The share of Americans without health insurance has fallen rapidly in recent years, declining to 8.6 percent in the first quarter of 2016, the lowest level on record. Many analyses of these gains have highlighted historic progress for adults, including the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) analysis estimating that 20 million non-elderly adults had coverage thanks to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as of early 2016. But children have also seen important gains in insurance coverage in recent years, thanks in large part to improvements to the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enacted in the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA)—which President Obama signed during his first month in office—and the broader coverage expansions in the ACA. From 2008 through the first quarter of 2016, the uninsured rate among children has fallen by almost half from 9.5 percent to 5.3 percent, resulting in more than 3 million additional children having health insurance. This increase in children’s coverage is improving families’ ability to get kids needed health care. Evidence from earlier coverage expansions suggests that children who gained coverage through CHIPRA and the ACA will also see improved health, education, and labor market outcomes later in life.

Children’s Uninsured Rate Has Fallen by Almost Half Since 2008

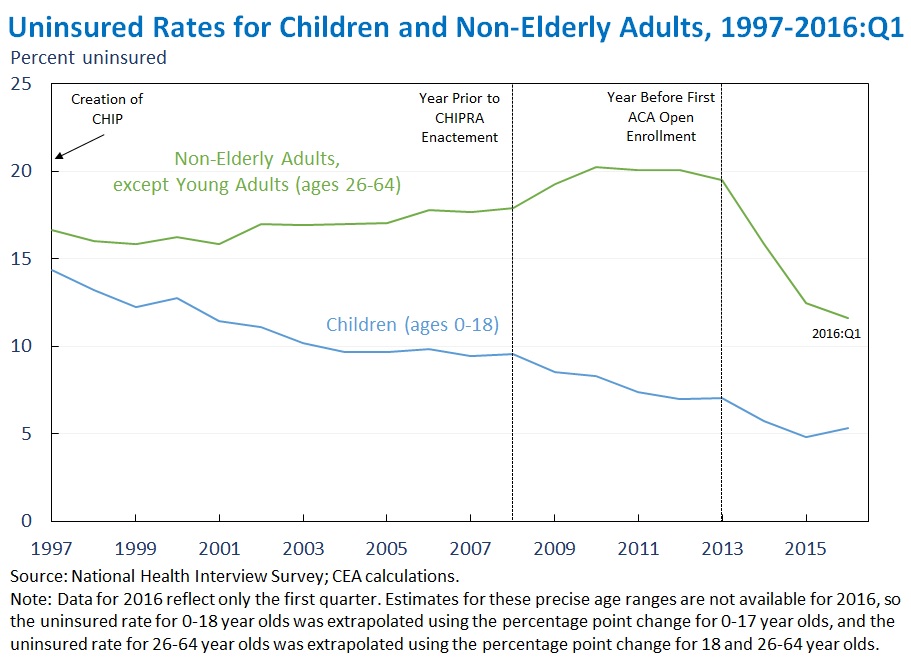

In 2008, the year before President Obama took office, 9.5 percent of children (ages 0-18) lacked health insurance coverage.[1] The uninsured rate among children has declined rapidly since that time, standing at an estimated 5.3 percent in the first quarter of 2016, a 44 percent decline. Had the uninsured rate among children instead held steady at its 2008 level, an additional 3.3 million children would have lacked health insurance coverage in the first quarter of 2016.[2] (Excluding post-2013 gains for 18-year-olds, which are already included in HHS’ estimate that 20 million adults gained coverage because of the ACA, the cumulative gains are 3.1 million.)

Two major policy actions—improvements to CHIP and the broader coverage expansions under the ACA—likely account for much, and perhaps all, of these gains. In President Obama’s first month in office, he signed CHIPRA; similar legislation had been vetoed twice at the end of the prior Administration. CHIPRA sought to build on CHIP’s success in reducing the uninsured rate among children during the late 1990s and early 2000s by extending the program’s funding while giving States additional flexibility and incentives to simplify enrollment, improve outreach, and expand eligibility. (In 2015, Congress voted on a bipartisan basis to extend funding for CHIP, as well as many of the policy improvements introduced in CHIPRA, through 2017. The President’s Fiscal Year 2017 Budget proposes a further extension through 2019.)

In the years following CHIPRA’s enactment, the children’s uninsured rate resumed the rapid decline that had ceased in the mid-2000s. From 2008 through 2013, the uninsured rate among children declined by around one-quarter, equivalent to 1.9 million children gaining coverage. Strikingly, uninsured rates for adults actually rose during this period—likely driven by the Great Recession and its aftermath—suggesting that the uninsured rate among children might actually have risen in the absence of policy changes.[3] Consistent with this time series evidence, research examining specific changes that States made to their Medicaid and CHIP programs in response to CHIPRA has concluded these changes were effective in expanding coverage for children.

Children have also benefited from the comprehensive ACA coverage expansions that took effect at the beginning of 2014, including Medicaid expansion, the creation of the Health Insurance Marketplace, and the introduction of financial assistance for people purchasing Marketplace coverage. For low- and moderate-income children already eligible for Medicaid and CHIP, these provisions streamlined the enrollment process and likely increased awareness of the coverage options that were already available. For higher-income children, the Marketplaces provided new affordable coverage options. The implementation of these provisions has coincided with another substantial decline in the uninsured rate among children, equivalent to an additional 1.4 million children gaining coverage. (Focusing only on children under age 18 to avoid any overlap with HHS’ estimate that 20 million adults have gained coverage because of the ACA, the gains from 2013 to the first quarter of 2016 corresponds to 1.2 million children.)

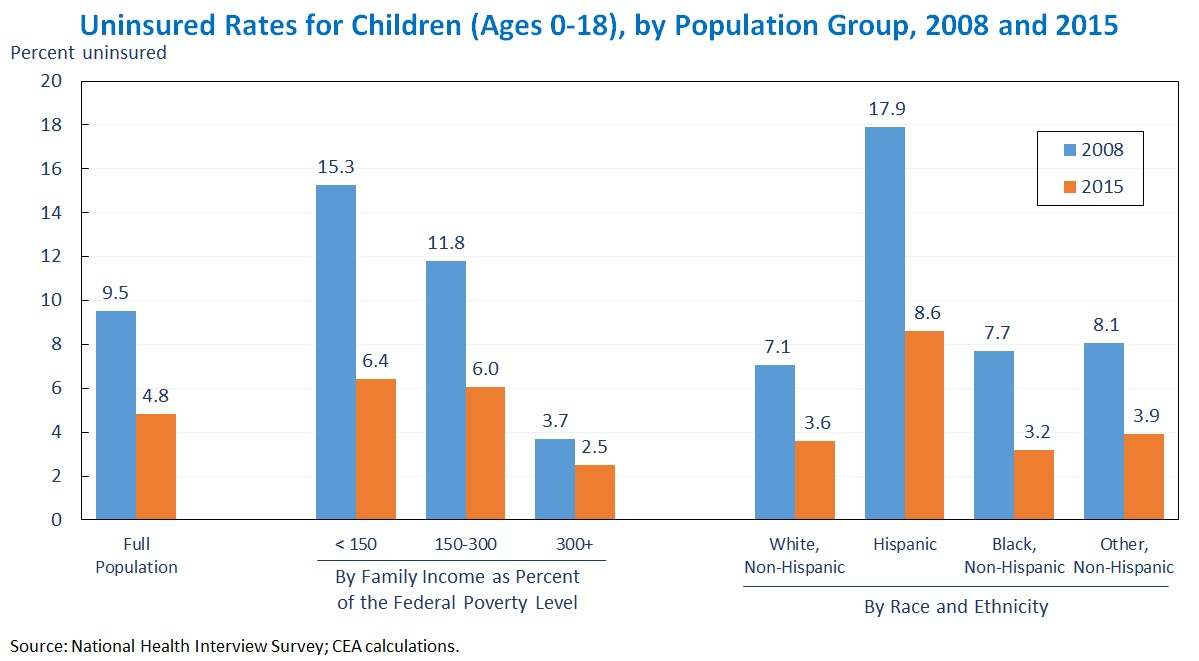

Groups with Highest Uninsured Rates in 2008 Saw the Largest Gains

The gains in children’s insurance coverage since 2008 have been broad-based, with improvements across all income groups and all racial and ethnic groups.[4] Groups that had the highest uninsured rates in 2008 have generally seen the largest gains, with the result that differences in the risk of being uninsured across income groups and racial and ethnic groups have narrowed sharply. For example, in 2008, children in families with incomes less than 150 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) were 11.6 percentage points more likely than children in families with incomes at or above 300 percent of the FPL to lack health insurance; by 2015, that gap had shrunken by almost two-thirds to just 3.9 percentage points.

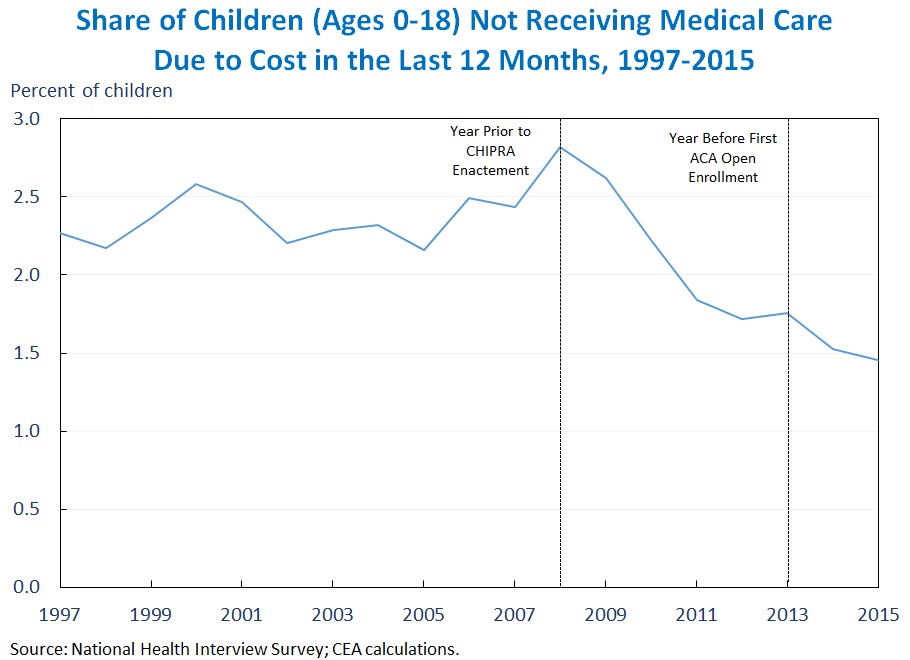

Gains in Insurance Coverage Have Coincided With Improvements in Access to Care

In parallel with this increase in insurance coverage, children have experienced substantial improvements in access to care. The share of children who failed to receive medical care due to cost during the last 12 months declined by almost half from 2008 to 2015, from 2.8 percent in 2008 to 1.4 percent in 2015. In light of the timing of the decline and evidence from a variety of settings that insurance coverage substantially improves access to care, it seems likely that this improvement in access to care among children is, at least in significant part, a result of the increase in children’s insurance coverage in recent years.

Children’s Coverage Generates Long-Term Benefits for Health and the Economy

A growing body of economic research examining past coverage expansions finds that having insurance coverage generates substantial benefits later in life for health and labor market outcomes. One recent set of studies took advantage of a feature of Federal Medicaid eligibility rules that caused children born in October 1983 or later to be more likely to qualify for Medicaid coverage during their pre-teen and early-teen years than children born before October 1983. This work found that, in the socioeconomic groups most affected by the change in eligibility rules, qualifying for Medicaid resulted in better health, including lower mortality in their late teen years, as well as lower hospitalization rates in adulthood. The authors calculate that future savings from reductions in hospitalization as a result of having Medicaid coverage will offset a meaningful fraction of the cost of the additional years of coverage.

A related literature using variation in Medicaid and CHIP eligibility criteria across states and over time has concluded that having insurance coverage in childhood also has important benefits for long-run labor-market outcomes. Having Medicaid or CHIP coverage in childhood substantially increases the likelihood of completing high school and college. A related study concluded that female children who had Medicaid or CHIP coverage in childhood had higher earnings in adulthood. That study also finds that both male and female children paid more in income and payroll taxes in adulthood, which the authors conclude may defray a substantial fraction of the upfront fiscal cost of providing coverage.

[1] Except where otherwise noted, this blog post defines a child as a person age 0-18 years in order to align with the definition used when determining eligibility for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

[2] Estimates for 0-18 year olds have not yet been reported for the first quarter of 2016, but estimates for 0-17 year olds are available, so the uninsured rate for 0-18 year olds was extrapolated to the first quarter of 2016 using the percentage point change in the uninsured rate for 0-17 year olds.

[3] This comparison focuses on adults age 26 and older because young adults ages 19-25 were being affected by the Affordable Care Act’s provision allowing young adults to remain on a parent’s plan until age 26, which took effect in September 2010.

[4]This section and the remainder of the blog post use data through 2015 only because individual-level data for the first quarter of 2016 are not yet available.

Matt Fiedler is Chief Economist at the Council of Economic Advisers.