This morning, the Council of Economic Advisers released an issue brief that highlights the challenges many American families face in providing high-quality care and education experiences for their young children. Specifically, public investments in children are lowest before age 5, precisely when many parents have the least ability to invest themselves.

Economic research has established that investments in children have large benefits for both children as well as for society as a whole. Indeed, public provision of K-12 education has long been understood as essential for promoting opportunity and for fostering a productive workforce. More recently, research has shown the critical importance of the years before children enter school. As earlier CEA work discusses, a growing body of research at the intersection of economics, neuroscience, and developmental psychology shows that changes in environment and the actions of parents and caregivers have a substantial impact on children’s future educational and economic outcomes. In turn, improvements or deficits in early investments can perpetuate themselves, in part by enhancing or reducing the efficacy of later childhood investments.

In the United States, today, however, public investments are relatively low during the first five years of a child’s life, only ramping up as they age into the K-12 educational system. Parents of the youngest children, who are typically earlier in their careers and have lower earning power, face the largest need for investment in their children when they can least afford it. The remainder of this blog describes the data and research on this issue, and is being released in conjunction with new evidence on the effectiveness of the Community Diaper Program, a collaboration between the White House and private-sector partners to increase access to diapers for low-income families. (Note: Throughout this blog post, charts are numbered as they appear in the issue brief to facilitate locating them in the full brief).

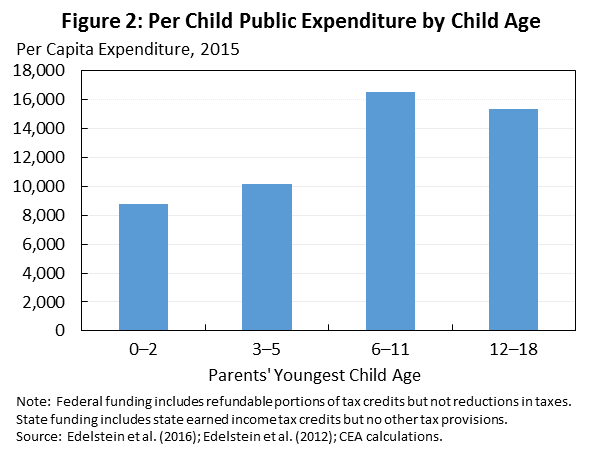

1. Existing public policies provide the smallest investments when children are youngest.

As children grow older, levels of public investments rise and the economic burden on families falls, primarily due to universal access to K-12 education. Building off of earlier analysis, CEA estimates that combined local, state, and federal annual expenditure in 2015 was 63 percent higher per child for children between 6 and 11 years old than for those just a little younger, or between 3 and 5 years old.[1] More specifically, average annual public spending per child was over $16,000 for those between 6 and 11 years, but only approximately $10,000 for those between 3 and 5 years and less than $9,000 for those 2 years or younger. Many federal, state, and local early care and education programs receive insufficient funding to cover all eligible children, leaving major gaps in access and offering opportunities for further high-return investments.

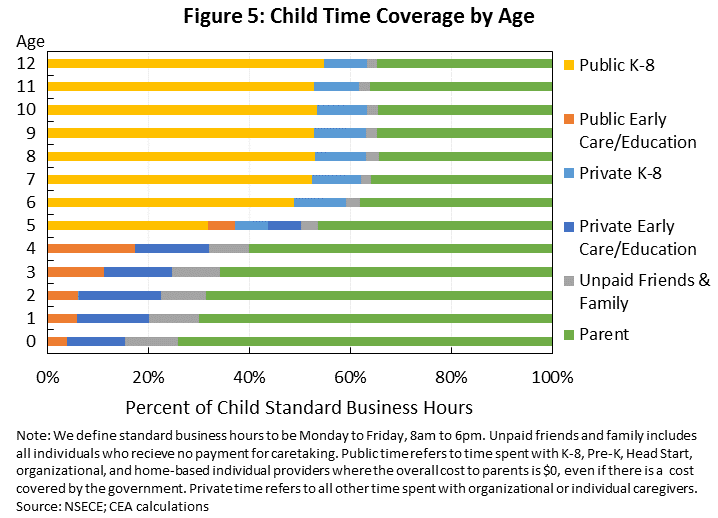

2. Publicly-financed early care and education programs provide care for only about 5 hours per week on average for children under age 5.

The National Survey of Early Care and Education provides a detailed look at where children spend their time. During standard business hours—or the 50 hours Monday through Friday between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m.—U.S. children up through age 4 are covered by publicly-financed early care and education programs for an average of only 5 hours per week, or 9 percent of this time. Families must arrange coverage of all remaining hours from their own time (68 percent of child hours); the time of unpaid friends, families, and neighbors (9 percent); and privately-paid providers (14 percent). In the earlier years especially, most children have no time covered by public programs. Even for children from low-income families—or those earning below 130 percent of the poverty line—public funding only covers an average of 6 hours per child per week. Statistics are similar for single-parent families. The burden on families lessens once children reach age 5, after which the public K-12 system covers over half of children’s standard business week hours on average.

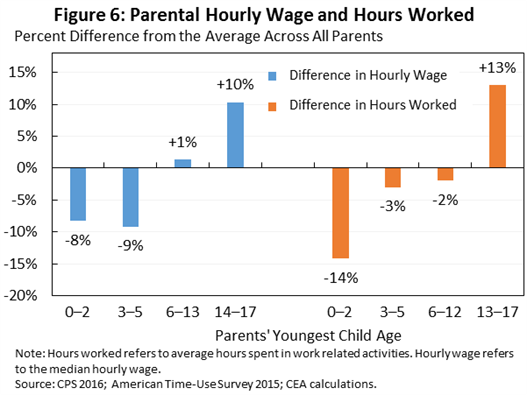

3. Parents with the youngest children have the least ability to make private investments.

Parents with younger children generally have lower earning power, as they are younger themselves and earnings tend to rise with age, and have also had fewer years to accumulate savings. Moreover, given that parents experience a larger time crunch when their children are young, they devote the fewest hours to earning in this phase. Parents who have an infant or toddler earn 8 percent less per hour and work 14 percent fewer hours than the average parent. In contrast, parents whose youngest child is over the age of 13 earn 10 percent more and work 13 percent more hours. Reflecting this disconnect between the timing of resources and responsibilities, the family poverty rate is highest—at about 15 percent—when children are youngest. It falls by almost a third as children reach older ages. Parents of young children are also 20 percentage points less likely to have a credit score above 650, making them more credit-constrained and thus less able to borrow against future income to finance investments. Economic theory and empirical analysis suggest that the inability to borrow could lead parents, especially those with lower earning power, to underinvest in children’s development. Indeed, many low-income families with young children have trouble financing even household necessities, such as diapers.

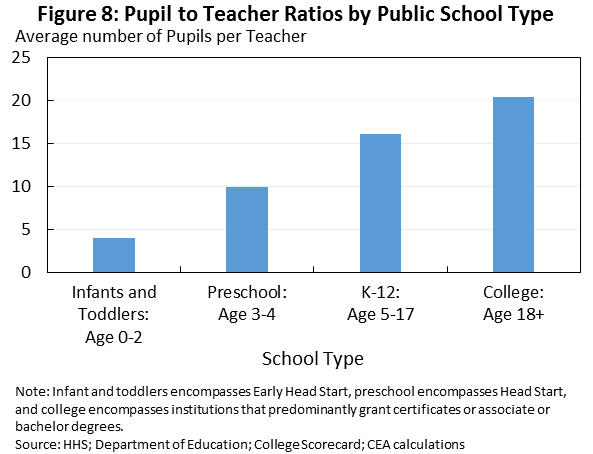

4. High-quality early care is expensive because younger children require more individualized attention.

The average cost of providing care for an infant or toddler outstrips the cost of in-state tuition at a public four-year university in many states, and is one of the highest household expenses for families with young children across the nation. The high cost of early care in part reflects the substantial and fixed resources required per child. Younger children require more individualized attention, making it hard to spread the cost of care across children. Between the ages 0 to 2, the standard in Early Head Start centers is to allow no more than 4 children per each adult, as children thrive from responsive, personal interactions with caregivers. By ages 3 to 4, Head Start centers allow up to a 10-to-1 ratio. As children grow older and become better able to attend to their own needs, this ratio can increase further. In U.S. public K-12 schools, the average student-to-teacher ratio is 16 and by college it is 20.

5. The Obama Administration has made significant progress improving access to high-quality early childhood care and education, but much work remains.

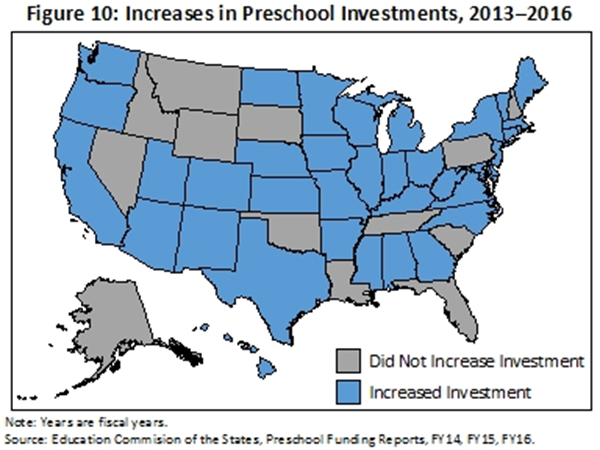

The Obama Administration has taken a range of steps over the past eight years to help ensure that America’s children have access to healthy, enriching early experiences. Overall, the Administration has increased investments by over $6 billion in early childhood programs from fiscal years 2009 to 2016, including increasing access to high-quality preschool, Head Start, Early Head Start, child care subsidies, evidence-based voluntary home visiting, and programs for infants and toddlers with disabilities. A large component of the President’s early learning initiative has been his call for a new federal-state partnership to provide access to high-quality preschool for all children. When the President made his call to action during his 2013 State of the Union, 40 states offered preschool. Now all but four do, and 38 states including DC have increased their investment in preschool by $1.5 billion between fiscal years 2013 to 2016. For younger children, the President has also called for access to affordable, quality child care for every working and middle-class family. Finally, the President has worked to strengthen the safety net for low-income families and help parents balance their work and family responsibilities, such as through income transfers, in-kind transfers, and paid sick and family leave.

Despite these improvements, much work remains to ensure all children receive the care, education, and economic opportunities they deserve. Indeed, relative to other advanced nations, the United States spends relatively little on early childhood education. The US ranked 33rd out of 36 nations in total investment in early childhood education relative to country wealth in 2011, only spending 0.4 percent of GDP compared to the OECD average of 0.8 percent.

[1] This analysis was based on analysis by Edelstein et al. (2016) and Edelstein et al. (2012) that reviewed over 100 state and federal programs, including the federal Child Tax Credit; standard income tax dependent exemption; Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children program; Supplemental Nutrition and Assistance Program; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families programs; Child Care and Development Block Grant; Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program; Individuals with Disabilities Act; Head Start; Title I: Education for the Disadvantaged program; Social Security; state and federal Medicaid; state and federal Earned Income Tax Credit; and federal, state and local spending on PK-12 schools. Billen et al. (2007), Edelstein et al. (2012), and Edelstein et al. (2016) contain more detailed breakouts by program.

Sandra Black is a Member of the Council of Economic Advisers.