When I joined the White House a year ago, I asked the Archivist of the United States David Ferriero if the Declaration of Sentiments was part of the National Archives. The Declaration of Sentiments is the foundational document for women’s rights drafted in Seneca Falls, New York, at the first women's rights convention in July 1848. It changed the course of history.

Ferriero and his team asked around, and learned that it isn’t in the Archives’ holdings — the team contacted various experts and learned that the original Seneca Falls Declaration has not been found. The closest to “original” that anyone knew of is the printing of the text done in 1848 by Frederick Douglass’s print shop in Rochester. They found newspaper accounts and also checked “The Road to Seneca Falls” by Judith Wellman, who wrote that no one has ever found the minutes by Mary Ann M’Clintock that likely also went to Douglass’s print shop. They learned that the tea table upon which the original declaration was drafted has been found, but the document itself is still missing.

The road to drafting the Declaration of Sentiments started in 1840 when Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott and their husbands traveled across the Atlantic to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London only to learn that women were no longer permitted on the main floor and had to listen from a gallery. We can only imagine their frustration!

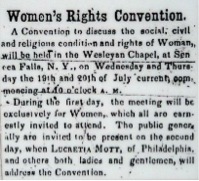

A few years later, Mott visited her cousin Katherine McClintock near Seneca Falls, New York. During the visit, they hosted a tea where five women planned a convention to discuss women’s rights. In preparation for the convention, Stanton drafted a “Declaration of Rights and Sentiments,” which she modeled after the Declaration of Independence. In the document, she called for moral, economic, and political equality for women.

Our Search for the Sentiments

While the Archivist and his team searched for the Declaration of Sentiments, we at the White House conducted a search of our own. The Women’s Rights National Historical Park at Seneca Falls said that after the convention, Frederick Douglass — one of the more than 30 men who joined the convention and signed the declaration — took it to Rochester to publish it in his newspaper The North Star, but since that time the guide said that as far as they know it has been “lost to time.” We asked several academics and historians, including teams who founded and lead our academic women’s studies programs at colleges and universities for input as we searched and also checked various popular online marketplaces in case it was for sale.

We checked in with the Library of Congress where a team searched its collection including the Elizabeth Cady Stanton papers. The Library has a version that was incorporated into the “Report of the Women’s Rights Convention, Held at Seneca Falls, N.Y., July 19th and 20th, 1848,” included in a scrapbook kept by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her daughter, Harriet Stanton Blatch. But it’s not the original.

Here’s where you come in: Let's see if we can find this thing — and unveil other untold stories and histories in the process. Call it a real-life “National Treasure,” if you like.

Have a tip or an idea as to where the sentiments might be located? Or a related story? Share that with us here, and post on your social channels using the hashtag #FindTheSentiments. Have another untold story that you want to see written into history? We want to hear those, too.

It's going to take all of us speaking up to help preserve the stories of the incredible women and men who made this country what it is today. I hope you'll add your voice to the conversation.

The Lost History: Our own “National Treasure”

I had always wanted to see the Declaration of Sentiments and wanted to begin to raise awareness about its existence, its importance, its origin story, and its content because I’ve found that most people had never heard of it, despite its important content and position in world history. Like other American children, I learned about American history in social studies classes throughout school, but they touched only briefly on a few details of the struggle for women's rights and equality.

Women’s history was viewed as a niche corner of a la carte history, rather than stories and feats that were foundational to the shaping of our nation.

Our textbooks had only a few pages with a handful of photos and mentions of names, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Jane Addams, and only a brief description of the struggle for women’s right to vote leading up to the 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and other stories in the struggle for women’s full equality.

Names like Mary Church Terrell, Ida B. Wells, and Alice Paul, as well as references to suffrage gatherings, awareness parades and protests, cross-country rallies, the multi-week 1913 suffrage walk from New Jersey to Washington, D.C., the evolving strategies to push for voting and equality at the state and Federal levels by the National Woman Suffrage Association and the National Woman’s Party, frequent jail time for hundreds of women, hunger strikes, force feeding, the brutal Night of Terror in November 1917, the first drafting of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923, and so much more, were not discussed. Women’s history was viewed as a niche corner of a la carte history, rather than stories and feats that were foundational to the shaping of our nation.

Some Americans know about the women who went to work in factories and shipyards during World War II thanks to Rosie the Riveter, and the women who kept the game of baseball going during those years from the film “A League of Their Own,” but they often don’t know Grace Hopper, the Navy Rear Admiral who was at the forefront of computer programming for nearly 50 years and invented computer languages; or NASA’s brilliant mathematician Katherine Johnson; or the University of Pennsylvania ENIAC programmers — six women who were the first digital programmers in America during WWII; or Rosie Rios, Treasurer of the United States who is working with Treasury Secretary Lew to make sure women are included on paper currency for the first time in a century. The only two women who have ever appeared on our notes were Pocahontas and Martha Washington in the 1800s.

Listen to the stories of other fascinating women in STEM.

We need to expand who is included in our well known history. It’s an honor to work for a President who has prioritized empowering women and promoting rights and progress through policy initiatives to combat discrimination, expand access to health care, support women-owned business, fight for fair pay, keep women safe from violence at home and school, and include women in all aspects of our economy, including entrepreneurship and innovation leadership opportunities. On his first day in office, the President created the White House Council on Women and Girls led by Valerie Jarrett and Tina Tchen to ensure that the needs and empowerment of women and girls are taken into account in all programs, policies, and legislation.

This conversation is just beginning.

It is not lost on me that the ongoing invisibility of women and girls is a serious issue for our country, and for the world. The invisibility of our history, heroes, stories, challenges, and success handicaps the future of all Americans, and it deeply affects our economy and our communities.

The Declaration of Sentiments can help us tell that story. I hope that one day this foundational document will have a home on display in the Rotunda of our National Archives with the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. But, even if we ultimately find that it is lost for good, my hope is that we can help bring to light the stories of heroes most of this country — and our children especially — have yet to meet. With that knowledge, the future for all men and women will be brighter.

Stay tuned — we'll be in touch with what we learn!

@USCTO @WhiteHouseOSTP #FindTheSentiments