Over the past century, American women have made tremendous strides in increasing their labor market experience and their skills. On Equal Pay Day, however, we focus on a stubborn and troubling fact: Despite women’s gains, a large gender pay gap still exists. In 2013, the median woman working full-time all year earned 78 percent of what the median man working full-time all year earned. A new issue brief from the Council of Economic Advisers examines what we know about the pay gap.

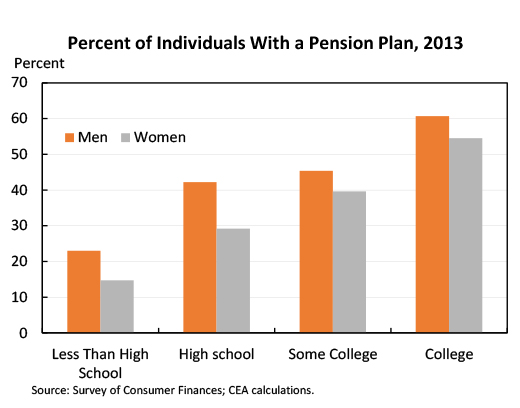

1. The pay gap goes beyond wages and is even greater when we look at workers’ full compensation packages. Women are less likely to have an offer of health insurance from their employer, have retirement savings plans, or have access to paid leave, and perhaps as a result, they are more likely to take leave without pay.

These broader measures of compensation show that the pay gap is not just about differences in earnings or wages. But why do women earn less than men? Let’s break it apart so we can better understand what is driving the pay gap.

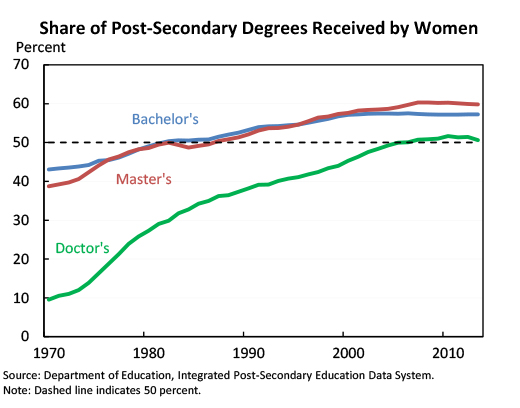

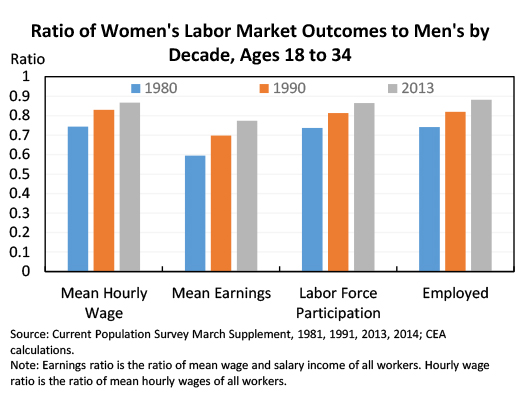

2. In the past, men had greater levels of both education and experience than women, but these gaps have closed since the 1970s. While men were more likely to graduate from college in the 1960s and 1970s, since the 1990s, the majority of all undergraduate and graduate degrees have gone to women. While on-the-job experience is also an important determinant of wages, and in the past, women typically left the labor force after marrying or having children, women today are more likely to work throughout their lifetimes. For example, economists found that one-third of the decline in the pay gap over the 1980s was due to women’s relative gains in experience. Today, more of the pay gap is unexplained, leaving a greater role for factors beyond differences in education and experience.

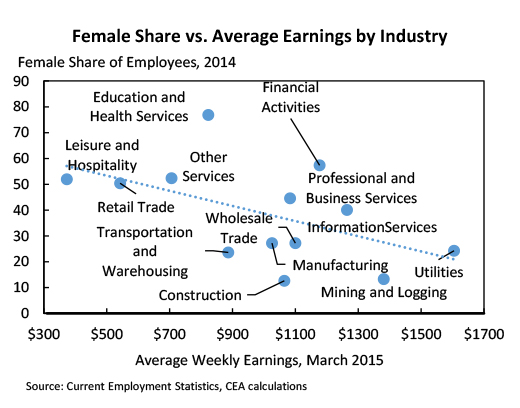

3. Although occupational segregation has fallen, women are still more likely to work in lower-paying occupations and industries. Even when women and men are working side-by-side performing similar tasks, however, the pay gap does not fully disappear. Economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn found that differences in occupation and industry explain about 49 percent of the wage gap, but 41 percent of the wage gap is not explained by differences in educational attainment, experience, demographic characteristics, job type, or union status.

The real question, however, is why men and women end up in different occupations in the first place and what we can do to make it easier for women to succeed in high paying occupations. For instance, from college, women are under-represented in STEM fields, receiving only 35 percent in STEM bachelor degrees. However, even among women who begin a science-related career, more than half leave by mid-career, double the rate of men. Forty percent of those who leave cite a “macho” culture as the primary reason.

4. Motherhood is associated with a wage penalty and lower future career earnings. One reason the gender wage gap has narrowed faster among younger women is that between 1980 and 2013, the median age of first birth rose from 22.6 to 26.0. Because motherhood is associated with a wage penalty and lower wage gains later in a woman’s career these delays in childbirth have helped narrow the pay gap. Research has shown that delaying child birth for one year can increase a woman’s total career earnings and experience by 9 percent. But research shows that a lack of paid leave is one reason mothers with infants leave the labor force and therefore earn less later in life. So policies providing paid sick and family leave encourage women to participate in the labor force and therefore bolster their lifelong earnings.

5. In general, the pay gap grows over workers’ careers. Young people tend to start their careers with more similar levels of earnings and over time the gender gap grows. While some of the growth in the pay gap is because women are more likely to take time out of the labor force and work fewer hours, a pay gap remains even after accounting for time out of the workforce and job tenure. Women get fewer raises and promotions, partially because they negotiate less. But even when women do negotiate, they are likely to receive less than men or be penalized for violating social norms.

While the gap in negotiated salaries are small in situations where bargaining expectations are clear, when expectations and norms are not clear, women receive less than men. On this dimension, increasing pay transparency can help ensure non-discrimination, since even though employers are prohibited from discriminating, in cultures of pay secrecy, it is more difficult to enforce non-discrimination requirements. In addition, other work has also found that women are more likely to be penalized for initiating negotiations. This type of implicit bias leads to gaps that grow over a woman’s lifetime.