The State of the American Child: The Impact of Federal Policies on Children

THE STATE OF THE AMERICAN CHILD:

THE IMPACT OF FEDERAL POLICIES ON CHILDREN

Cecilia Elena Rouse

Member, Council of Economic Advisers

July 29, 2010

Testimony before the Subcommittee on Children and Families

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

United States Senate

Good morning Chairman Dodd, Ranking Member Alexander, and distinguished members of the Subcommittee.

I am very pleased to represent the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) at this important hearing and thank you for your strong commitment to improving the lives of children and their families. I focus my remarks on documenting the status of children in America in three areas: economic status, health, and education. To the extent possible, I have assembled data that reflect their status since the beginning of this recession although at this point such data are often unavailable. I conclude by suggesting four areas in which it is particularly important to bring change in order to improve the well-being of children.

The bottom line is that a good economy is good for the well-being of all, and especially children. Along many dimensions, the biggest gains over the past 20 years occurred during the economic expansion of the 1990s, as poverty rates in families with children dropped dramatically as did some important measures of health, such as rates of infant mortality. Given the link between the economy and child well-being, we must remain vigilant to maintain these gains in the wake of the recent recession, as investments in children are investments in the future prosperity of America.

The State of Children in America

Trends in Economic Status

Between 1990 and 2007, U.S. real gross domestic product grew at an average annual rate of 3.0 percent, and unemployment averaged 5.4 percent; growth was particularly strong during the 1990s. Not surprisingly, the resources available to children improved during this time as family incomes also rose. As evidence, the median income of families with children increased by 12 percent during this period fueled by an increase of 16 percent between 1990 and 2000. Consistent with this economic growth, the percentage of children living below the poverty level decreased from 21 percent to 18 percent between 1990 and 2007, as shown in Table 1. 1

Unfortunately, the recent recession has had a negative impact on this progress. In 2008, the median income for families with children decreased by 2.3 percent from the previous year and the percentage of children living in poverty increased to 19 percent. Moreover, 8.5 percent of children (over 6 million) lived in extreme poverty (defined as having family income less than 50 percent of the poverty threshold). The percentage of children in food-insecure households jumped to 22.5 percent in 2008, up from 16.9 percent in 2007, and is the highest percentage since data collection began in 1995.2 According to the 2010 KIDS COUNT Data Book recently released by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, most experts expect the child poverty rate to increase significantly over the next several years.3

Trends in Child Health

Before the recession the U.S. had also witnessed improvements in child health along many dimensions. For example, the rate of infant mortality – which serves as an important indicator of the health of a nation as it reflects a number of other measures, including maternal health, quality of healthcare, and socioeconomic conditions – decreased from 9.2 infant deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 6.7 in 2007. Similarly, the proportion of children covered by health insurance increased from 87 percent in 1990 to 89 percent in 2007 (see Table 1).

Progress has also been made in reducing the impact of environmental hazards, such as lead poisoning and unsafe drinking water, on child health over the past two decades. Lead poisoning can cause a multitude of health problems from learning disabilities and behavioral problems to seizures, coma, and death. Young children and children living below the poverty line in older housing are particularly at risk. Fortunately, blood lead levels have decreased in recent decades; for example, the percentage of young children (ages 1-5) with more than 10 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood dropped from 8.6 percent between 1988 and 1991 to 1.4 percent between 1999 and 2004.4 Access to safe drinking water is another important environmental measure of health since children are especially sensitive to certain contaminants in drinking water, which have the potential to cause illness, developmental disorders, and cancer. The positive news is that the percentage of children served by community water systems that did not meet all applicable health-based drinking water standards has dropped from 18 percent in 1993 to 6 percent in 2008, although estimates have fluctuated during that time period.

While there has been some progress in terms of child health over the past 20 years, trends in the area of childhood diseases offer a more mixed picture. The most common chronic disease among children is dental caries (cavities). And, the percentage of children (ages 5-17) with untreated cavities has declined from 24.3 percent in the late 1980s and early 1990s to 16.3 percent in more recent years. In contrast, the prevalence of asthma, another very common chronic childhood disease, increased in past decades (1980s and 1990s). More recent data show that in 2008, 9.5 percent of children (under 18) had asthma, an increase from 8.8 percent in 2001.

Asthma is a major cause of childhood disability and can be very burdensome in terms of both medical and indirect costs. For example, in 2003, 12.8 million school days were missed due to asthma among those who reported at least one asthma attack in the previous year.5 In addition, even after controlling for higher asthma prevalence, minority children have much greater rates of adverse outcomes, which include emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and death.6

Depression is another important medical condition with 8.3 percent of youth (ages 12-17) reporting at least one “major depressive episode” in the past year in 2008. Depression negatively impacts development and well-being of adolescents; however, not all youth are affected equally.7 For example, in 2008, female adolescents were almost three times as likely as males to have had a major depressive episode in the past year. The prevalence of this condition among all youth has not changed in recent years.

Most importantly, the rate of childhood obesity has increased significantly from the past. Child obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile for children of the same age and sex. In the second half of the 1970s, 5.5 percent of children (ages 2-19) were considered obese. This proportion increased to 17 percent of children in the most recent data available (2007-2008). When including overweight children (with a BMI between the 85th and 94th percentiles), this number nearly doubles to 32 percent.8 Childhood obesity has been associated with a variety of immediate and future health problems including high cholesterol and high blood pressure, both risk factors for cardiovascular disease, as well as asthma, diabetes, and psychological stress such as low self-esteem.

Researchers estimate that direct medical costs for children with elevated BMI are estimated to be $3 billion per year.9 In addition, many of the future health problems stem from the fact that obese children are more likely to become obese adults. And, obesity across all age groups is costly in terms of both direct medical costs and indirect costs that arise from losses in productivity, absenteeism, and premature death. Estimates suggest that obesity is responsible for almost 10 percent of total annual medical expenditures, or about $147 billion per year in 2008.10 Another study found that between 1987 and 2001, increases in the proportion of, and spending on, obese people relative to people of normal weight account for 27 percent of the rise in inflation-adjusted per capita spending.11 Conservative estimates find that the direct medical costs of obesity are similar in magnitude to those associated with smoking.12

Trends in Education

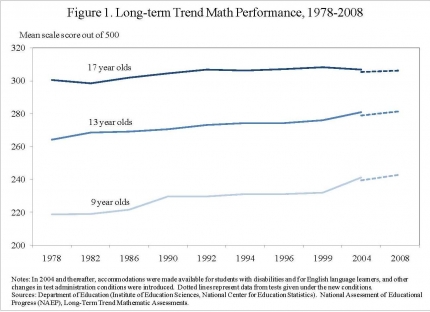

Along some dimensions U.S. student achievement has improved over the past 30 years, particularly as measured by the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP), the Nation’s Report Card. For example, as shown in Figure 1, the performance of 9-year-olds (who are typically enrolled in 4th grade) and 13-year-olds (typically 8th grade) improved in mathematics between 1978 and 2008. Nearly three-quarters of 13-year-olds in 2008 scored above the 1978 median, with similar gains throughout the distribution. The performance of 17-year-olds (typically 12th graders) has also improved, although the gain was smaller.

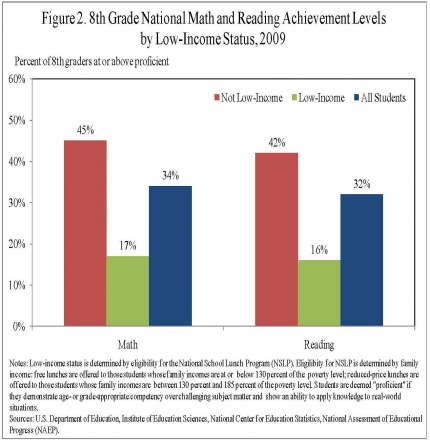

Despite this progress, the level of achievement is not nearly as impressive. In the most recent tests, only 32 percent of 8th graders were proficient in reading and only 34 percent in math, where a student is deemed “proficient” if he or she demonstrates age- or grade-appropriate competency over challenging subject matter and shows an ability to apply knowledge to real-world situations.13

This low level of attainment, which is observed at both the secondary and post-secondary levels, is underscored in international comparisons. Among the cohort born between 1943 and 1952 (that largely completed its education by the late 1970s), the U.S. has the highest percentage with at least a bachelor’s degree (or the equivalent) compared to other developed nations. However, that percentage has not grown in the U.S. while increasing substantially in other countries. The OECD data suggest that only 40 percent of Americans born between 1973 and 1982 have completed associate’s degrees or better which is lower than that in eleven other countries (led by Canada and Korea, where up to 56 percent completed some postsecondary degree or extended certificate program).14 High school graduation rates show a similar attern as the U.S. has slipped from the top to the middle in recent cohorts.

These relatively low rates of educational attainment have costs to both the individual and to society. As one example, individuals who have not graduated from high school earn less than those with a high school degree and are significantly less likely to be employed at a stable full-time job or one that pays benefits much less at all. As a result of their relatively poorer labor market prospects, these workers contribute less in taxes and are more likely to draw on public assistance. By one estimate, high school dropouts earn approximately $300,000 less over their lifetime than high school graduates (with no further education and in present discounted value terms) and contribute about $70,000 less in taxes.15

And so there is work to be done to strengthen the education and training of American workers and as we do so, it is important to emphasize that the task of improving later educational outcomes begins before elementary school. School readiness which involves both cognitive skills – as measured by vocabulary size, complexity of spoken language, and basic counting – and social and emotional skills – such as the ability to follow directions and self-regulate – is critical to later educational and labor market success. Children who arrive at kindergarten without these skills lack the foundation on which later learning will build. And yet relatively recent research indicates that as many as 45 percent of entering kindergarteners are ill-prepared to succeed in school.16 Because investments in the youngest members of U.S. society generate better-prepared students and healthier workers that earn higher wages, economists have estimated that the long-run benefits outweigh the costs of a high-quality pre-school. Steven W. Barnett and Leonard N. Masse estimate that a dollar investment in one program produced $2.50 in long-run savings for taxpayers.17 James Heckman, Nobel Laureate in Economics, and his colleagues estimated even higher savings of $7 from another program.18

The Impact of Family Circumstances on Child Well-Being and Implications for the Impact of the Recession on Children

A vast academic literature has attempted to explain the role of family economic resources on child well-being and has generally found that children from more advantaged families have better outcomes than those from less advantaged backgrounds. Children from wealthier families have higher educational attainment, are healthier, and are more likely to go on to have successful labor market outcomes than their poorer counterparts.

More specifically, studies have found that income is associated with a number of education-related outcomes such as a child’s cognitive abilities and school achievement. One study found that children in families with incomes below 50 percent of the poverty line scored significantly lower on a set of cognitive tests than children in families with incomes at 150-200 percent of the poverty line.19 Another study estimated that on average, children who had experienced poverty during some or all of their adolescence completed between 1.0 and 1.75 fewer years of schooling than children who had not.20 Similarly, proficiency rates on the NAEP assessments are much lower for those whose family incomes make them eligible for a free or reduced-price lunch, as shown in Figure 2. The low achievement in these subgroups is also reflected in low attainment as measured by high school completion, college enrollment, and college completion.

There is a similar relationship between family circumstances and health outcomes. For example, researchers in one study that controlled for maternal education and family structure found that children in families facing long-term poverty had more behavioral problems than children who had never dealt with poverty.21 In another, average blood lead levels were found to be 60 percent higher for children (ages 1-5) in lower-income families than for those in higher-income families.22 Similarly, poverty remains a significant factor in the prevalence of cavities with 26 percent of children in poverty having untreated cavities compared to just 11.8 percent of children with family incomes at or above 200 percent of the poverty threshold.

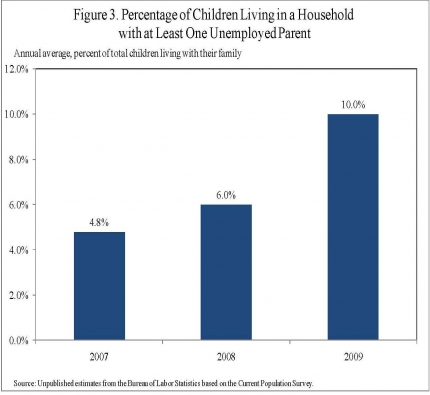

Given the relationship between family circumstances and child well-being, of great concern is the impact of the current recession on children. Since December 2007, total private employment decreased by 7.9 million, and the current unemployment rate remains unacceptably high at 9.5 percent. Children have also been adversely affected as the percentage of children living in a household with at least one unemployed parent more than doubled between 2007 and 2009 such that now 1 in 10 children live in a household with at least one unemployed adult (see Figure 3). Further, over two million homes were foreclosed in 2008 and the number of people in families that were homeless rose by 9 percent that year. According to one study, more than 450 school districts had an increase of at least 25 percent in the number of homeless students between the 2006-2007 and 2007-2008 school years.23 In the 2008-2009 school year, the U.S. Department of Education reported a 20 percent increase in the number of homeless students.24

While it is too early to know for certain the impact of this recession on children, by all expectations, it will set us back. Homeless children are, generally speaking, more likely to suffer from health and mental health problems and to perform poorly in school, than children in stable housing.25 Job loss not only affects the workers who lost their jobs, but also has a lasting impact on their children. In one important study, economists followed the lives of children whose fathers lost their jobs due to plant closings and those whose fathers had not been displaced. The researchers found that, as adults, the annual earnings of children whose fathers had been displaced were 9 percent lower than those whose fathers had not been displaced; they were also three percentage points more likely to ever receive public assistance.26

The recession also has had a negative impact on older youth: the unemployment rate for youth (ages 16-24) was 18.2 percent last month, nearly double the national unemployment rate. This weak labor market will likely adversely impact their future labor market outcomes as well. One study found that students who graduated during a recession experienced persistent lower wages than those who graduated during better times.27 Specifically, a 1 percentage point increase in the national unemployment rate decreased initial wages by 6 percent. Even ten years after graduation, the wage loss was still present at 4 percent. I note that this difficulty that young adults are having gaining exposure to the world of work, is one reason that the President has joined with Members of Congress to support funding for summer youth employment.

Given the current length of this recession, it is important to look not only at impacts of transitory poverty but also at the impact of longer-term poverty on child well-being. Persistent poverty status affects a plethora of outcomes, ranging from adult earnings to criminal behavior to health. Researchers estimate that the total difference in lifetime earnings between children who lived in persistent poverty and children who did not amounts to about 1.3 percent of 2008 GDP.28 Children living in poverty are more likely to be involved in criminal activity, which will cost society at least $170 billion annually. And due to the incidence of poor health in poorer children, direct expenditures on health care are estimated to cost an additional $22 billion a year.

While family income plays a big role in these adverse outcomes, there are also indirect channels through which the recession will affect children. For example, one study found that job loss is associated with increased divorce rates.29 Children in unstable families have poorer school performance and increased behavioral problems, and unemployment can also cause stress for parents, which can affect their behavior with their children.30 This, in turn, can affect children’s emotional adjustment.31

Finally, it is important to highlight one indicator of child well-being that, thanks to the Federal government, has not suffered during the recession -- health insurance coverage for children. Given that over one-half of Americans obtain their health insurance through their employer, hard economic times can bring increases in the numbers of children without health insurance coverage. Not surprisingly, the proportion of children covered by private health insurance has continued to decrease since the start of the recession. Fortunately, the increase in the proportion of children covered by public health insurance more than compensated for the decline in private insurance. According to the Census Bureau, about 10 percent of children were without health insurance in 2008. A more recent estimate from the National Health Interview Survey suggests that in 2009, 8.2 percent of children were without health insurance, the lowest level on record. These positive developments will continue as a result of the historic expansion of the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which extended coverage to 2.6 million additional children in fiscal year 2009, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, which will end limits on pre-existing conditions, extend the period of time during which children can stay on their parents’ health insurance, and make health insurance more affordable for all.

What Has to Change for Children to do Better?

Recognizing that my colleagues will speak about many of the Federal government’s efforts and several initiatives supported by the Administration, I would like to underscore four general areas that I believe are important for improving the well-being of children.

A Speedy Economic Recovery

First, given the importance of family circumstances on child well-being, an important short-run change is a solid and timely economic recovery. The CEA estimates that by the middle of the second quarter of 2010, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) had raised the level of real GDP by 2.7 to 3.2 percent and the level of employment by 2.5 to 3.6 million relative to what they would have been without it.32 However, unemployment remains at 9.5 percent, and recent economic data indicate that while a recovery is starting to take place, much stronger job gains are needed to put the millions of Americans who have lost their jobs since the start of this recession back to work. This is why the HIRE Act, the jobs tax credit that provides an incentive for small businesses to hire unemployed workers, is so important to this economy, as is extension of unemployment benefits. In addition, the President has continued to call for additional support for small businesses as well as for additional funding to help retain teachers as we head into the next school year. When parents have jobs that provide the resources to put nutritious food on the table and a safe and stable place to live, it is reflected in the well-being of their children.

A Commitment to Healthy Children

Second, with the alarming increase in childhood obesity and the associated health and economic consequences that ensue, it is important that we find a way to improve nutrition and healthy lifestyles among American children. A notable step is to expand and improve the Federal nutrition program. Two bills currently awaiting floor votes – the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act in the Senate and the Improving Nutrition for America’s Children Act in the House – aim to increase children’s access to healthier meals by providing additional funds to child nutrition programs, including the National School Lunch Program. The improved child nutrition program will not only assist schools in meeting meal requirements and enrolling eligible children but also support nutrition education in schools to promote healthy eating habits. In addition, the First Lady’s Let’s Move! campaign calls upon everyone who has an effect on children’s health (from parents to teachers to political leaders) to act together to end the epidemic of childhood obesity within a generation. To assist in achieving this goal, a White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity was established by the President and is implementing a series of 70 recommendations.

A Commitment to a World-Class Education

Third, the competitiveness of the U.S. economy depends on the productivity of its workers. A growing share of jobs requires workers with greater analytical and interactive skills, which are typically acquired with some post-secondary education. And yet students cannot succeed in post-secondary education and training programs if they are ill-prepared. While the current U.S. education and training system has been shown to provide valuable labor market skills to participants, it could be more effective at encouraging completion and responding to the needs of the labor market. As detailed in the CEA report, “Preparing the Workers of Today for the Jobs of Tomorrow,” a comprehensive strategy must include a solid early childhood, elementary, and secondary system that ensures students have strong basic skills; institutions and programs that have goals that are aligned and curricula that are cumulative; close collaboration between training providers and employers to ensure that curricula are aligned with workforce needs; flexible scheduling, appropriate curricula, and financial aid designed to meet the needs of students; and incentives for institutions and programs to continually improve and innovate; and accountability for results.33

The Federal government’s investments in these areas have moved in the right direction particularly with some of the innovative investments in the ARRA and the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. The Reauthorizations of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 and the Workforce Investment Act will enable the Federal government to continue these efforts so that the U.S. education and training system can once again be first in the world. The Administration also remains committed to working with Congress to make the Early Learning Challenge Fund a reality. This proposal, if enacted, would challenge States to establish model systems of early learning and ensure that more children enter school ready to learn and succeed.

Workplaces that Recognize Changes in Family Economic Structure

Finally, as documented in the CEA report, “Work-Life Balance and the Economics of Workplace Flexibility”, one of the biggest changes that impacts the lives of children is the growing participation of women in the labor force. For example, while in 1968, 48 percent of children were raised in households where the father worked full-time, the mother was not in the labor force, and the parents were married, by 2008, only 20 percent of children lived in such households. As a result, an increased proportion of children are raised in households in which all parents work in the labor market (for single-parent households, this means that the one parent works; for two-parent households, both parents work). In 1968, 25 percent of children lived in households in which all parents were working full-time; 40 years later, that percentage had nearly doubled.34

In addition, compared with 1965, in 2003 women spent more time on market work and significantly less time on nonmarket work such as food preparation, kitchen cleanup, and washing clothes. For men, the patterns were reversed as they spent substantially fewer hours on market work and somewhat more hours on nonmarket work.35 With men and women both performing nonmarket and market work, often one or both of them need the ability to attend to family responsibilities such as taking children to doctors’ appointments. And while many employers have adapted to the changing family circumstances of U.S. workers by providing flexibility in the work place (most commonly by allowing workers to periodically change when they work), many do not.

While the costs and benefits of adopting flexible work arrangements vary by employer, the benefits of adopting such management practices can outweigh the costs by reducing absenteeism, lowering turnover, improving the health of workers, and increasing productivity. As such, to the extent employers may not have accurate information about the costs and benefits of these practices and because benefits may extend beyond the individual employer and its workers, wider adoption of such policies and practices may well benefit firms, workers, and the U.S. economy as a whole, including children whose parents can more fully attend to their health care, schooling, and other needs.

Conclusion

While the well-being of children has improved along many dimensions over the past two to three decades, there is still work to be done especially in light of the recent economic recession. The Federal government has played, and must continue to play, a significant role in maintaining and accelerating progress through improved access to sound economic strategies that enable parents to provide for their children, quality health care, and high quality education from cradle to career. These investments are critical as our future prosperity depends on ensuring that American children from all backgrounds have the opportunity to become productive workers.

Thank you for your dedication to these issues and for holding this important hearing. I would be happy to address any questions that you may have.

1 The official poverty measure estimates poverty rates by comparing a household’s cash income to a threshold that accounts for family size and inflation. Noncash benefits, such as food stamps, are not included as income.

2 A household is defined as “food-insecure” if it was unable at times to acquire adequate food for active, healthy living for all household members due to insufficient money or other resources for food.

3 Annie E. Casey Foundation. 2010 KIDS COUNT Data Book: State Profiles of Child Well-Being. 2010.

4 Jones, Robert L., et al. “Trends in Blood Lead Levels and Blood Lead Testing Among U.S. Children Aged 1 to 5 Years, 1988-2004.” Pediatrics (March 2009): E376-85.

5 Akinbami, Lara J. “The State of Childhood Asthma, United States, 1980-2005.” Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, no. 381 (2006). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

6 Akinbami, Lara J., et al. “Status of Childhood Asthma in the United States, 1980-2007.” Pediatrics, American Academy of Pediatrics (March 2009): S131-45.

7 Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s Children in Brief: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. July 2010.

8 Ogden, Cynthia L., et al. “Prevalence of High Body Mass Index in U.S. Children and Adolescents, 2007-2008.” Journal of American Medical Assocation 303, no. 3 (2010): 242-49.

9 Trasande, Leonardo, and Samprit Chatterjee. “Corrigendum: The Impact of Obesity on Health Service Utilization and Costs in Childhood.” Obesity 17, no. 9 (2009): 1473.

10 Finkelstein, Eric A., et al. “Annual Medical Spending Attributable to Obesity: Payer- and Service-Specific Estimates.” Health Affairs (2009): W822-31.

11 Thorpe, Kenneth E., et al. “Trends: The Impact of Obesity on Rising Medical Spending.” Health Affairs (2004): W4-480-6.

12 Stein, Cynthia J., and Graham A. Colditz. “The Epidemic of Obesity.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (2004): 2522-25.

13 National Assessment of Educational Progress. “The Nation’s Report Card: Grade 8 National Math and Reading Achievement Levels.” 2009.

14 Organisation for Economic and Co-operation and Development. “Education at a Glance.” 2009.

15 The figures in the text have been inflated to 2009 dollars. Rouse, Cecilia E. “Consequences for the Labor Market.” In The Price We Pay: Economic and Social Consequences of Inadequate Education, edited by Clive Belfield & Henry M. Levin, pp. 99-124. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2007.

16 Hair, Eliabeth, et al. “Children’s School Readiness in the ECLS-K: Predictions to Academic, Health, and Social Outcomes in First Grade.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 21, no. 4 (2006): 431-54.

17 Barnett, W. Steven, and Leonard N. Masse. "Comparative Benefit-Cost Analysis of the Abecedarian Program and Its Policy Implications." Economics of Education Review 26, no. 1 (2007): 113-25.

18 Heckman, James J., et al. “The Rate of Return to the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program.” Mimeo, University of Chicago. April 2009.

19 Smith, Judith R., Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, and Pamela K. Klebanov. “The Consequences of Living in Poverty for Young Children’s Cognitive and Verbal Ability and Early School Achievement.” In Consequences of Growing Up Poor, edited by Greg J. Duncan and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, pp. 132-39. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1997.

20 Teachman, J.D., et al. “Poverty during Adolescence and Subsequent Educational Attainment.” In Consequences of Growing Up Poor, edited by Greg J. Duncan and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, pp. 382-418. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1997.

21 Duncan, Greg. J., Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, and Pamela K. Klebanov. “Economic Deprivation and Early-Childhood Development.” Child Development 65 (1994): 296-318.

22 Jones (2009).

23 Duffield, Barbara and Phillip Lovell. “The Economic Crisis Hits Home: The Unfolding Increase in Child & Youth Homelessness.” National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth (December 2008).

24 United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. “Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness.” 2010.

25 Duffield and Lovell (2008).

26 Oreopolous, Philip, Marianne Page, and Ann H. Stevens. “The Intergenerational Effects of Worker Displacement.” Working Paper 11587. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (August 2005).

27 Kahn, Lisa. “The Long-Term Labor Market Consequences of Graduating from College in a Bad Economy.” Mimeo, Yale University. August 2009.

28 Holzer, Harry J., et al. “The Economic Costs of Childhood Poverty in the United States.” Journal of Children and Poverty 14, no. 1 (2008): 41-61.

29 Charles, Kerwin K., and Melvin Stephens, Jr. “Job Displacement, Disability, and Divorce”. Working Paper 8578. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (November 2001).

30 Cavanagh, Shannon, and Aletha C. Huston. “Family Instability and Children’s Early Problem Behavior.” Social Forces 85, no. 1 (2006): 551-81; Morris, Pamela, Greg J. Duncan, and Christopher Rodrigues. “Does Money Really Matter? Estimating Impacts of Family Income on Children’s Achievement with Data from Random-Assignment Experiments.” Unpublished manuscript, Northwestern University (February 2004).

31 Kalil, Ariel. “Unemployment and job displacement: The impact on families and children.” Ivey Business Journal (July/August 2005).

32 Council of Economic Advisers. “The Economic Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Fourth Quarterly Report.” July 2010.

33 Council of Economic Advisers. “Preparing the Workers of Today for the Jobs of Tomorrow.” (July 2009).

34 Council of Economic Advisers. “Work-Life Balance and the Economics of Workplace Flexibility.” (March 2010).

35 See Table II in Aguiar, Mark, and Erik Hurst. “Measuring Trends in Leisure: The Allocation of Time Over Five Decades.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 122, no. 3 (2007): 969-1006.