By Chad Maisel

In remote Washington County, Maine, low-income parents are enrolling in a family studies program at the local university, while their children participate in child care at co-located Head Start centers.

Sixteen hundred miles away, the White Earth Nation in Northern Minnesota has created a universal intake system that allows families to access a host of essential programs and services through a “no wrong door” approach.

And in Appalachian Maryland, Garrett and Allegany Counties are breaking down agency siloes and bundling services, from financial management to child care to career training, to reduce child poverty and improve whole-family outcomes.

While concepts like “universal intake,” “comprehensive referral networks,” and “colocation of services” may not grab headlines, in many cases, they represent essential strategies to help entire families—not just kids or their parents—rise up to the middle class. Across the country, communities have recognized the promise of a “two-generation approach”—intentionally linking, coordinating, and aligning high-quality services for children with high-quality services and supports for their parents to maximize the impact of disparate programs.

Two-generation strategies have gained traction out of recognition that despite our best efforts, we don’t always get the best outcomes for our children. Essential health, education, and workforce programs are often structured to serve either adults or children, rather than focusing on the entire family together. However, we cannot maximize the impact of high quality early childhood education if the child returns home to an unemployed parent and lacks access to healthcare, safe housing, and other key services. And with more than one in four college students today with children of their own, we cannot expect student parents to be successful without high-quality child care. In rural areas, two-generation approaches that co-locate services may be particularly impactful, given the long distance families must travel to reach essential programs and services and stretched capacity of many rural service agencies.

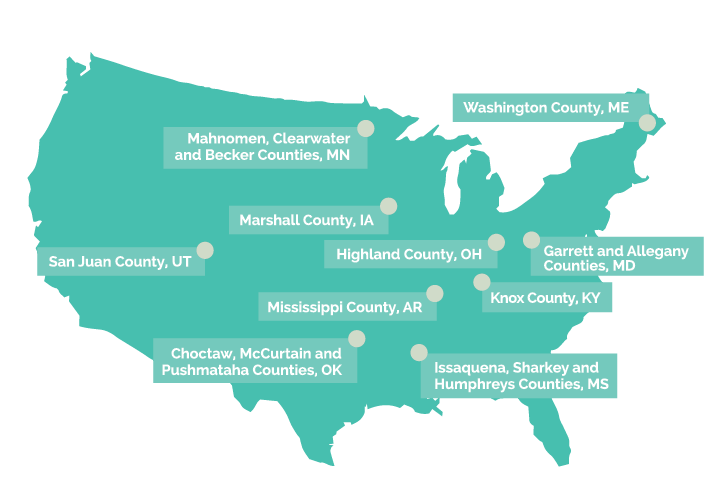

That’s why last year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched the Rural Integration Models for Parents and Children to Thrive (Rural IMPACT) Demonstration, a cross-agency effort to combat poverty and improve upward mobility in rural and tribal places. The demonstration provides 10 pilot communities with targeted technical assistance, local capacity, and access to a “barrier-breaking” Federal policy team, to help adopt a two-generation approach to programs, policies, and systems, and better meet the needs of low-income kids and parents. In places like Machias, White Earth, and Garrett County, they are already making remarkable progress.

We know that countless other communities can learn from the pioneering Rural IMPACT demonstration sites. It’s why today, at the Rural IMPACT White House Symposium, HHS is releasing a new report, Implementation of the Federal Rural IMPACT Demonstration, a qualitative study of the first year of implementation. The report will highlight best practices from the 10 pilot sites and surface opportunities to incorporate two-generation strategies in Federal, state, and local policy.

“By coordinating and integrating efforts we actually get a better result. We’re working together collaboratively and utilizing the resources we have in the best possible way.”-- Department of Agriculture Secretary Thomas J. Vilsack

From distance learning and telemedicine to home visiting and mobile delivery of summer meals, for nearly eight years the Obama Administration has invested in innovative approaches to connect low-income families in rural and tribal areas with essential services. Through Rural IMPACT, we will continue to work hand-in-hand with rural communities to move children and parents on the path towards economic security.

Chad Maisel is a Senior Policy Advisor with the White House Domestic Policy Council