U.S. lands provide us with a wide array of benefits including food, clothing, wood products, living space, wildlife habitat, recreation, clean air, and clean water. They also play a key role in meeting our climate targets under the Paris Agreement. That is why, under the President’s Climate Action Plan, the Administration has prioritized improving our understanding of U.S. lands’ capacity to store carbon and implemented programs such as the USDA Building Blocks for Climate Smart Agriculture and Forestry to bolster that capacity.

Our most recent GHG Inventory shows U.S. lands sequestering 11 percent of economy-wide emissions, a contribution that will become even more significant as reductions are achieved elsewhere in the economy. The U.S. Second Biennial Report shows that land carbon sequestration plays an important role in meeting our 2025 Paris Agreement target to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by 26-28 percent, with our forests potentially offsetting 14-18 percent of our emissions in that year. Finding further opportunities for sequestering carbon in the land sector to deliver large-scale “negative emissions” will be vital to a cost-effective climate strategy.

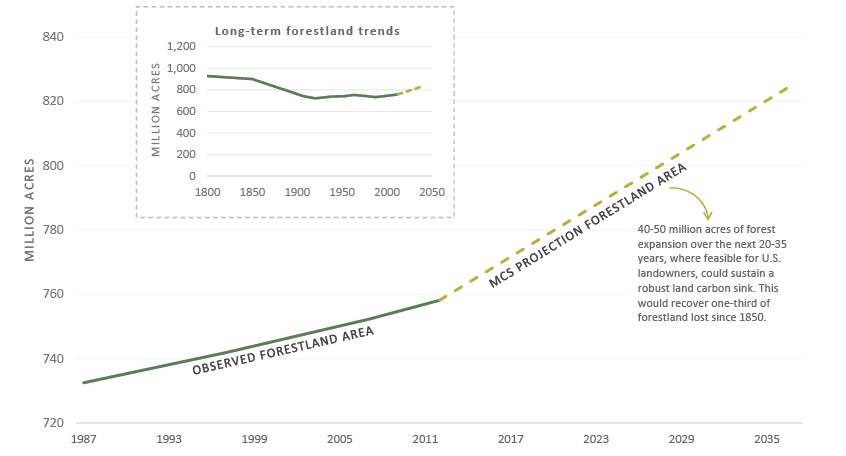

The Mid-Century Strategy (MCS), released earlier this month as a key Paris Agreement deliverable, shows pathways for deeper reductions in net U.S. economy-wide emissions by 2050. In these scenarios, our forests and soils have the potential to offset up to 45 percent of our remaining mid-century emissions. Expanding forests by 40-50 million acres over the next 20-35 years would put us on track to achieve this outcome (see figure below).

Moreover, the MCS affirms that there is major potential to generate biomass on our working agricultural and forest lands for low-carbon bioenergy even while we continue to increase the carbon stored in forests and other landscapes. A flexible energy source, biomass can be processed as liquid, solid, or gas, and in many instances can readily displace fossil fuels without significant infrastructure changes. Since biomass combustion emits CO2, it can also be paired with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies, creating additional potential for scalable “negative emissions” that could offset an additional 22 percent of our emissions by 2050 beyond what our forests and soils directly absorb. With these assumptions, overall biomass use in 2050 more than doubles from current levels across the scenarios considered in the MCS.

The good news for U.S. farmers, ranchers, and forest owners is that future climate policy can bolster bioenergy markets and support financial incentives for additional land carbon storage, creating new revenue streams for land owners and bolstering economic vitality in rural communities. Bioenergy markets also have the potential to drive investment in forests and additional tree planting as indicated in a number of studies. We encourage further work to quantify and better understand this dynamic in the MCS.

We will need to ensure that increasing biomass usage complements broader efforts to promote robust carbon storage in our forests and soils. To ensure that these emerging incentives and markets are all working in concert, while also increasing output of other land-based goods and services like food production, accurate carbon accounting tools for assessing net carbon changes in forests and other landscapes are necessary. These tools use the latest science and data to calculate net carbon effects from a variety of land-based activities, allowing for consistently and reliably estimating net carbon benefits. Examples of these tools are discussed in the MCS.

Failing to use the latest science to underpin these accounting tools risks making our overall climate efforts inefficient and potentially counter-productive. As we look to achieve ambitious long-term emissions reduction goals, we will want to target the biggest bang-for-the-buck carbon-reducing opportunities across U.S. landscapes, whether through carbon sequestration or carbon-beneficial forms of biomass.

New policies and programs that reward emissions reductions and carbon sequestration will of course be critical to achieving deeper emissions reductions. Experience generated by ongoing federal, state, university, and stakeholder research and demonstration projects is essential to laying the groundwork for such program design. The option for States to use biomass under EPA's Clean Power Plan, for example, was designed to generate such experience and advance the program and policy development effort.

For these reasons, and consistent with previously stated positions, the Administration objects to any legislation that represents biomass as categorically “carbon-neutral.” There are circumstances in which biomass is grown, harvested and combusted in a carbon neutral fashion but carbon neutrality is not an appropriate a priori assumption; it is a conclusion that should be reached only after considering a particular feedstock’s production and consumption cycle. Legislation is not an appropriate tool for defining the details of the science-based, flexible tools and programs needed to reliably ensure climate benefits, accounting for changes in landscapes over time, market feedback effects, and the varying ability of landowners to manage landscapes to achieve increased carbon storage along with biomass production. Developing the appropriate methodological frameworks that allow us to estimate the net landscape carbon effects of diverse biomass sources is an important enabling component of effective bioenergy policy. This requires analyzing the most current data and modeling while ensuring ongoing coordination across many stakeholders. These frameworks also need the flexibility to evolve over time with the latest science and changing landscapes. There is no short cut to establishing the critical feature of a successful bioenergy strategy - putting in place policies and programs that are carefully designed to rigorously distinguish and reward the kinds of activities and investments that result in clear-cut atmospheric benefits.

Continuing to invest, through a variety of strategies, in U.S. landscapes can generate dividends across climate, economic, and conservation objectives. Moving forward in alignment with the evolving science and a deeper understanding of effective program and policy options will help ensure we meet our near- and long-term emissions reduction targets while benefitting U.S. landowners and the American public.