Economic growth in the third quarter reflected the combination of solid domestic demand and volatile transitory factors. Personal consumption continued to grow at a solid pace, while inventory investment slowed sharply and net exports were largely neutral for overall growth. Over the past year, slowing global demand has been a headwind for the U.S. economy, and unnecessary austerity and fiscal brinkmanship have posed unnecessary risks for consumer spending and business investment. That’s why this week’s budget agreement is a particularly important step—adding an estimated 340,000 jobs in 2016, reducing uncertainty, and enabling productivity-enhancing investments. But there is more work to do to foster long-term growth, including increasing investments in infrastructure, reauthorizing the Export-Import Bank, and opening new markets for our exporters through high-standards free-trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership. We look forward to continuing to work with Congress to make progress on these important priorities.

FIVE KEY POINTS IN TODAY'S REPORT FROM THE BUREAU OF ECONOMIC ANALYSIS (BEA)

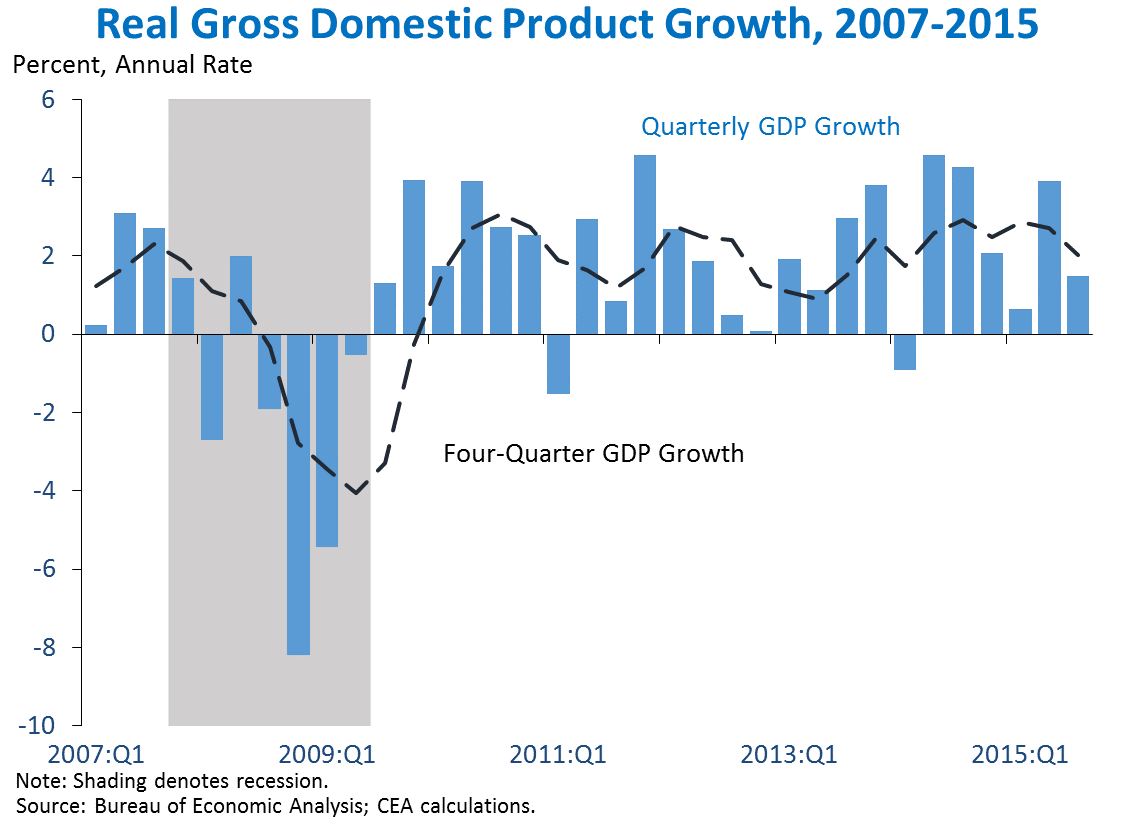

1. Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rose 1.5 percent at an annual rate in the third quarter, according to the BEA’s advance estimate. In the third quarter, GDP grew at a slower pace than in the second, with much of the difference attributable to a large decline in inventory investment—one of the most volatile components of economic output—which subtracted 1.4 percentage points from overall growth. Personal consumption spending continued to grow at a robust pace, rising 3.2 percent at an annual rate in the third quarter. Reduced oil drilling continued to weigh on business investment, subtracting from overall growth. Exports grew in the third quarter but at a subdued pace, likely reflecting weaker foreign demand. Export growth remains considerably slower than the pace observed earlier in the recovery. Overall, GDP rose 2.0 percent over the past four quarters.

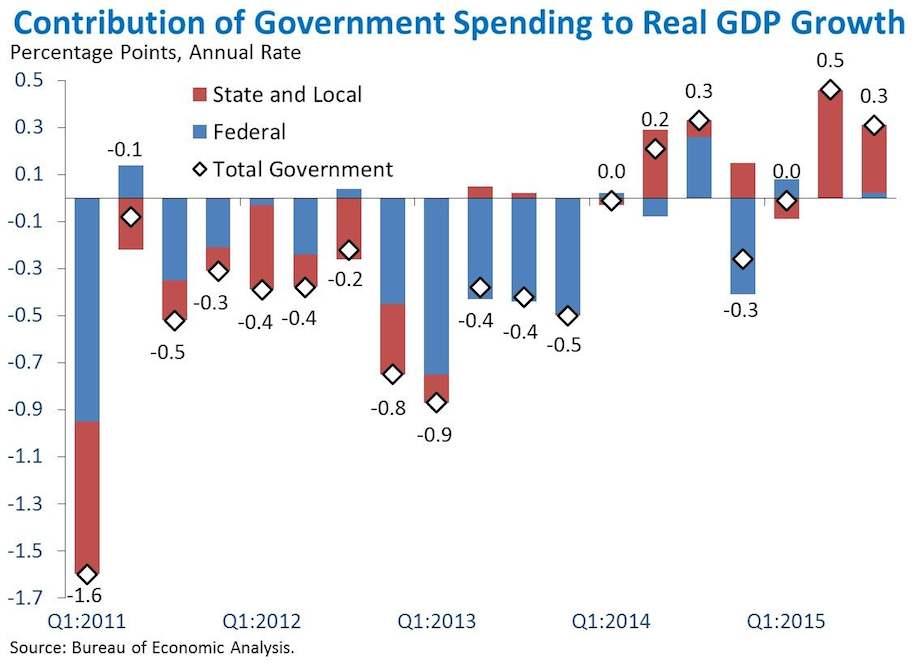

2. The “fiscal drag” that subtracted from GDP growth from 2011 to 2013 has eased in recent years, a positive development that will be further supported by this week’s federal budget deal. From 2011 through 2013, declining government spending subtracted an average of 0.5 percentage point per year from GDP growth. Most of that drag is attributable to lower federal spending. At the same time, increased uncertainty as a result of fiscal brinkmanship may have further hurt consumer spending and business investment. Since the Murray-Ryan budget agreement in 2013 relieved a portion of the sequester over 2014 and 2015, this fiscal drag has diminished. Government spending has been a positive contributor on average since then, and fiscal brinkmanship has been reduced. The two-year budget agreement announced this week totals 0.2 percent of GDP or nearly 90 percent of the discretionary sequester relief proposed by the President for FY 2016, and it will help continue avoid unnecessary fiscal drag in the years to come while also increasing certainty for businesses and consumers.

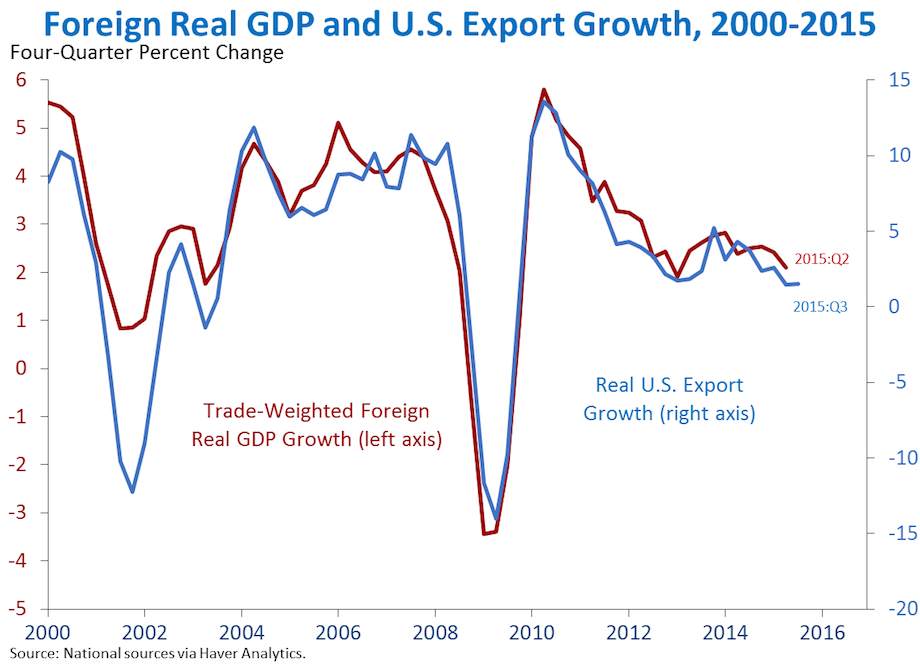

3. Net exports have subtracted 0.7 percentage point from GDP growth over the past four quarters, reflecting the continued headwinds from slowing foreign growth on U.S. exports. The volume of U.S. exports to foreign countries is heavily sensitive to foreign GDP growth. Indeed, year-over-year foreign GDP growth—when weighting countries by the volume of their annual trade with the United States—explains much of the variance in U.S. export growth. To the extent that the global slowdown persists, it will likely continue to weigh on U.S. export growth, as it has over the past year. In the third quarter, export growth continued to slow and remains lower than the pace observed earlier in the recovery; net exports did not contribute to overall growth in this quarter. The sensitivity of our exports to foreign demand—especially in an environment where foreign demand is slowing—underscores the importance of reducing trade barriers and opening foreign markets to our exports.

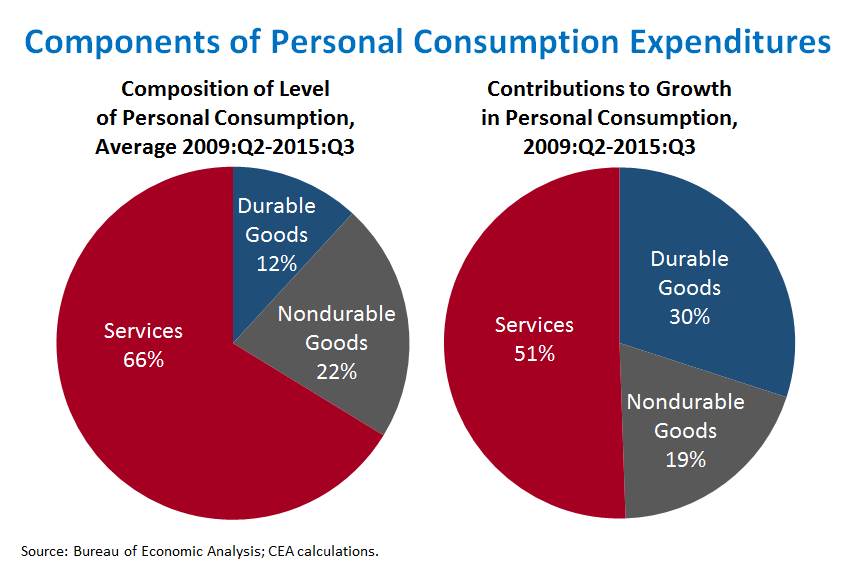

4. The recent strength in personal consumption growth reflects a disproportionate contribution from spending on durable goods. Goods consumption accounts for only about one third of total consumer spending. But goods have contributed disproportionately to spending growth in this recovery, contributing half of consumption growth since mid-2009. As in many recoveries, durable goods consumption has been particularly strong—accounting for only 12 percent of total consumption but 30 percent of consumption growth throughout this recovery. The disproportionate strength of durable goods consumption was apparent in this third quarter, as durable goods consumption accounted for more than 20 percent of consumption growth. The strength in durable goods consumption reflects an especially fast pace of purchases of big-ticket items like automobiles, and is consistent with the current high levels of consumer confidence and improved consumer balance sheets.

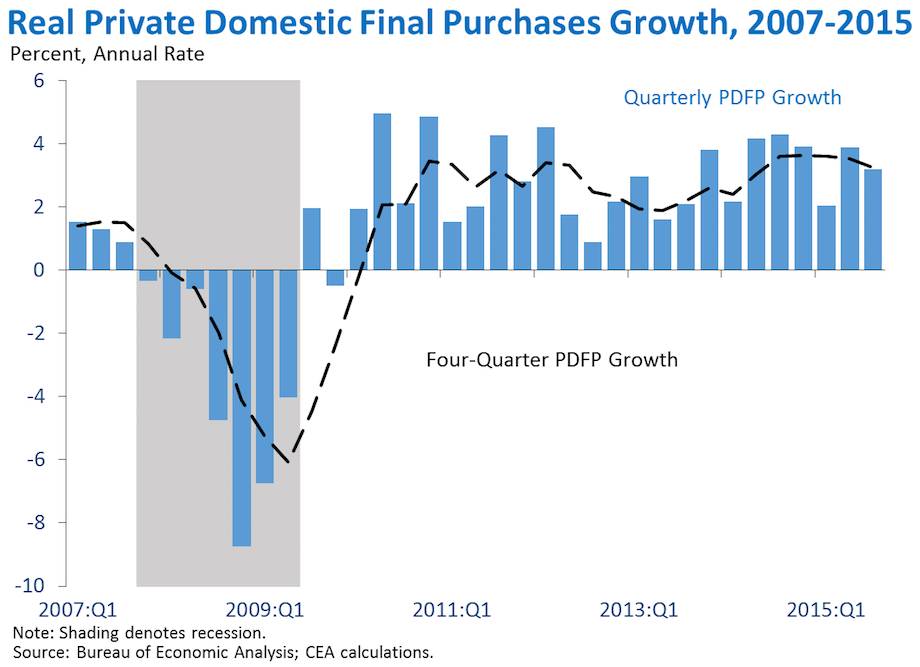

5. Real private domestic final purchases (PDFP)—the sum of consumption and fixed investment—rose 3.2 percent at an annual rate in the third quarter and is growing at a faster year-over-year pace than overall GDP. Real PDFP—which excludes noisier components like net exports, inventories, and government spending—is generally a more reliable indicator of next-quarter GDP growth than current GDP. PDFP aims to measure signals of future economic growth by eliminating some of the noisy components in GDP. However, to the extent that systematic patterns emerge in global growth, for example, the information contained in net exports may contain an important signal about the headwinds we face from abroad (see point 3). The especially large gap between PDFP growth and GDP growth over the past four quarters is attributable to both net exports and inventory investment, an especially volatile category of spending.

As the Administration stresses every quarter, GDP figures can be volatile and are subject to substantial revision. Therefore, it is important not to read too much into any single report, and it is informative to consider each report in the context of other data that are becoming available.