This morning, economist Edward Glaeser wrote a blog post over at the NYT charging that Recovery Act spending isn’t going where it’s needed most. Based on a subset of Recovery Act spending, he claims that per capita spending in a state is actually negatively correlated with the state’s unemployment rate – in other words, the higher the unemployment rate in the state, the less money it gets per person.

He’s wrong about that. Not only does he leave out a major chunk of Recovery Act spending, but the chunk he leaves out includes the programs that are targeted most directly at unemployment. When you put those data back in, as we do below, you get a correct sense of the extent to which the Act is effectively targeting people and places that need help.

Glaeser’s blog post is based on data reported by direct recipients of Recovery Act, which only covers certain programs—those in which the Recovery Act makes a grant or gives a contract or loan to an entity that will perform a project, like fixing a bridge.

But the chunk he leaves out includes payments that go straight to individuals in need. Since his targeting measure is unemployment, the most important omission here is the increased Unemployment Insurance payments that the Recovery Act provided – tens of billions of dollars of aid that have provided a crucial lifeline to more than 20 million unemployed workers during this downturn.

He also leaves out major aid to states through the Medicaid system, which has helped prevent layoffs of teachers and other public servants across the country – and which, by the way, was distributed based on a formula that explicitly considers a state’s unemployment rate (such data are publicly available here).

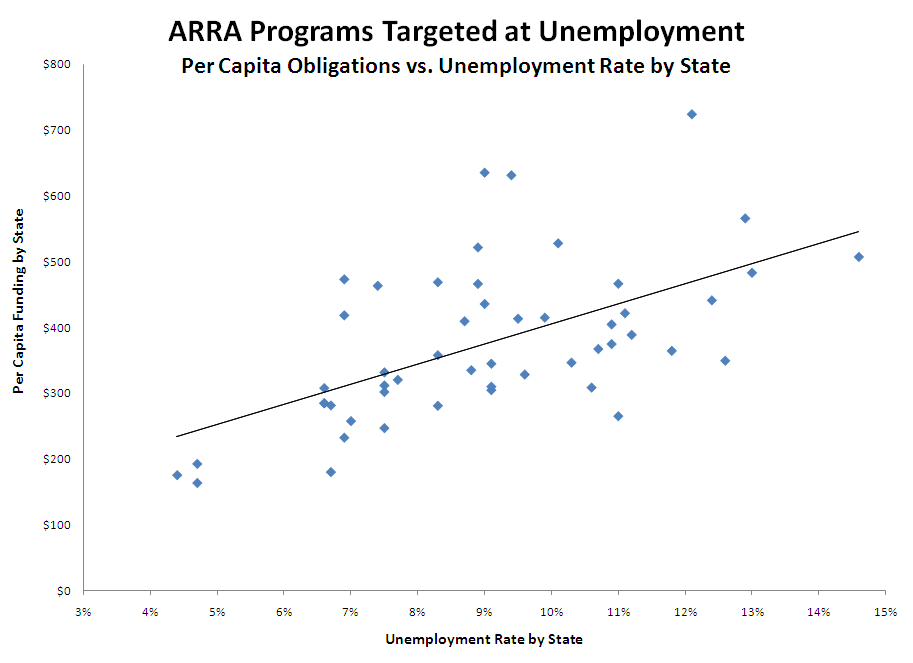

Lo and behold, when you actually look at the entire Recovery Act, the negative correlation Professor Glaeser complains about disappears. This is, of course, no surprise – if you leave out the Recovery Act programs that are targeted at economic hardship, the Recovery Act will look to be poorly targeted. And by the way, these programs account for over $120 billion in funds put to work so far, so we’re not talking small change here.

Here is the very different picture you get when you look at these targeted programs – expanded unemployment insurance, aid to states through the Medicaid system, food stamps, emergency grants to the Temporary Assistance for Needy family system, job training, and youth summer employment:

And then there’s another side of this story. As the figure shows, the programs that are targeted at unemployment are doing their job. But not every program in the Recovery Act is intended to send money the states with the highest unemployment rates.

In fact, that’s why the package is called the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act – it’s designed not just to get aid to those who need it most, but to make investments that will help lay the foundation for robust, sustainable growth in the future.

The Recovery Act cannot meet the vision of the President and Vice President if we were to limit it solely to projects in states with higher than average unemployment. Throughout the country, it must make key investments in infrastructure, including not just roads and bridges but transit, high-speed rail, broadband, clean energy, and the smart grid. And even when it comes to good, old-fashioned roads and bridges, those investments have to be made where they’re needed, not just wherever unemployment is the highest.

Glaeser raises perfectly valid and important points about making sure our investment decisions are smart ones, not driven by politics or outdated formulas. And that’s what we’re trying to do here. When it comes to both recovery and reinvestment, the Act is hitting the target.

Jared Bernstein is Chief Economic Advisor to the Vice President, and Executive Director of the Middle Class Task Force