Ed. note: This is cross-posted on the National Endowment for the Arts' blog. See the original post here.

As Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), I work with a dedicated and passionate group of people and organizations to support and fund the arts in communities across America. I believe what we do is so important, not just to celebrate and affirm the arts as a national priority critical to America's well-being and future; the power of the arts can be transformative and I've experienced firsthand how this works. My story is especially relevant today as the White House Task Force on New Americans has released its report to the President on recommended actions the federal government can take to build integrated and welcoming communities across the nation.

I was born into multiple cultures, often with seemingly opposing perspectives. Had I not been engaged with the arts, I don’t know if I would have been able to make sense of my own life.

My mom and dad were from China. My dad came to America in 1948 to get his Ph.D. When the Communists entered China, and he was attending school in the U.S., he knew he would not be able to return to his home country, so he had to remake his life from what he knew before.

My mother was a teenager when the Communists entered her hometown of Qingdao in 1949. Her parents made a bold decision to sneak her out of China, so she could have freedom to be herself. She had just graduated from high school, and she was at the age where she could do anything she wanted with her life. They snuck her on a train by herself with no ticket; a train that would take eight days to get to Hong Kong. She couldn't carry suitcases, because she would look conspicuous. So, she wore eight pairs of underwear; one over the other, and put her money in her underwear. They said goodbye to each other, not knowing if they would ever see each other again, which they never did. She escaped 141 interrogations over the eight-day train ride.

I, on the other hand, was born in Oklahoma. I grew up in Arkansas, 11,000 miles from China, and equally as far away from the traditional Chinese way of life. I juggled living in two opposite cultures simultaneously. My parents wanted me to assimilate, so that I would fit in at school. They spoke Mandarin to each other at home, but wanted me to only speak English. They liked to eat bok choy and noodles. I liked to eat pizza and corn dogs. My parents were not opposed to the arts, but they didn’t place a lot of emphasis on them, either, other than making me take piano lessons.

When I was nine, my father died of cancer. Many nine-year-olds lack the vocabulary to articulate their grief over the loss of a parent. This was doubly compounded for me, since Mandarin had been my parents’ native language, but not mine.

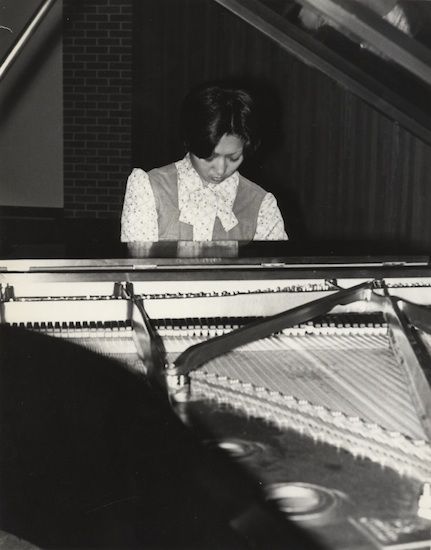

But when I played the piano, I found an avenue to express myself. Music had the ability to soothe me. I felt as though I belonged, because I had an avenue of expression beyond just the linear use of everyday words. Over time, I became interested in music and art activities, and ultimately I majored in music in college.

Years later, the lessons of how to navigate through and embrace multiple perspectives came into play when I joined the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts. We were charged with ensuring that the many voices involved in the project eventually spoke in concert. There were the artistic concerns of musicians and performers. There was our board who addressed specifics within the budget. And there was a community relying on the center to honor the performing arts and strengthen their city. All views that needed to be heard.

But because of my childhood, I was comfortable with juggling different perspectives. One day, I’d be talking with dry-wallers, and the next day, I’d be talking with oboe players.

Creative leaders need to be able to stand in the middle of ambiguity and different perspectives. But they also have a responsibility to bring people together and communicate the vision, especially when the vision involves bringing together new perspectives around a common theme.

The same responsibility is now present in my work as the chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts. Where I once talked with dry-wallers and oboe players, I’m now talking with elected officials, business leaders, artists, and arts organizations. And what about the taxpayers? We want to be good stewards of your money. And what about the children? We want to spark creative thinkers at an early age. So, my ability to understand and manage different viewpoints is now critical, especially as we begin to work on focusing these different perspectives around a single vision: that the arts are an essential component of our everyday lives.

Art is found on museum walls. It is seen on stage. But it is not removed from the rest of society, or isolated in some ivory tower. The arts are all around us, touching every aspect of our world, whether we’re aware of it or not. They contribute to our economy. They revitalize neighborhoods. They increase our sense of well-being. They are an equalizer in communicating with families within our communities who do not use English as their first language. They spark new ideas in science and technology, and they draw out our feelings to help us understand ourselves. They provide us with an avenue of expression, just like they did for me as a child.

As the White House Task Force on New Americans begins its work of implementing its recommendations, the NEA will seek opportunities to contribute to its efforts by building bridges among immigrants and refugees and their larger communities, including the arts. We hope others in local communities--including community groups, business leaders, state and local governments, long-time residents, and immigrants and refugees themselves--will also answer this call. To learn more about the Task Force and how you can contribute, visit obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/NewAmericans.

Jane Chu is Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA).