Today, we are releasing the Economic Report of the President for 2010. For more than sixty years, the Economic Report has provided a nearly contemporaneous record of how Administrations have interpreted economic developments, the motivation for policy actions, and the results of those interventions. This year’s volume has attempted to stay true to this proud legacy. It provides a detailed economic history of the first year of the Obama Administration. It examines the economic challenges that we face as a Nation, the many policy actions that have already been taken to address these challenges, and the President’s proposals for further action.

The economic challenges facing the Nation when President Obama took office were among the greatest in our history. Last January, the American economy was truly in freefall. Real GDP was falling at an annual rate of more than 6 percent and the U.S. economy was losing jobs at the devastating rate of almost 800,000 per month. Our financial markets, having narrowly avoided collapse in the financial panic of the early fall of 2008, were paralyzed with fear, and borrowers of all sorts, from households to small businesses to large corporations, were having trouble accessing the credit necessary for normal economic activity. As a scholar of the 1930s, I can say that the threat of a second Great Depression was both genuine and terrifying.

But as great as the immediate challenges were, our country’s economic problems were also deeper and more long-standing. For nearly a decade, typical American families had seen their incomes stagnate, instead of rising steadily as they had for generations. Much of the economic growth that the United States experienced in the past decade was fueled by consumers and the government running up large debts, aided by a financial system better at making short-term profits than managing long-term risks. Rapidly rising health care costs were squeezing both family incomes and the government’s budget. And as a country, we were failing to invest as we needed to in education, new energy technologies, and basic research and development.

Over the past year, the President, working with Congress, has sought to rescue the economy from the immediate crisis, rebalance the economy toward greater investment and exports and away from unsustainable budget deficits, and begin the process of rebuilding the economy on a stronger foundation of quality, affordable health care, better education and job training, clean energy, and innovation. The Economic Report of the President details both the actions we have taken so far and the President’s plans for continued progress.

While it is impossible to describe the whole volume in detail, let me highlight the findings from three chapters and discuss how the other chapters fit into the Report.

Rescuing an Economy in Freefall

The Employment Act of 1946, which created both the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) and the Joint Economic Committee, made explicit that it was the role of the Federal Government “to promote maximum employment, production, and purchasing power.” Chapter 2 of the Economic Report discusses the unprecedented actions that have been taken to end the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009. It is no surprise that this chapter is the longest in the book; the actions that have been taken are many. They include not only the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, but a number of smaller fiscal actions such as the “cash for clunkers” program to stimulate the automobile industry and important extensions of key tax cuts and unemployment benefits. They include a range of financial sector interventions, such as the stress test of the nineteen largest financial institutions, new lending programs, and support for the government sponsored enterprises. Rescue actions also include programs to stabilize the housing market and help responsible homeowners avoid foreclosure, as well as conventional and extraordinary monetary policy measures conducted by the Federal Reserve.

Chapter 2 also discusses the evidence that these actions have had a tremendous impact. Our financial markets are secure again and credit spreads, a common measure of financial market unease, are down almost to historical norms. Despite overwhelming downward momentum, the trajectory of the economy has changed radically. By the third quarter of 2009, real GDP was growing again, and last Friday we learned that the unemployment rate fell three-tenths of a percentage point in January. Experts across the ideological spectrum credit the unprecedented policy actions with preventing an economic cataclysm and putting us on the road to recovery.

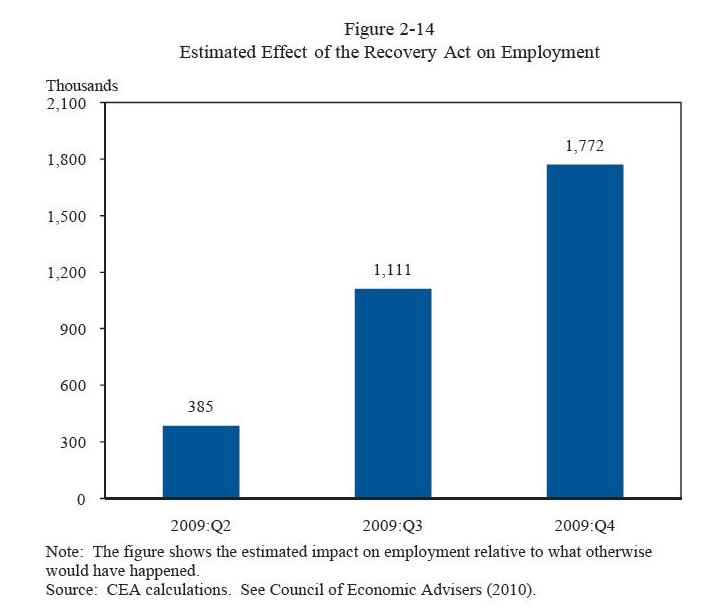

Here I want to discuss particularly the impact of the Recovery Act. This Act is the great unsung hero of the past year. It has provided a tax cut to 95 percent of America’s working families and thousands of small businesses. It has meant the difference between hanging on and destitution for millions of unemployed workers who had exhausted their conventional unemployment insurance benefits. It has kept hundreds of thousands of teachers, police, and firefighters employed by helping to fill the yawning hole in state and local budgets. And, it has made crucial long-run investments in our country’s infrastructure and jump-started the transition to the clean energy economy. All told, the Recovery Act has saved or created some 1½ to 2 million jobs so far, and is on track to have raised employment relative to what it otherwise would have been by 3.5 million by the end of this year. When the political rancor of the moment passes and dispassionate analysis is done by experts, I have no doubt that the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 will be viewed as one of the great triumphs of timely, effective, countercyclical macroeconomic policy—just exactly the type of policy the Employment Act of 1946 was designed to facilitate.

While conditions are far better than they would have been without the actions that were taken, it is clear that substantial challenges remain. The unemployment rate is 9.7 percent and the revised data show that employment has fallen 8.4 million from its peak in December 2007. For this reason, the President has called for important targeted actions to spur job creation. One of these is the Small Business Jobs and Wages Tax Cut. The Council’s analysis suggests that such a tax cut for hiring could be a particularly cost-effective way to generate substantial increases in employment at this point in the recovery. The Administration also supports continuation of essential relief measures to aid the unemployed and to keep teachers, police, and first responders employed by strapped state and local governments.

In another chapter on rescue measures, the Economic Report discusses the worldwide response to the crisis. It shows that a coordinated move to monetary and fiscal expansion allowed countries around the globe to climb out of the crisis simultaneously. In this way, worldwide growth helped to support the growth in each individual country.

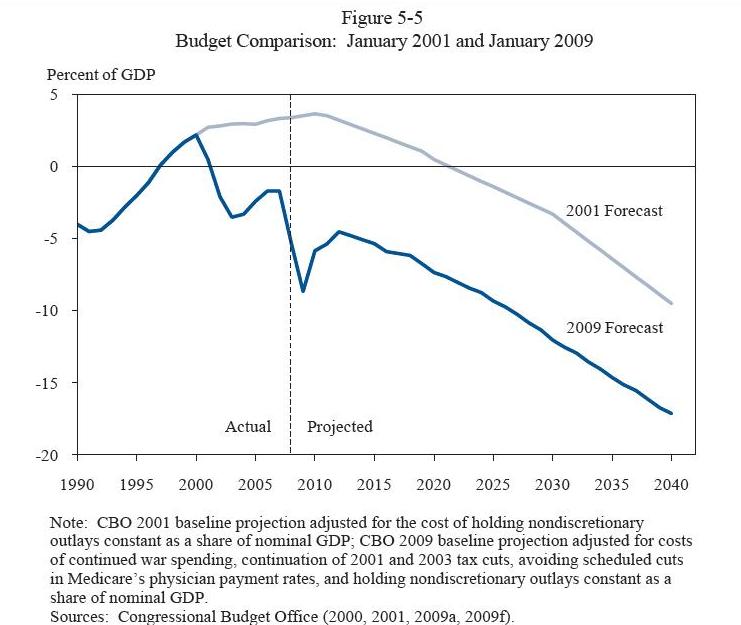

Rebalancing the Economy on the Path to Full Employment

In his State of the Union address, the President highlighted the problem of the Federal budget deficit. As described in Chapter 5 of the Economic Report, the Federal budget situation had deteriorated substantially before the recession. Largely because of two tax cuts, two wars, and a major new Medicare drug benefit that were not paid for, the budget surpluses of the 1990s had been replaced by substantial actual and projected future deficits long before the recession began at the end of 2007. The recession obviously made the deficit larger, as did the actions to address the recession, such as the Recovery Act. But by the end of the decade, the rescue actions raise the deficit by just one-quarter of one percent of GDP. The much more significant factors in accounting for the long-run deficit are the unpaid-for policies of the past decade and Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security costs. Whatever their cause, the medium- and long-run deficits that are projected are unsustainable, and will gradually crowd out investment and impede growth if they are not addressed.

Chapter 5 explains the logic of the Administration’s proposed fiscal target. By balancing the primary deficit (that is, the deficit net of interest costs) in the medium run, we will stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio. To achieve this, the Administration has proposed a sensible plan that includes a three-year freeze of nonsecurity discretionary spending and a bipartisan commission to build consensus on other needed actions. At the same time, our budget contains $100 billion for further targeted jobs measures and additional funds for continuing relief efforts. Such a blending of near-term emergency spending and a medium- and long-term plan for fiscal sustainability is the sensible policy for this point in the recovery.

Other chapters of the Economic Report build on the theme of restoring balance to the American economy. CEA analysis suggests that American families are likely to be saving more in the future than they did in the past decade. To fill the gap left in demand, business investment and net exports will need to rise. The Administration has proposed a number of policies to encourage this healthy transition. Likewise, our financial regulatory system needs to be revamped to match 21st century financial innovation. We need to put in place sensible rules of the road to ensure that we do not return to the bubble and bust economy that has wreaked such havoc on the American economy in the past decade.

Rebuilding a Stronger Economy

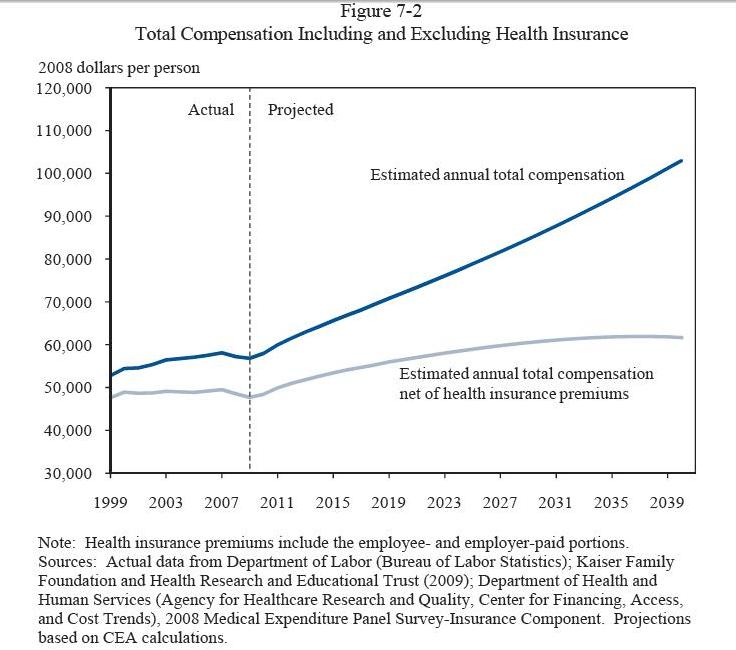

In no area are the long-run challenges facing the American economy greater than in health care. We are all too aware of the statistics on the millions of Americans without health insurance. But, as we discuss in Chapter 7 of the Economic Report, the troubles are broader than that. American families with insurance face further stagnation and eventual decline in take-home wages as rising health insurance costs consume a larger and larger fraction of total compensation. Federal, State, and local governments face unsustainable pressure on their budgets as government health expenditures rise along with overall health care costs. That is why the President has made health insurance reform a top priority.

Working with Congress, we have already achieved a great deal. The extension of the Children’s Health Insurance Program will bring coverage to as many as 4 million more children. The Recovery Act provided support for unemployed workers to help them maintain health insurance benefits and made pioneering investments in health information technology, health centers, and research into which treatments are likely to work best. Both houses of Congress have passed reform legislation that would do so much more to slow the growth rate of health care costs, and make insurance coverage more secure for those who have it and affordable for the millions of Americans who do not. Successful completion of reform legislation is essential to our long-run economic prosperity, taming our government budget deficit, and making American families more secure in their health insurance coverage.

Three other chapters of the Economic Report discuss additional areas where the President believes we need to rebuild our economy stronger than before. Education is a key ingredient to improved productivity and wages. Clean energy holds the promise of generating good jobs at the same time that we reduce harmful greenhouse gas emissions. And innovation is the ultimate engine of economic growth. In each of these areas, the President and Congress have already made key substantive investments. But, as these chapters describe, there is much more that can and should be done to ensure a brighter future for our children and our country.

As I have described, this year’s Economic Report of the President is a blend of history, analysis, and prescription. It describes what we have been through during the past very difficult year. It describes the many actions we have taken to address both the near-term crisis and our longer-run problems. And, it contains an important agenda of policy actions that will help to ensure that the American economy not only recovers completely, but comes back even stronger than before.

Before I close, I want to acknowledge the outstanding staff of the Council of Economic Advisers who contributed to this report. The CEA is unique among government agencies in that most of the staff turns over every year. Our senior economists are typically professors on leave from universities, and our junior staff are typically students on leave from Ph.D. studies in economics or undergraduate economics majors. This past year, the Council has been blessed with staff of a caliber not seen since the glory days of the CEA in the 1960s, when future Nobel laureates Robert Solow and Kenneth Arrow were senior economists and James Tobin was a member. Leading experts in every field of economics joined the CEA staff this year to try to bring the best professional expertise to the tremendous economic challenges facing the country. The junior staff is equally gifted and has worked eighty hours a week with a cheerfulness and enthusiasm that is truly inspiring. I am indebted to all them, and to the dedicated permanent staff, and this volume reflects their collective wisdom and months of very hard work.

Christina Romer is Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers