support for model assumptions), and budget execution under FCRA are provided in OMB Circular No. A-11.

Agencies shall follow sound financial practices in the design and administration of their credit programs. Where program objectives cannot be achieved while following sound financial practices, the cost of these deviations shall be justified in agency budget submissions with a cost-benefit analysis and all deviations should be reevaluated in any program review performed under the requirements above. Unless a deviation has been approved by OMB, agencies should follow the financial practices discussed below.

1. Lenders and borrowers who participate in Federal credit programs should have a substantial stake in full repayment in accordance with the loan contract.

a. Private lenders who extend credit that is guaranteed by the Government should bear at least 20 percent of the loss from a default. Loan guarantees that cover 100 percent of any losses on a loan encourage private lenders to exercise less caution than they otherwise would in evaluating loan requests. The level of guarantee should be no more than necessary to achieve program purposes. Loans for borrowers who are deemed to pose less of a risk should receive a lower guarantee.

b. Borrowers should have an equity interest in any asset being financed with the credit assistance, and business borrowers should have substantial capital or equity at risk in their business (see Section III.A.3.b for additional discussion).

c. Programs in which the Government bears more than 80 percent of any loss should be periodically reviewed to determine whether the private sector has become able to bear a greater share of the risk.

2. Agencies should establish interest and fee structures for direct loans and loan guarantees and should review these structures at least annually. Documentation of the performance of these annual reviews for credit programs is considered sufficient to meet the review requirement described in Section 902(a)(8) of the CFO Act.

a. Interest and fees should be set at levels that minimize default and other subsidy costs, of the direct loan or loan guarantee, while supporting achievement of the program’s policy objectives.

b. Agencies must request an appropriation in accordance with FCRA for default and other subsidy costs not covered by interest and fees.

c. Unless inconsistent with program purposes, and where authorized by law, riskier borrowers should be charged more than those who pose less risk. In order to avoid an unintended additional subsidy to riskier borrowers within the eligible class and to support the extension of credit to those riskier borrowers, programs that, for public policy purposes, do not adhere to this guideline, should justify the extra subsidy conveyed to the higher-risk borrowers in their annual budget submissions to OMB.

3. Contractual agreements should include all covenants and restrictions (e.g., liability insurance) necessary to protect the Federal Government’s interest.

a. Maturities on loans should be shorter than the estimated useful economic life of any assets financed.

b. The Government’s claims should not be subordinated to the claims of other creditors, as in the case of a borrower’s default on either a direct loan or a guaranteed loan. Subordination increases the risk of loss to the Government, since other creditors would have first claim on the borrower’s assets.

4. In order to minimize inadvertent changes in the amount of subsidy, interest rates to be charged on direct loans and any interest supplements for guaranteed loans should be specified by reference to the market rate on a benchmark Treasury security rather than as an absolute level. A specific fixed interest rate should not be cited in legislation or in regulation, because such a rate could soon become outdated, unintentionally changing the extent of the subsidy.

a. The benchmark financial market instrument should be a marketable Treasury security with a similar maturity to the direct loans being made or the non-Federal loans being guaranteed. When the rate on the Government loan is intended to be different than the benchmark rate, it should be stated as a percentage of that rate. The benchmark Treasury security must be cited specifically in agency budget justifications.

b. Interest rates applicable to new loans should be reviewed at least quarterly and adjusted to reflect changes in the benchmark interest rate. Loan contracts may provide for either fixed or floating interest rates.

5. Maximum amounts of direct loan obligations and loan guarantee commitments should be specifically authorized in advance in annual appropriations acts, except for mandatory programs exempt from the appropriations requirements under Section 504(c) of FCRA.

6. Financing for Federal credit programs should be provided by Treasury in accordance with FCRA. Guarantees of the timely payment of 100 percent of the loan principal and interest against all risk create a debt obligation that is the credit risk equivalent of a Treasury security. Accordingly, a Federal agency other than the Department of the Treasury may not issue, sell, or guarantee an obligation of a type that is ordinarily financed in investment securities markets, as determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, unless the terms of the obligation provide that it may not be held by a person or entity other than the Federal Financing Bank (FFB) or another Federal agency. In exceptional circumstances, the Secretary of the Treasury may waive this requirement with respect to obligations that the Secretary determines: 1) are not suitable for investment for the FFB because of the risks entailed in such obligations; or 2) are, or will be, financed in a manner that is least disruptive of private finance markets and institutions; or 3) are, or will be, based on the Secretary’s consultation with OMB and the guaranteeing agency, financed in a manner that will best meet the goals of the program. The benefits of using the FFB must not expand the degree of subsidy.

7. Federal loan contracts should be standardized where practicable. Documents similar to those used in the private sector should be used whenever possible, especially for loan guarantees.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA), 2 U.S.C. § 661 et. seq. |

|

Guidance |

|

The provisions of Section II will be implemented through the OMB Circular No. A-19 legislative review process and the OMB Circular No. A-11 budget justification and submission process. For accounting standards for Federal credit programs, see the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board standards: Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards No. 2 (SSFAS) Accounting for Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees, as amended by SFFAS No. 18 and No. 19.

1. Proposed legislation on credit programs, reviews of credit proposals made by others, and testimony on credit activities submitted by agencies under the OMB Circular No. A-19 legislative review process should conform to the provisions of this Circular.

Whenever agencies propose provisions or language not in conformity with the policies of this Circular, they will be required to provide justification in writing to OMB for a deviation from the requirement, and state the time period for which the deviation is requested. Deviations, where granted, will typically be time-limited, and must be periodically reevaluated as part of the program review (Section II.A).

2. Additional guidance for program reviews of legislative and budgetary proposals is included as Appendix A to this Circular. Agencies should use the model bill language provided in Appendix B in developing and reviewing authorizing legislation, unless OMB has approved the use of alternative language that includes the same substantive elements.

3. Every two years, or on an alternate schedule approved by OMB, the agency’s annual budget submission (required by OMB Circular No. A-11, Section 25) should include the program review in Section II.A, and additional information including but not limited to:

a. The agency’s plan for periodic, results-oriented evaluations of the effectiveness of the program and program practices, and the use of relevant program evaluations and/or other analyses of program effectiveness or causes of escalating program costs. A program evaluation is a formal assessment, through objective measurement and systematic analysis, addressing the manner and extent to which credit programs achieve intended objectives. While agencies should generally conduct these evaluations at the program level, some analyses may be more appropriate at the level of the goals in agencies’ strategic plans and annual performance plans required by the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010. (For further guidance, please see OMB Circular No. A-11, Part 6);

b. A review of the changes in financial markets and the status of borrowers and beneficiaries to verify that the continuation of the credit program is required to meet Federal objectives, to update its justification, and to recommend changes in its design and operation to improve efficiency and effectiveness; and

c. Proposed changes to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of a program, including changes to correct those cases where existing legislation, regulations, or program policies are not in conformity with the policies of this Circular. When an agency does not deem a change in existing legislation, regulations, or program policies to be desirable, it will provide a justification for retaining the non-conformance.

III. CREDIT EXTENSION AND MANAGEMENT POLICY

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA), 31 U.S.C. §3701, 3711-3720E |

|

Regulatory |

Executive Order 13,019, Federal Register Vol. 61, No. 193, 51763 |

|

Guidance |

Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables, Treasury Report on Receivables (TROR), and Guide to the Federal Credit Bureau Program |

1. Applicant Screening.

a. Program Eligibility. Federal credit granting agencies and private lenders in guaranteed loan programs shall determine whether applicants comply with statutory, regulatory, and administrative eligibility requirements for loan assistance. Where consistent with program objectives, borrowers should be required to certify and document that they have been unable to obtain credit from private sources on reasonable terms. In addition, application forms must require the borrower to certify the accuracy of information being provided. (False information is subject to penalties under 18 U.S.C. § 1001.)

b. Delinquency on Federal Debt. Agencies should determine if the applicant is delinquent on any Federal debt, including tax debt. Agencies should include a question on loan application forms asking applicants if they have such delinquencies. In addition, agencies and guaranteed loan lenders shall use credit bureaus as a screening tool. Agencies are also encouraged to use other appropriate databases, such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Credit Alert Verification Reporting System and Treasury’s Do Not Pay List to identify delinquencies on Federal debt.

Processing of applications shall be suspended when applicants are delinquent on Federal tax or non-tax debts, including judgment liens against property for a debt to the Federal Government, and are therefore not eligible to receive Federal loans, loan guarantees or insurance. (See 31 U.S.C. § 3720B regarding non-tax debts.) This provision does not apply to disaster loans or a marketing assistance loan or loan deficiency payment under Subtitle C of the Agricultural Market Transition Act (7 U.S.C. 7231, et. seq.). Agencies should review and comply with 31 U.S.C. § 3720B and 31 C.F.R. 285.13 before extending credit. Processing should continue only when the debtor satisfactorily resolves the debts (e.g., pays in full or negotiates a new repayment plan).

c. Creditworthiness. Where creditworthiness is a criterion for loan approval, agencies and private lenders shall determine if applicants have the ability to repay the loan, taking into consideration the applicant’s history of repaying debt. Credit reports and supplementary data sources, such as financial statements and tax returns, should be used to verify or determine employment, income, assets held, and credit history.

d. Delinquent Child Support. Agencies shall deny Federal financial assistance to individuals who are subject to administrative offset to collect delinquent child support payments. See Executive Order 13,019, 61 Federal Register 51,763 (1996). The Attorney General has issued Minimum Due Process Guidelines: Denial of Federal Financial Assistance Pursuant to Executive Order 13,019, which agencies shall include in their procedures or regulations promulgated for the purpose of denying Federal financial assistance in accordance with Executive Order 13,019.

e. Taxpayer Identification Number. Pursuant to 31 U.S.C. § 7701(d), agencies must obtain the taxpayer identification number (TIN) of all persons doing business with the agency. All agencies and lenders extending credit shall require the applicant or borrower to supply a TIN as a prerequisite to obtaining credit or assistance.

2. Loan Documentation. Loan origination files should contain loan applications, credit bureau reports, credit analyses, loan contracts, and other documents necessary to conform to private sector standards for that type of loan. Accurate and complete documentation is critical to providing proper servicing of the debt, pursuing collection of delinquent debt, and in the case of guaranteed loans, processing claim payments. Additional information on documentation requirements is available in Managing Federal Receivables.

3. Collateral Requirements. For many types of loans, the Government can reduce its risk of default and potential losses through well managed collateral requirements.

a. Appraisals of Real Property. Appraisals of real property serving as collateral for a direct or guaranteed loan must be conducted in accordance with the following guidelines:

i. Agencies should require that all appraisals be consistent with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, promulgated by the Appraisal Standards Board of the Appraisal Foundation. Agencies shall prescribe additional appraisal standards as appropriate.

ii. Agencies should ensure that a State-licensed or certified appraiser prepares an appraisal for all credit transactions over $100,000 ($250,000 for business loans). (This does not include loans with no cash out and those transactions where the collateral is not a major factor in the decision to extend credit.) Agencies shall determine which of these transactions because of the size and/or complexity must be performed by a State-licensed or certified appraiser. Agencies may also designate direct or guaranteed loan transactions not exceeding $100,000 ($250,000 for business loans) that require the services of a State-licensed or certified appraiser.

b. Loan to Value Ratios. In some credit programs, the primary purpose of the loan is to finance the acquisition of an asset, such as a single family home, which then serves as collateral for the loan. Agencies should ensure that borrowers assume an equity interest in such assets in order to reduce defaults and Government losses. Federal agencies should explicitly define the components of the loan to value ratio (LTV) for both direct and guaranteed loan programs. Financing should be limited by not offering terms (including the financing of closing costs) that result in an LTV equal to or greater than 100 percent. Further, the loan maturity should be shorter than the estimated useful economic life of the collateral.

c. Liquidation of Real Property Collateral for Guaranteed Loans. In general, it is not in the Federal Government’s financial interest to assume the responsibility for managing and disposing of real property serving as collateral on defaulted guaranteed loans. Private lenders should be required to liquidate, through litigation if necessary, any real property collateral for a defaulted guaranteed loan before filing a default claim with the credit granting agency.

d. Asset Management Standards and Systems. Agencies should establish policies and procedures for the acquisition, management, and disposal of real property acquired as a result of direct or guaranteed loan defaults in a manner that is consistent with policy goals, maximizing efficiency and minimizing taxpayer cost. Agencies should establish inventory management systems to track all costs, including contractual costs, of maintaining and selling property. Inventory management systems should also generate management reports, provide controls and monitoring capabilities, and summarize information for OMB and Treasury. (See Treasury Report on Receivables (TROR).)

1. Management and Oversight. Agencies must have robust management and oversight frameworks for credit programs to monitor the program’s progress towards achieving policy goals within acceptable risk thresholds, and to take action where appropriate to increase efficiency and effectiveness. This framework must be reinforced with appropriate internal controls.

a. Lines of Authority, Program Goals, and Risk Thresholds. Agencies must have and should codify clearly-defined lines of authority and communication. Through these structures, management should establish explicit programmatic policy goals and acceptable risk thresholds, and metrics to evaluate the program’s effectiveness against these goals, and assess the program on an on-going basis.

i. Clearly-Defined Lines of Authority and Communication. Agency management frameworks may include councils or boards, and must include individuals with necessary program and/or financial expertise and stature. Representation should include, but not be limited to, the agency CFO, the Chief Risk Officer, and the senior official(s) for program offices with credit activities or non-tax receivables. Agency credit management may seek input from the agency’s Inspector General based on findings and conclusions from past audits and investigations.

ii. Performance and Other Indicators and Risk Thresholds. Senior management must also establish appropriate performance and other indicators for the program, and establish risk thresholds to balance policy goals with risks and costs to the taxpayer. Such indicators should be reviewed periodically, and coordinated with OMB. Agency management structures should clearly delineate accountable parties and responsibilities for:

a. Defining policy performance indicators linked to the statutory purpose of the program or to the underlying market failure that the credit program is designed to correct and the nature of the risks the program faces;

b. Reviewing and approving major risk-related policies, practices, underwriting standards, and policy performance metrics, and such policies as may delineate thresholds whereby additional approvals of potential credit assistance may be required;

c. Monitoring the efficiency and effectiveness of each program with respect to policy, risk management, and cost objectives; and

d. Assessing past performance and taking actions necessary to meet such goals more effectively and efficiently.

iii. Risk Management. Agencies should develop oversight and control functions that are sufficiently independent of program management and have expertise and stature within the organization to identify emerging issues using real-time information about the outstanding portfolio, including credit and operational risks.

b. Internal Controls for Credit Programs.

i. Separation of Duties. Federal credit agencies shall structure their programmatic operations in a manner that separates critical functions as appropriate, given the program structure and type of assistance. These critical functions may include:

a. Promoting the program to prospective applicants;

b. Reviewing and approving applications for credit assistance;

c. Monitoring and servicing the outstanding portfolio;

d. Reviewing and approving modifications to outstanding loans;

e. Collecting delinquent debts; and

f. Conducting comprehensive risk management.

ii. Communications Policy. Agencies shall establish and document a policy for communications with credit counterparties and other stakeholders, including but not limited to applicants and lenders, to govern interaction during any period when an agency decision on credit support is pending, or when there is a reasonable possibility that the terms and conditions of existing credit support may be amended.

The objective of the communications policy is to provide clear guidance regarding communications with non-Executive Branch entities, and should address the following points:

a. Identify the types of communications that are required, permissible, and prohibited, along with any accompanying rules and procedures;

b. Cover the agency’s employees and contractors and make clear who within the agency is responsible for handling such communications; and

c. Protect information that is business confidential, market sensitive, and/or pre-decisional and deliberative

iii. Outsourcing Programmatic Functions to Contractors. Agencies are responsible for determining whether to retain operations within the agency or to outsource some functions to outside parties. In making this determination, the agency should ensure that the best interests of taxpayers are protected.

a. Agencies must retain those responsibilities that are inherently Governmental and critical functions and take actions, before and after contract award, to prevent contractor performance of such functions and overreliance on contractors in “closely associated” and critical functions, as determined in accordance with Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) Policy Letter 11-01, Performance of Inherently Governmental and Critical Functions. Agencies are also required to develop agency-level procedures, provide training, and designate senior officials to be responsible for implementation of these policies.

b. In those cases where operations are outsourced, the agency should establish agreements to ensure appropriate oversight over contractor operations and procedures. Agencies shall require reporting on all performance metrics and outcomes necessary to inform senior officials about the outstanding portfolio and conduct risk management functions, as well as information about contractor practices.

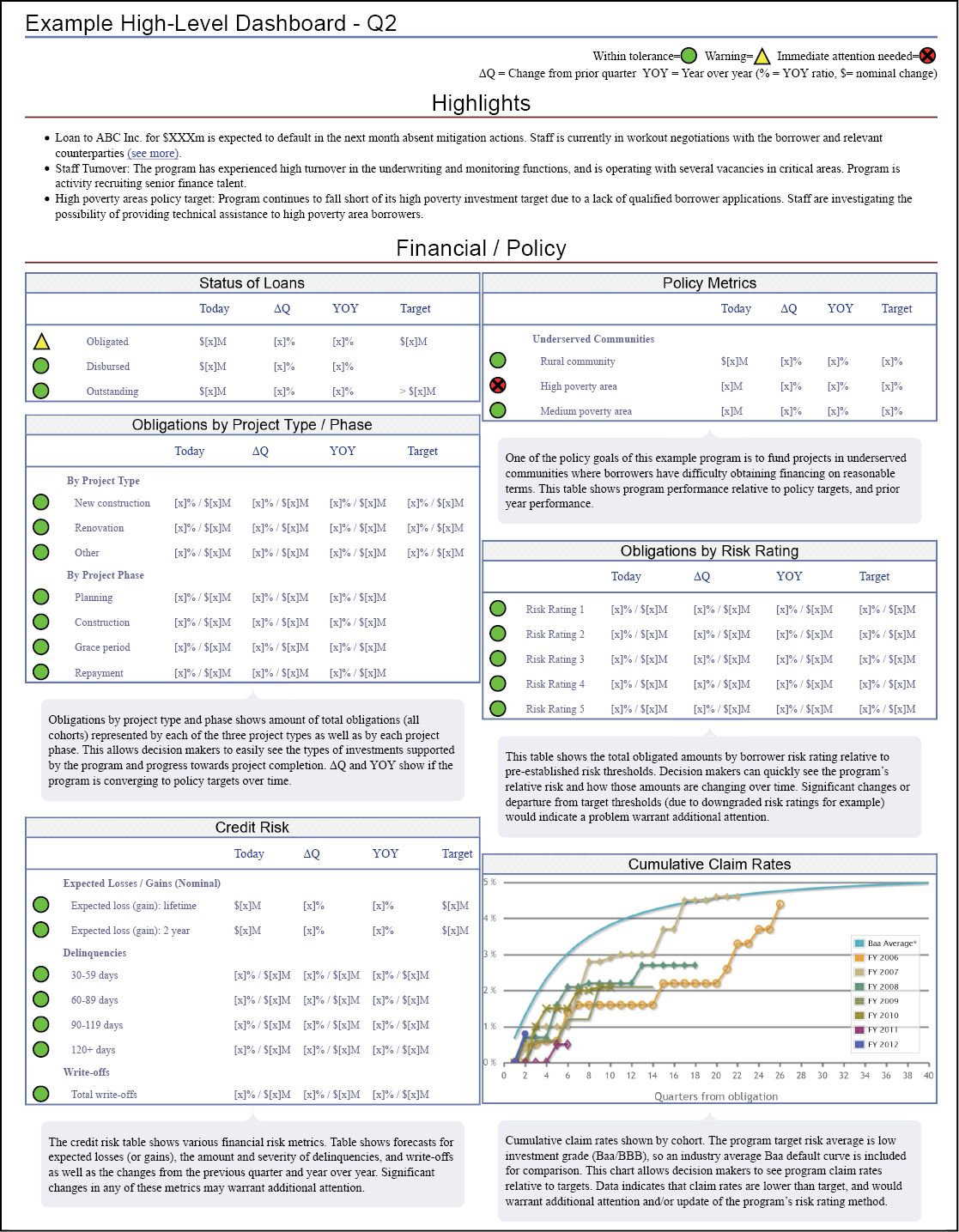

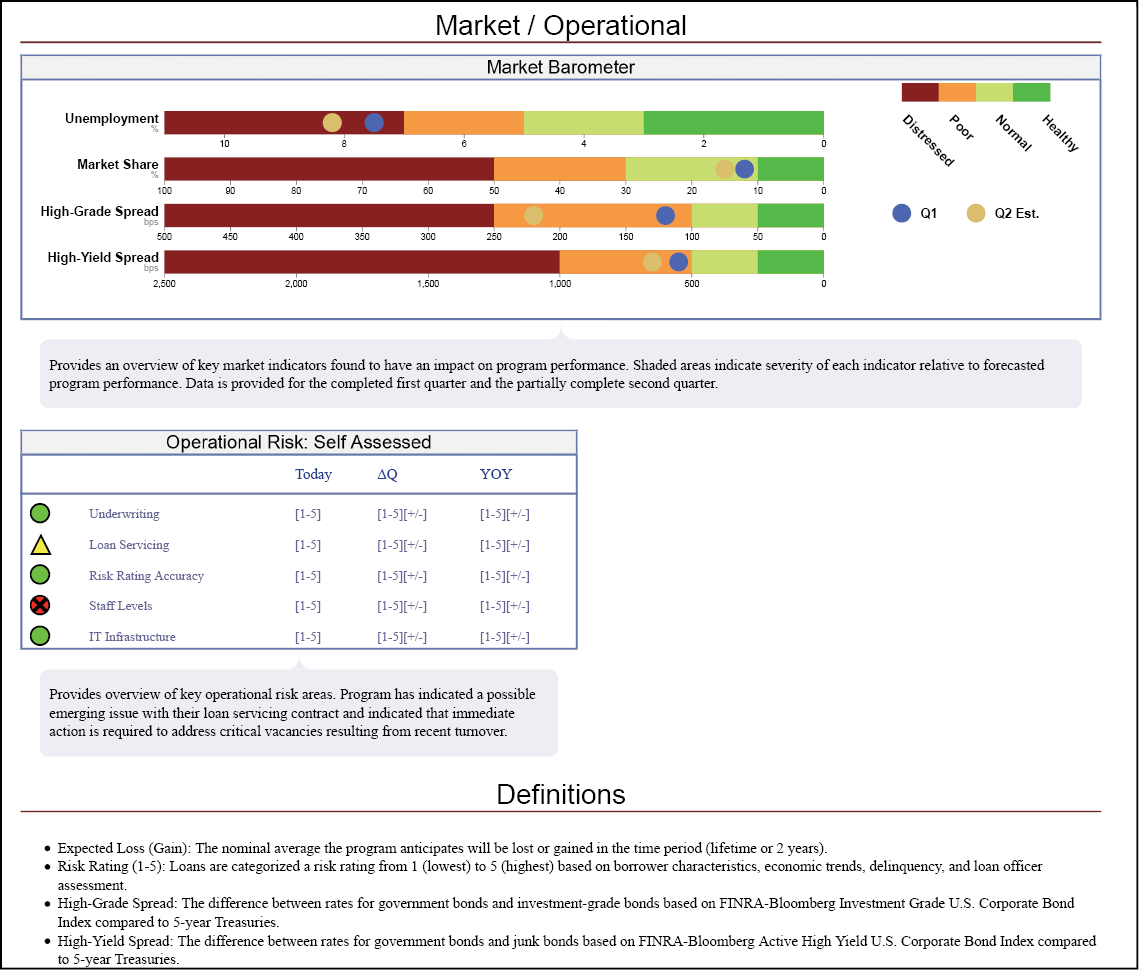

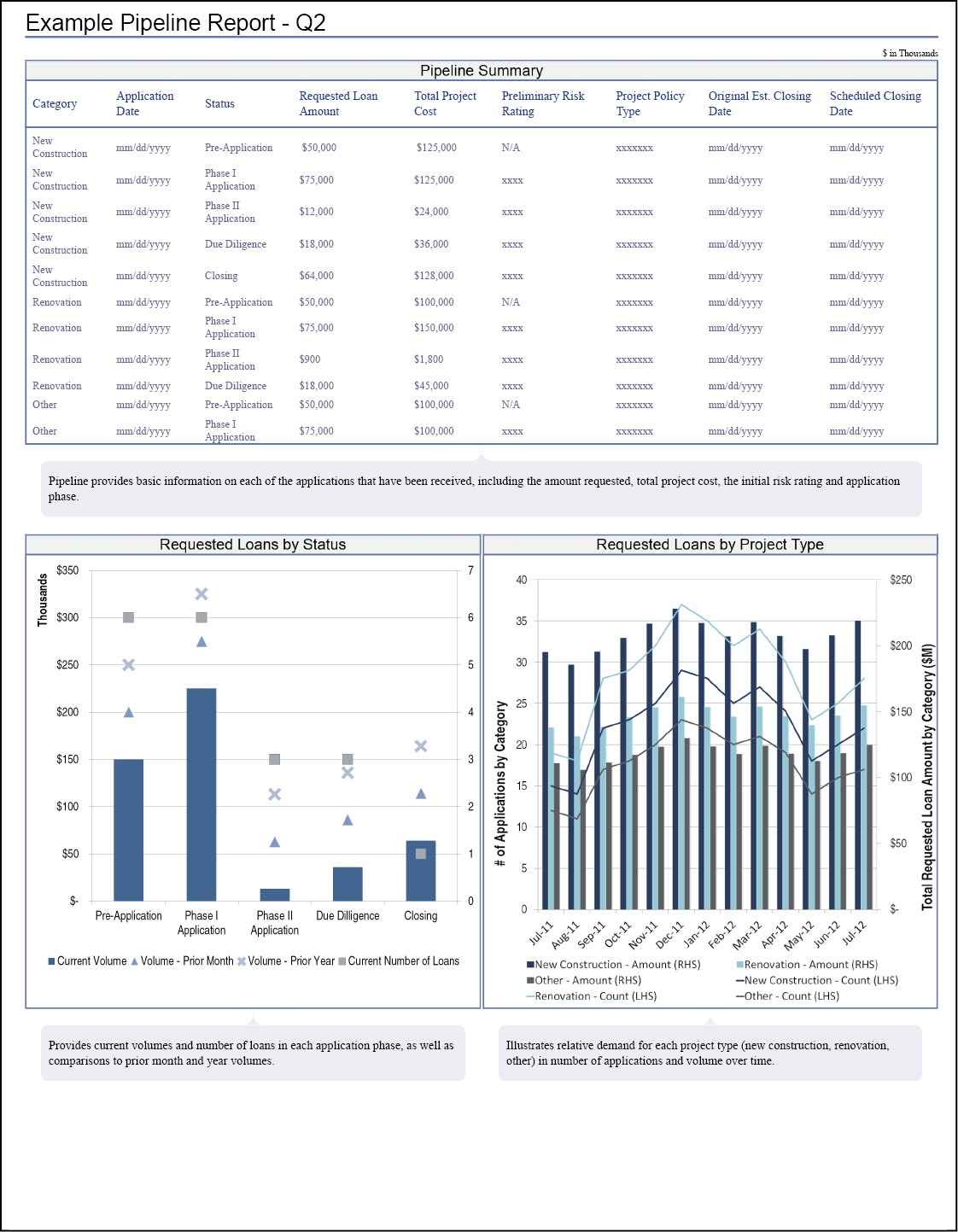

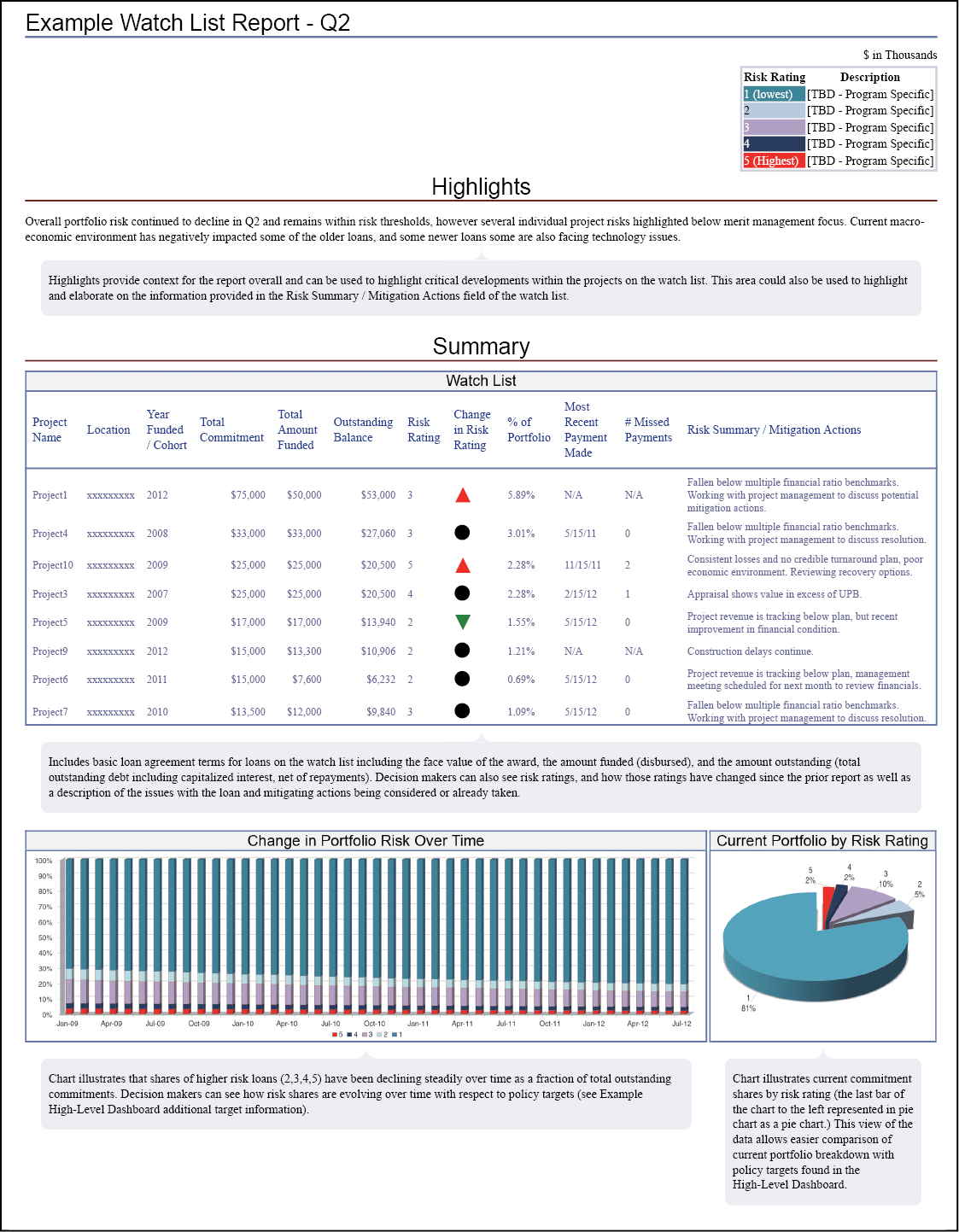

2. Data-Driven Decision Making. Agencies must have monitoring, diagnostic, and reporting mechanisms in place to provide senior-level policy officials and credit program managers a clear understanding of a program’s performance. Such mechanisms should include regular collections, analysis, and reporting of key information and trends, and also be sufficiently flexible to deliver any analysis necessary to identify and respond appropriately to any developing issues in the portfolio. Ensuring that both policy officials and program managers have a feedback loop into program performance will enable agencies to focus attention on delivering program results in the most effective and efficient ways. Reporting parameters, including the timing and form for reporting to OMB, should be coordinated with OMB, and reviewed periodically to identify any needed updates to capture relevant information and program changes.

a. Timely Reporting. High-level credit performance data should be supplied to the appropriate senior-level official and the OMB examiner with primary responsibility for the program in the form of a dashboard, or similarly high-level report, on at least a quarterly basis, or other schedule agreeable to the relevant senior official or OMB, as appropriate. Agencies should also produce lists that highlight potential loans or types of loans that may warrant additional management oversight for senior management.

b. Appropriate Report Types. Depending on the program, reporting documents should include pipeline reports, portfolio dashboards, watch lists, internal operations, reporting and lender monitoring (for guaranteed programs).

C. Management of Guaranteed Loan Lenders and Servicers.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Guidance |

Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables |

1. Lender and Servicer Eligibility.

a. Participation Criteria. Federal credit granting agencies shall establish and publish in the Federal Register specific eligibility criteria for lender or servicer participation in Federal credit programs. These criteria should include:

i. Requirements that the lender or servicer is not currently debarred/suspended from participation in a Government contract or delinquent on a Government debt;

ii. Qualification requirements for principal officers and staff of the lender or servicer;

iii. Fidelity/surety bonding and/or errors and omissions insurance with the Federal Government as a loss payee, where appropriate, for new or non-regulated lenders or lenders with questionable performance under Federal guarantee programs; and

iv. Financial and capital requirements for lenders not regulated by a Federal financial institution regulatory agency, including minimum net worth requirements based on business volume.

b. Review of Eligibility. Agencies shall review and document a lender’s or servicer’s eligibility for continued participation in a Federal credit program at least every two years. Ideally, these reviews should be conducted in conjunction with on-site reviews of lender or servicer operations (see Section III.C.3) or other required reviews, such as renewal of a lender or servicing agreement (see Section III.C.2). Lenders or servicers not meeting standards for continued participation should be decertified. In addition to the participation criteria above, agencies should consider lender or servicer performance as a critical factor in determining continued eligibility for participation.

c. Fees. When authorized and appropriated for such purposes, agencies should assess non-refundable fees to defray the costs of determining and reviewing lender or servicer eligibility.

d. Decertification. Agencies should establish specific procedures to decertify lenders, end servicing contracts, or take other appropriate action any time there is:

i. Significant and/or continuing non-conformance with agency standards; and/or

ii. Failure to meet financial and capital requirements or other eligibility criteria.

Agency procedures should define the process and establish timetables by which decertified lenders or former servicers can apply for reinstatement of eligibility for Federal credit programs.

e. Loan Servicers. Lenders or agencies transferring and/or assigning the right to service loans to a loan servicer should use only servicers meeting applicable standards set by the Federal agency. Where appropriate, agencies may adopt standards for loan servicers established by a Government Sponsored Enterprise (GSE) or a similar organization (e.g., Government National Mortgage Association for single family mortgages) and/or may authorize lenders to use servicers that have been approved by a GSE or similar organization.

2. Agreements. Agencies should enter into written agreements with lenders that have been determined to be eligible for participation in a guaranteed loan program. Lender agreements and servicing contracts should incorporate general participation requirements, performance standards and other applicable requirements of this Circular. Agencies are encouraged, where not prohibited by authorizing legislation, to set a fixed duration for the agreement to ensure a formal review of the lender or servicer eligibility for continued participation in the program.

a. General Participation Requirements. Lender agreements should include:

i. Requirements for lender or servicer eligibility, including participation criteria, eligibility reviews, fees, reporting, and decertification (see Section III.C.1, above);

ii. Agency and lender responsibilities for sharing the risk of loan defaults (see Section II.C.1.a); and, where feasible

iii. Maximum delinquency, default and claims rates for lenders or servicers, taking into account individual program characteristics.

b. Lender Performance Standards. Agencies should include due diligence requirements for originating, servicing, and collecting loans in their lender agreements. This may be accomplished by referencing agency regulations or guidelines. Examples of due diligence standards include collection procedures for past due accounts, delinquent debtor counseling procedures and litigation to enforce loan contracts.

Agencies should ensure, through the claims review process, that lenders have met these standards prior to making a claim payment. Agencies should reduce claim amounts or reject claims for lender non-performance.

c. Reporting Requirements. Federal credit granting agencies should require certain data to monitor the health of their credit portfolios, track and evaluate lender and servicer performance, and satisfy OMB, Treasury, and other reporting requirements which include the Treasury Report on Receivables (TROR). Examples of the data that agencies must maintain include:

i. Activity Indicators. Number and amount of outstanding loans at the beginning and end of the reporting period and the agency share of risk in the case of a guaranteed loan; number and amount of loans made during the reporting period; and number and amount of loans terminated during the period.

ii. Status Indicators. A schedule showing the number and amount of past due loans by “age” of the delinquency, and the number and amount of loans in default, foreclosure or liquidation (when the lender is responsible for such activities).

Agencies may have several sources for such data, but some or all of the information may best be obtained from lenders and servicers. Lender agreements should require lenders to report necessary information frequently, but at a minimum on a monthly basis (or other reporting period based on the level of lending and payment activity).

d. Loan Servicers. Lender agreements must specify that loan servicers must meet applicable participation requirements and performance standards. The agreement should also specify that servicers acquiring loans must provide any information necessary for the lender to comply with reporting requirements to the agency. Servicers may not resell the loans except to qualified servicers.

3. Lender and Servicer Reviews. To evaluate and enforce lender and servicer performance, agencies should conduct on-site reviews, prioritizing such reviews based on performance and exposure. Agencies should summarize review findings in written reports with recommended corrective actions and submit them to agency review boards. (See Section I.D.8.)

Reviews should be conducted biennially where possible; however, agencies should conduct annual on-site reviews of all lenders and servicers with substantial loan volume or whose:

a. Financial performance measures indicate a deterioration in their credit portfolio;

b. Portfolio has a high level of delinquency or default for loans less than one year old;

c. Overall default or delinquency rates rise above acceptable levels; or

d. Poor performance results in payment collections, including monetary penalties, or an abnormally high number of reduced or rejected claims.

Agencies are encouraged to develop a lender/servicer classification system, which assigns a risk rating based on the above factors. This risk rating can be used to establish priorities for on-site reviews and monitor the effectiveness of required corrective actions.

Reviews should be conducted by agency program compliance staff, Inspector General staff, and/or independent auditors. Where possible, agencies with similar programs should coordinate their reviews to minimize the burden on lenders/servicers and maximize use of scarce resources. Agencies should also utilize the monitoring efforts of GSEs and similar organizations for guaranteed loans that have been “pooled.”

4. Corrective Actions. If a review indicates that the lender/servicer is not in conformance with all program requirements, agencies should determine the seriousness of the problem. For minor non-compliance, agencies and the lender or servicer should agree on corrective actions. However, agencies should establish penalties for more serious and frequent offenses. Penalties may include loss of guarantees, reprimands, probation, suspension, and decertification.

IV. MANAGING THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT’S RECEIVABLES

Agencies must service and collect debts, including defaulted guaranteed loans they have acquired, in a manner that best protects the value of the assets. Mechanisms must be in place to collect and record payments and provide accounting and management information for effective stewardship. Agencies should collect data on the status of their portfolios on a monthly basis although they are only required to report quarterly. These servicing activities can be carried out by the agency, or by third parties (such as private lenders or guaranty agencies), or a contract with a private sector firm. Unless otherwise exempt, the DCIA, codified at 31 U.S.C. § 3711, requires Federal agencies to transfer any non-tax debt which is over 180 days delinquent to Treasury/FMS for debt collection action (31 C.F.R. Part 285). Agencies may refer debts that are less than 180 days delinquent. Under certain conditions, it may be advantageous to sell loans or other debts to avoid the necessity of debt servicing.

A. Accounting and Financial Reporting.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA), 2 U.S.C. § 661 Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA); 31 U.S.C. § 3711, 3719 Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) |

|

Regulatory |

|

|

Guidance |

Instructions for the Treasury Report on Receivables (TROR) Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board: Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards No. 2 Accounting for Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees, as amended; Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards No. 18 Amendments to Accounting Standards for Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees; and Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards No. 19 Technical Amendments to Accounting Standards for Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees in Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards No. 2. |

1. Accounting and Financial Reporting Systems. Agencies shall establish accounting and financial reporting systems to meet the standards provided in this Circular, OMB Circular No. A-127 Financial Management Systems and other Government-wide requirements. These systems shall be capable of accounting for obligations and outlays and of meeting the reporting requirements of OMB and Treasury, including those associated with FCRA and the CFO Act.

2. Agency Reports. Agencies should use comprehensive reports on the status of loan portfolios and receivables to evaluate effectiveness, to support proactive management of the program portfolio, and to enable data-driven decision making.

Agencies shall prepare, in accordance with the CFO Act and OMB guidance, annual financial statements that include information about loan programs and other receivables. Agencies should also collect data for program performance measures, including both measures of programmatic effectiveness in achieving its policy goals, and financial performance measures such as the rate of loan principal repayment, delinquency rates, default rates, recovery rates, comparisons of actual to expected subsidy costs, and administrative costs, consistent with the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010 and FCRA.

Agencies are also required to report quarterly to Treasury on the status and condition of their non-tax delinquent portfolio on the TROR. Due to a timing difference between the submissions of fiscal year-end data for the TROR, and data used for agency financial statements, the data in these two reports may not be identical. Agencies should be able to explain and reconcile any differences between the two reports.

B. Loan Servicing Requirements. Agency servicing requirements, whether performed in-house or by another agency or private sector firm, must meet the standards described below and in Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA); 31 U.S.C. § 3711 |

|

Guidance |

Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables, and Guide to the Federal Credit Bureau Program |

1. Documentation. Approved loan files (or other systems of records) shall contain adequate and up-to-date information reflecting terms and conditions of the loan, payment history, including occurrences of delinquencies and defaults, and any subsequent loan actions which result in payment deferrals, refinancing, or rescheduling.

2. Billing and Collections. Agencies shall ensure that there is routine invoicing of payments and that efficient mechanisms are in place to collect and record payments. When making payments and where appropriate, borrowers should be encouraged to use agency systems established by Treasury that collect payments electronically, such as pre-authorized debits and credit cards.

3. Escrow Accounts. Agency servicing systems must process tax and insurance deposits for housing and other long-term real estate loans through escrow accounts. Agencies should establish escrow accounts at the time of loan origination and payments for housing and other long-term real estate loans through an escrow account.

4. Referring Account Information to Credit Reporting Agencies. Agency servicing systems must be able to identify and refer debts to credit bureaus in accordance with the requirements of 31 U.S.C. § 3711. Agencies shall refer all non-tax, non-tariff commercial accounts (current and delinquent) and all delinquent non-tariff and non-tax consumer accounts. Agencies may report current consumer debts as well and are encouraged to do so. The reporting of current data (in addition to any delinquencies) provides a truer picture of indebtedness while simultaneously reflecting accounts that the borrower has maintained in good standing. There is no minimum dollar threshold, e.g., accounts (debts) owed for as low as $5 may be referred to credit reporting agencies. Agencies shall require lenders participating in Federal credit programs to provide information relating to the extension of credit to consumer or commercial credit reporting agencies, as appropriate. For additional information, agencies should refer to Treasury/FMS Guide to the Federal Credit Bureau Program.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA), 2 U.S.C. § 661 Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA), Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA), 31 U.S.C. § 3711 |

|

Guidance |

OMB Circular No. A-11, Part 5 |

1. The DCIA, authorizes agencies to sell any non-tax debt owed to the United States that is more than 90 days delinquent, subject to the provisions of FCRA. The Administration’s budget policy is that agencies are required to sell any non-tax debts that are delinquent for more than one year for which collection action has been terminated, if the Secretary of the Treasury determines that the sale is in the best interest of the United States Government. Agencies are required to sell the debts for cash or a combination of cash and profit participation, if such an arrangement is more advantageous to the Government, and make the sales without recourse. Loan sales should result in shifting agency staff resources from servicing to mission critical functions.

Beginning in FY 2000, for programs with $100 million in assets (unpaid principal balance) that are delinquent for more than two years, the agency is expected to dispose of such assets expeditiously. Agencies may request from OMB, an exception for the following:

a. Loans to foreign countries and entities;

b. Loans in structured forbearance, when conversion to repayment status is expected within 24 months or after statutory requirements are met;

c. Loans that are written off as unenforceable e.g., due to death, disability, or bankruptcy;

d. Loans that have been submitted to Treasury for collection, including collection by offset, and are expected to be extinguished within three (3) years;

e. Loans in adjudication or foreclosure; and

f. Student loans.

Agencies shall provide to OMB an annual list of loans that are exempted.

2. Evaluate Asset Portfolio. On an annual basis, agencies shall take steps to evaluate and analyze existing asset portfolios and programs associated therewith, to determine if there are avenues to:

a. Improve Credit Management and Recoveries. Improvement in current management, performance, and recoveries of asset portfolios shall be reviewed against current marketplace practices.

b. Realize Administrative Savings. Analyses of current asset portfolio practices shall include the benefit of transferring all or some portion of the portfolio to the private sector. Agencies shall develop a staffing utilization plan to ensure that when asset sales result in a decreased workload, staff are shifted to priority workload mission critical functions.

c. Initiate Prepayment. Agencies shall initiate prepayment programs when statutorily mandated or, if upon analysis of an existing asset portfolio practice, it is deemed appropriate. Prepayment programs may be initiated without the approval of OMB. Delinquent borrowers may participate in a prepayment program only if past due principal, interest, and charges are paid in full prior to their request to prepay the balance owed.

3. Financial Asset Services. Agencies shall engage the services of outside contractors as deemed necessary to assist in their asset resolution programs. Contractors providing various types of asset services are available through the General Services Administration’s Multiple Award Schedule for Financial Asset Services as follows:

a. Program Financial Advisors;

b. Transaction Specialists;

c. Due Diligence Contractors;

d. Loan Service/Asset Managers; and

e. Equity Monitors/Transaction Assistants.

4. Loan Prepayments and Loan Asset Sales Guidelines. OMB and Treasury jointly will update existing guidelines and procedures to implement loan prepayment and loan asset sales. In accordance with the agreed upon procedures, agencies conducting such prepayment and loan asset sales programs will consult with both OMB and Treasury throughout the prepayment and loan asset sales processes to ensure consistency with the agreed upon policies and guidelines. Unless an agency can document from its past experience that the sale of certain types of loan assets is not economically viable, a financial advisor shall be engaged by each agency to conduct a portfolio valuation and to compare pricing options for a proposed prepayment plan or loan asset sale. Based on the financial advisor’s report, the agencies will develop a prepayment or loan asset sales schedule and plan, including an analysis of the pricing option selected. As part of the ongoing consultation between OMB, Treasury, and the agencies, prior to proceeding with their prepayment or loan asset sales, the agencies will submit their final prepayment or loan asset sales plans and proposed pricing options to OMB and Treasury for review in order to ensure that any undue cost to the Government or additional subsidy to the borrower is avoided. The agency Chief Financial Officer will certify that an agency loan prepayment and loan asset sales program is in compliance with the agreed upon guidelines. See Part 5 of OMB Circular No. A-11.

A. Standards for Defining Delinquent and Defaulted Debt.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA), 31 U.S.C. § 3701, 3711-3720E |

|

Regulatory |

|

|

Guidance |

Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables |

Agencies shall have a fair but aggressive program to recover delinquent debt, including defaulted guaranteed loans acquired by the Federal Government. Each agency will establish a collection strategy consistent with its statutory authority that seeks to return the debtor to a current payment status or, failing that, maximize collection on the debt.

The Federal Claims Collections Standards define delinquent debt in general terms. Agency regulations may further define delinquency to meet specific types of debt or program requirements.

1. Direct Loans. Agencies shall consider a direct loan account to be delinquent if a payment has not been made by the date specified in the agreement or instrument (including a post-delinquency payment agreement), unless other satisfactory payment arrangements have been made.

2. Guaranteed Loans. Loans guaranteed or insured by the Federal Government are in default when the borrower breaches the loan agreement with the private sector lender. A default to the Federal Government occurs when the Federal credit granting agency repurchases the loan, pays a loss claim or pays reinsurance on the loan. Prior to establishing a receivable on the agency financial records, each agency must consider statutory and regulatory authority applicable to the debt in order to determine if the agency has a legal right to subject the debt to the collection provisions of this Circular.

3. Other Debt. Overpayments to contractors, grantees, employees, and beneficiaries; fines; fees; penalties; and other debts are delinquent when the debtor does not pay or resolve the debt by the date specified in the agency’s initial written demand for payment (which generally should be within 30 days from the date the agency mailed notification of the debt to the debtor).

B. Administrative Collection of Debts.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA), 31 U.S.C. § 3701, 3711-3720E |

|

Regulatory |

26 C.F.R. 301.6402-1 through 7 Federal Claims Collections Standards |

|

Guidance |

Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables, Cross-servicing/offset guidance documents, and Guide to the Federal Credit Bureau Program |

Agencies shall promptly act on the collection of delinquent debts, using all available collection tools to maximize collections. Agencies shall transfer debts delinquent 180 days or more to the Treasury/FMS or Treasury-designated debt collection centers for further collection actions and resolution, and are strongly encouraged to transfer debts that are less than 180 days delinquent in cases where it is anticipated to improve collectability, and would be consistent with program policy goals and other requirements. Exceptions to this requirement (e.g., the debt has been referred for litigation) can be found in 31 U.S.C.§ 3711 and 31 C.F.R. Part 285.12(d).

1. Collection Strategy. Agencies shall maintain an accurate and timely reporting system to identify and monitor delinquent receivables. Each agency shall develop a systematic process for the collection of delinquent accounts. Collection strategies shall take full advantage of available collection tools while recognizing program needs and statutory authority.

2. Collection Tools for Debts Less than 180 Days Delinquent. Agencies may use the following collection tools when the debt is fewer than 180 days delinquent:

a. Demand Letters. As soon as an account becomes delinquent, agencies should send demand letters to the debtor. The demand letter must give the debtor notice of each form of collection action and type of financial penalty the agency plans to use, including all required notifications for referral to cross-servicing and the Treasury Offset Program (TOP). Additional demand letters may be sent if necessary. See 31 U.S.C. § 3711, and 31 C.F.R. Parts 285 and 901.2

For consumer accounts, the first demand letter or initial billing notice should include the 60 day notification requirement of the agency’s intent to refer to a credit bureau. Once the 60 day period has passed, the agency should initiate reporting if the account has not been resolved. This will also enable uninterrupted reporting to credit bureaus by cross-servicing agencies. The 60 day notification of intent to refer to a credit bureau is not required for commercial accounts (or accounts with state, tribal, or local governments) (See Treasury/FMS Guide to the Federal Credit Bureau Program).

b. Internal Offset. If the agency that is owed the debt also makes payments to the debtor, the agency may use internal offset to the extent permitted by that agency’s statutes and regulations and the common law. Delinquent debts owed by an agency’s employees may be offset in accordance with statutes and regulations administered by the Office of Personnel Management. (See OPM regulations and statutes.)

c. Treasury Offset Program (TOP). Agencies may collect delinquent debt, which is less than 180 days delinquent, by referring those debts to Treasury/FMS in order to offset Federal payments due to the debtor. Payments which Treasury will offset include certain benefit payments, Federal retirement payments, salaries, vendor payments, tax refunds, and other Federal and State payments as allowed by law. (See 31 U.S.C. § 3716, 31 U.S.C. § 3720A, 31 C.F.R. Part 285, 26 C.F.R. 301.6402, 31 C.F.R. Chapter II, Part 901.3, and Federal Acquisition Regulations, Subpart 32.6.) If a Federal payment has not yet been initiated in TOP, agencies may request that the paying agency perform the offset.

d. Administrative Wage Garnishment. Agencies have the authority to administratively garnish the wages of delinquent debtors in order to recover delinquent debt. The maximum garnishment for any one debt is 15 percent of disposable pay. Multiple garnishments from all sources against one debtor’s wages may not exceed 25 percent of disposable pay of an individual. (See 31 U.S.C. § 3720D, 31 C.F.R. Part 285.11 and 15 U.S.C. § 1673(a)(2)).

e. Contracting with Private Collection Agencies. Treasury has contracted with private collection agencies that may be used by Federal agencies to provide assistance in the recovery of delinquent debt owed to the Government. (See 31 U.S.C. § 3711, 31 U.S.C. § 3718, 31 C.F.R. Parts 285 and 901, and Fair Debt Collection Practices Act.) Agencies may also transfer debts to Treasury prior to 180 days for the purpose of referral to private collection agencies.

f. Treasury Cross-Servicing. Agencies may transfer debts to Treasury for full servicing at any time after the due process requirements. (See 31 C.F.R. Part 285.)

3. Collection of Debts that are Over 180 Days Delinquent. This paragraph sets forth Treasury’s collection procedures for debts which are over 180 days delinquent.

a. Treasury Offset Program. The DCIA requires that all agencies recover debt delinquent more than 180 days by referring those debts to the Treasury for offset of tax refunds and other Federal payments. Agencies must refer all accounts for offset in accordance with guidance provided by the Department of the Treasury/FMS. (See Federal Claims Collection Standards, 31 U.S.C. § 3716, 31 U.S.C. § 3720A, and 31 C.F.R. Part 285.) The following types of offset are undertaken in TOP (See 31 U.S.C. § 3716, 31 U.S.C. § 3720A, 31 C.F.R. Part 285, 26 C.F.R. 301.6402, 31 C.F.R. Chapter II, Part 901.3, and Federal Acquisition Regulations, Subpart 32.6):

i. Tax Refund Offset;

ii. Vendor Offset;

iii. Federal Retirement Offset;

iv. Salary Offset;

v. Benefit Offset (includes all benefit payments incorporated into the program); and

vi. Other Federal payments as allowed by law (as such payments are allowed into the program).

b. Cross-Servicing. The DCIA requires that all debts owed to agencies which are more than 180 days delinquent shall be transferred to Treasury/FMS or a Treasury-designated debt collection center for servicing. The DCIA contains provisions and requirements for exempting certain classes of debts from being transferred for servicing. (See 31 U.S.C. § 3711, 31 C.F.R. Part 285, and I TFM 4-4000.) Once debts are transferred to Treasury, agencies must cease all collection activities other than maintaining accounts for TOP.

Once Treasury has received a debt for servicing, the appropriate debt collection actions will be taken. These actions may include sending demand letters; phone calls to delinquent debtors; credit bureau reporting; referring debtors to TOP; referring debtors to private collection agencies; administrative wage garnishment; and any other available debt collection tool.

C. Referrals to the Department of Justice.

1. Referral for Litigation.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Federal Debt Collection Practices Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1692, et seq. Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA), 31 U.S.C. § 3711 |

|

Regulatory |

|

|

Guidance |

Treasury/FMS Litigation Referral Process Handbook, and Managing Federal Receivables, Appendix 8 |

Agencies, including Treasury/FMS or Treasury-designated debt collection centers, shall refer delinquent accounts to the Department of Justice (DOJ), or use other litigation authority that may be available, as soon as there is sufficient reason to conclude that full or partial recovery of the debt can best be achieved through litigation. Referrals to DOJ should be made in accordance with the Federal Claims Collection Standards. If the debtor does not come forward with a voluntary payment after the claim has been referred for litigation, a lawsuit shall be initiated promptly.

a. In consultation with DOJ, agencies shall establish a system to account for: i) claims referred to DOJ, and ii) claims closed by DOJ and returned to the respective agencies.

b. Agencies shall stop the use of any collection activities including TOP and refrain from further contact with the debtor once a claim has been referred to DOJ. As part of the litigation process, DOJ will refer post-judgment debtors to TOP.

c. Agencies shall promptly notify DOJ of any payments received on a debtor’s account after referral of the claim for litigation.

d. DOJ shall account to agencies for monies or property collected on claims referred by the agencies.

2. Referral for Approval of Compromise Offer.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA), 31 U.S.C. §3711 |

|

Regulatory |

|

|

Guidance |

Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables |

Agencies may compromise a debt within their jurisdiction when the principal balance of the debt does not exceed $100,000 (or any higher amount authorized by the U.S. Attorney General). Unless otherwise provided by law, when the principal balance of the debt is greater than $100,000 (or any higher amount authorized by the U.S. Attorney General), the compromise authority rests with the Department of Justice. (See 31 C.F.R. Part 902.)

3. Referral for Approval to Terminate Collection Activity.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA), 31 U.S.C. §3711 |

|

Regulatory |

|

|

Guidance |

Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables |

Agencies may terminate collection on a debt within their jurisdiction when the principal balance of the debt does not exceed $100,000 (or any higher amount authorized by the U.S. Attorney General). Unless otherwise provided by law, when the principal balance of the debt is greater than $100,000 (or any higher amount authorized by the U.S. Attorney General), the authority to terminate rests with the Department of Justice. (See 31 C.F.R. Part 902.)

D. Interest, Penalties and Administrative Costs.

|

REFERENCES |

|

|

Statutory |

Debt Collection Act of 1982 (DCA); Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996 (DCIA), 31 U.S.C. §3717 |

|

Regulatory |

|

|

Guidance |

Treasury/FMS Managing Federal Receivables, Chapter 4 |